Ramadan 2021: A time for Muslims to unite against Islamophobia

It has been more than a year since the Covid-19 pandemic first gripped the globe. Across Europe, we have watched states scramble to control the crisis after years of privatisation and divestment from the public health services that are so urgently needed.

We have been confronted with the realities of economic systems built for the profits of the few at the cost of the many, and of the direct impacts of a weakened welfare state. And yet, with all the senseless deaths, poverty and unemployment across Europe, the primary focus of our governments continues to be repressing and criminalising Muslims.

As we enter the holy month of Ramadan, during which millions of Muslims around the world practice fasting, the racist conspiracy theory that this will bring a spike in infections also follows us. The same Islamophobic narrative adopted by far-right groups and public figures last year has returned again, while their outrage over the lockdowns “stealing Christmas” seems to have vanished from the collective memory.

Despite the speed at which some of the racist accusations against Muslims are debunked, the damage is already done once such stories reach the public via social media

This has certainly been the rhetoric in the Netherlands. Despite Covid-19 infections remaining high, the country has been the last in the region to start vaccinating people. One would think that getting a handle on this would be a key priority for all political leaders. Instead, a few weeks after a national election driven by hate and division, the public discourse remains focused on Muslims as the problem.

Rotterdam Mayor Ahmed Aboutaleb responded to the extension of a national curfew, in place from 10pm to 4:30am, with concerns that it was coinciding with Ramadan. He stated that Muslims would want to visit their families during this time, suggesting that they would not respect the restrictions because they break their fast after sunset.

It is striking that politicians would portray iftar meals as super-spreader events, when members of the far right have been gathering in massive groups in recent months for demonstrations and electoral rallies. Similarly, when churches in right-wing bastions were filled to the rafters in the lead-up to Easter, the usual suspects were nowhere to be found.

The irony that these comments came from a figure celebrated for being the first big-city Muslim mayor in the country didn’t go unnoticed. But it seems the country is so racist that even when a Muslim reinforces a right-wing narrative, he is attacked for simply mentioning the M-word. Aboutaleb found himself on the receiving end of much far-right backlash for daring to suggest that the Dutch government should even factor in Muslims when making political decisions.

Disproportionate scrutiny

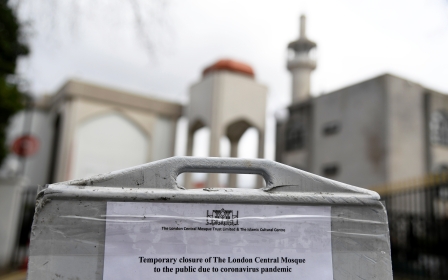

While there was no curfew in place this time last year, a national lockdown was in full swing, and the sense that disproportionate scrutiny would fall on Muslims was already strongly felt. Mosques did not fully reopen, even when Covid-19 restrictions eased last year. This is perhaps unsurprising, given that during the pandemic, the Dutch government’s scrutiny of Muslims did not cease. In fact, mosques found themselves facing stricter surveillance over their finances and “foreign” influences.

The climate of hatred recently intensified during the shockingly racist, anti-migrant, Islamophobic electoral period. The dance was led by the so-called Forum for Democracy, whose base peddles conspiratorial beliefs about oppressed groups being the source of infection - when they are not denying the pandemic entirely and fighting restrictions altogether.

At the same time, the Party for Freedom (PVV), led by Geert Wilders, which calls to ban mosques, Qurans and Islamic schools, won 17 seats in the national elections. The party has also called for the establishment of a ministry for “repatriation” and de-Islamification.

The issue, however, doesn’t stop at the Dutch borders. Last year, Muslims in the UK faced similar propaganda attacks from far-right groups and individuals. Videos circulated on social media of people praying in mosques, in an attempt to stoke hatred and accusations that Muslims and their institutions were not respecting lockdown rules. One clip of worshippers in Wembley Central Masjid supposedly praying despite restrictions made the rounds, until it was discovered that the mosque had been closed since January.

Curtailing civil liberties

Despite the speed at which some of the racist accusations against Muslims are debunked, the damage is already done once such stories reach the public via social media. The start of the pandemic was marked with the #CoronaJihad hashtag trending on Twitter; according to a report in Time magazine, around 300,000 such tweets were potentially viewed by millions of people in just a few days.

The flames of hatred have been lit, and there is a dangerous appetite for Islamophobia across Europe. The list just keeps growing, from Switzerland’s burqa ban, to France’s war against Muslims through so-called anti-separatism laws, to an alarming level of anti-Muslim attacks in Germany and a curtailing of civil liberties in Austria to supposedly combat extremism.

Alas, we enter Ramadan with even more uncertainties about our freedoms. But the last thing that our faith teaches us is despair.

We should not forget that the infrastructure of the war on terror - surveillance, Prevent and other so-called anti-radicalisation policies - was developed in Britain before being exported across Europe. That puts us in the UK in a position to lend support and resources to communities that are being criminalised and silenced in neighbouring countries. This, in turn, would strengthen our own national struggle.

It may sound simple, but there is no escape from oppressive and repressive conditions other than to organise in resistance. We have a month set aside for spiritual reflection and re-centring. We should use it to come together, strategise and build the broad fight that is so urgently needed.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].