Can Iran and Saudi Arabia bury the hatchet?

Iranian and Saudi officials have reportedly been holding talks in Baghdad this month to discuss outstanding issues between the two countries, including recent attacks by Yemen’s Houthi rebels against Saudi infrastructure. Iraq’s prime minister was instrumental in arranging the meeting, according to a report in the Financial Times.

As the news spread, the Saudis denied having held talks with Iran, as did outlets known to be close to Tehran. But Iran’s foreign ministry, while refusing to confirm or deny the reports, said that Iran welcomed talks with Saudi Arabia.

Both countries need to free themselves from their regional entanglements. But the extent to which Iran and Saudi Arabia can help each other is unclear

At this stage, it is difficult to predict whether substantial talks will take place between the two longstanding rivals - or even if they did, whether they would result in a significant reduction of bilateral and regional tensions.

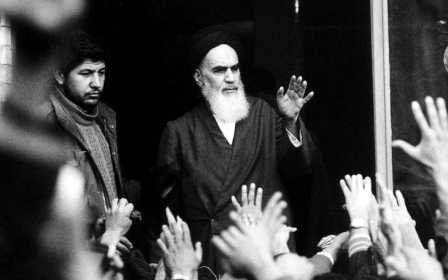

The Iran-Saudi conflict, ongoing since the 1979 Islamic Revolution, has been costly for both states and fuelled instability in a vast region, stretching from Afghanistan to Syria and Lebanon.

In Lebanon, it has been a factor in the recurring governmental crisis. In Syria, by backing rival factions, both states have contributed to prolonging the civil war.

Iraq has also suffered from this competition. Shortly after the 2003 US invasion, Saudi Arabia, Iran and other countries launched a fierce competition for influence there. They have organised and financed competing militia groups, which have challenged consecutive Iraqi governments and plunged the country into civil war. It is therefore not surprising that Iraq’s prime minister would have initiated the Tehran-Riyadh dialogue. A compromise between the two could vastly improve Iraq’s security environment.

Guarded optimism

Indeed, a successful Saudi-Iran dialogue could help to resolve a variety of Middle Eastern conflicts. But it is important to note that most of these conflicts also have internal causes, and have been affected by other interstate rivalries. In Iraq, Turkey and the UAE are major actors, and Turkey is deeply engaged in Syria. The UAE is also a key actor in Yemen.

It is thus unlikely that a successful Saudi-Iranian dialogue and compromise would, on its own, quickly end the current conflicts. Still, it could reduce their intensity and improve the prospects of resolution.

Several factors warrant guarded optimism about the prospects of a Saudi-Iranian dialogue. Firstly, both Tehran and Riyadh have failed to achieve their regional ambitions, reaching a stalemate in most arenas. The most significant and costly setback for Saudi Arabia has been Yemen. Riyadh expected a quick victory that would have cemented its leadership in the Middle East. Instead, it is bogged down in an unwinnable war, fuelled by Iran’s support for the Houthis.

Meanwhile, Iran has suffered setbacks in Iraq and Syria. While Tehran still enjoys considerable influence in Baghdad, many Iraqis have grown resentful of what they see as its interference, in addition to the country becoming an arena for US-Iran confrontation. They don’t want to depend too much on Iran, hoping for balanced relations with Tehran and major Arab capitals.

Biden push

In Syria, Russia is trying to force out Iran after using its human and economic resources to buttress the Assad regime. Iran’s regional adventures have also made it the subject of unprecedented US sanctions, which have choked its economy. Iran no longer has the financial resources to continue its past strategies.

In short, both countries need to free themselves from their regional entanglements. But the extent to which Iran and Saudi Arabia can help each other is unclear. Iran cannot simply force the Houthis to agree to a compromise against their interests, and Saudi Arabia cannot protect Iran against its local adversaries. But if both sides discourage their allies and proxies from acting against the other, the chances for resolving current conflicts would increase.

Secondly and more importantly, US global and regional priorities have been shifting under the Biden administration. Facing challenges from China and Russia, the US is reassessing the global distribution of its military assets and rethinking its overall strategy.

US President Joe Biden’s decision to withdraw American troops from Afghanistan by 11 September 2021 reflects this mindset. Whenever safe, the US would also like to reduce its military presence in Iraq and the Gulf. This could be one reason for the Biden administration’s desire to reduce tensions with Iran through the new, indirect round of talks over the nuclear deal.

The US also appears to be moving away from its past, unquestioned support for Saudi Arabia. Without this blanket support, Riyadh would have to curtail its regional ambitions and reach compromises with competitors.

The Israel factor

Israel, meanwhile, would be unhappy about a possible Iran-Saudi Arabia detente. For decades, Israel has used the Iran threat to improve its own relations with the Gulf Arab states, with some success; it now has diplomatic relations with Bahrain and the UAE.

But Saudi Arabia has thus far refrained from establishing diplomatic ties with Israel. With less hostile Iran-Saudi ties, Israel would lose a bargaining chip in trying to cement its relations with the Gulf states. Yet, in view of changing US priorities, including a desire to revive the nuclear deal, Riyadh might judge that it would be better to reach a modus vivendi with Tehran and not rely too much on ties, even informal ones, with Israel.

Given the deep-rooted differences between Riyadh and Tehran, starting a dialogue and reaching an understanding is a difficult prospect. And even with some form of Saudi-Iran compromise, the Middle East’s problems would not miraculously disappear. But it could certainly improve the chances of limiting or resolving ongoing conflicts.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].