How the world’s oldest masks tell a story of Palestinian dispossession

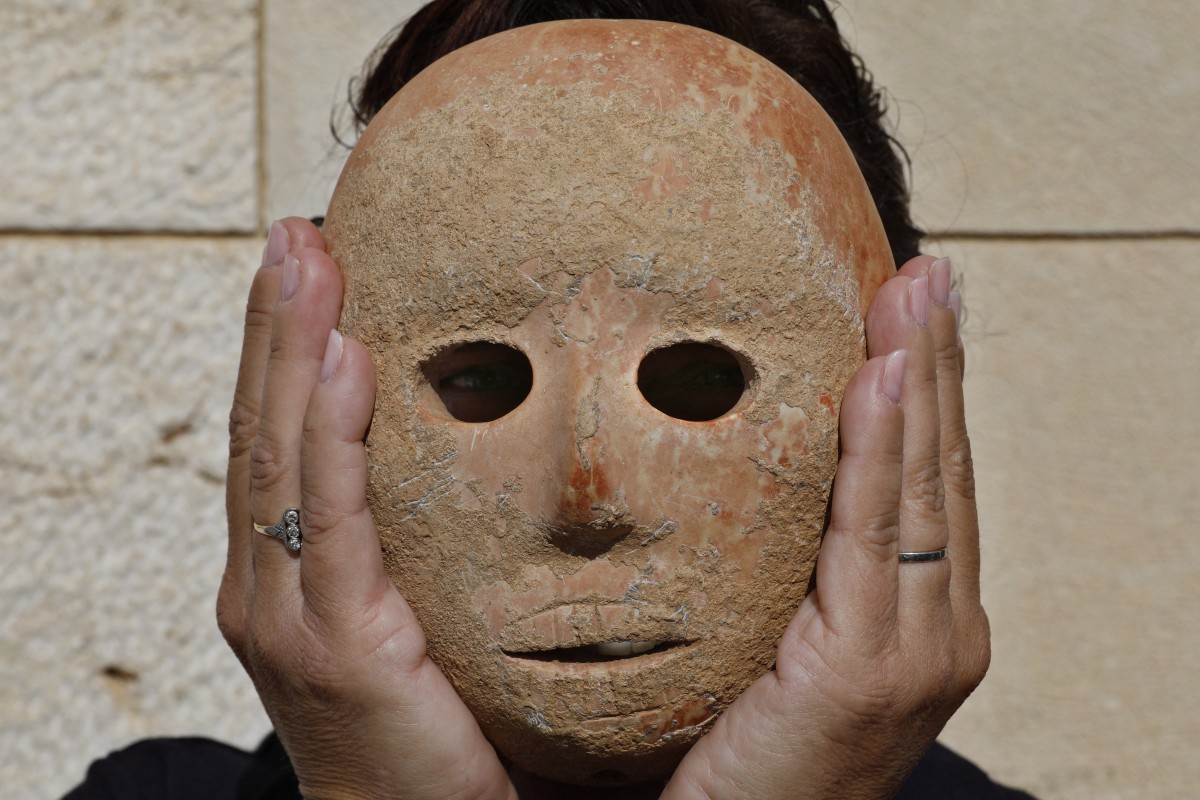

When a British missionary rode through al-Ram in 1881 asking for antiquities, residents of the Palestinian village tried to stop him from taking the local treasures. Armed with guns, a group of men confronted him and refused to let him take the village’s ancient stone mask. At least, this is how the story was reported by Thomas Chaplin, the British man who took the mask.

“A woman brought me a very curious stone mask, which I immediately purchased for a small sum,” wrote Chaplin, who was then the director of the evangelical London Society for Promoting Christianity Amongst the Jews’ hospital in Jerusalem.

“It seemed, however, that the object was regarded in the village as a sort of talisman which it would not be well to part with, so a number of men ran after me with their guns and demanded it back,” he continued in an article published in the Palestine Exploration Fund Quarterly Statement nine years after the incident. The villagers’ attempts to hold on to the mask, however, were not successful.

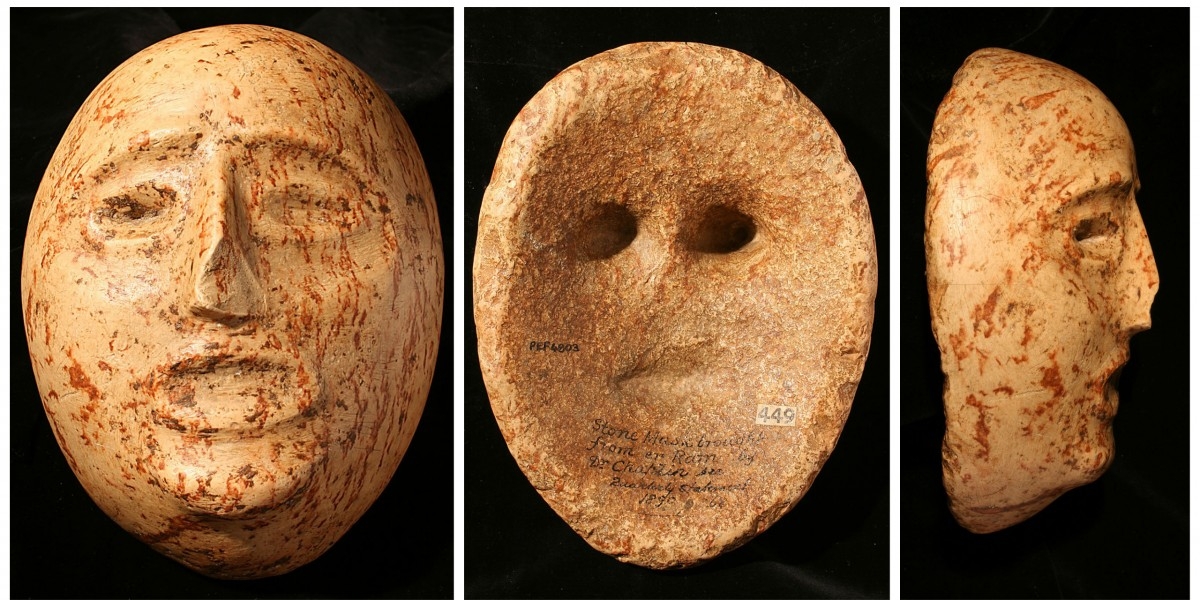

Today the mask is believed to be one of the oldest known in the world, and it is part of the Palestine Exploration Fund’s (PEF) archaeological collection, a British society based in London.

“It’s a fascinating object, we believe it comes from the ritual material culture of the Neolithic period, about nine to 10,000 years ago,” says Felicity Cobbing, PEF’s chief executive. Since Thomas Chaplin was an associate of the PEF who often provided the organisation with assistance, it is likely the mask was donated to the fund after his death.

Established in 1865 under the royal patronage of Queen Victoria, the PEF’s collection in London includes thousands of artefacts taken from Palestine between the 1860s and the 1930s.

“The mask was acquired in an open transaction,” says Cobbing, who adds that by taking the mask to England, Chaplin didn’t break the terms of the Ottoman Antiquities Law, which allowed the export of portable artefacts.

“According to the circumstances of the time it was not unusual and not illegal,” she tells MEE. “He [Chaplin] paid for it, and eventually they [the villagers] agreed to the sale.”

Not everyone, however, is convinced of the legitimacy and fairness of the purchase.

“It has to be returned,” says Tawfiq Abu Hammad, who lives in al-Ram. Abu Hammad, who works as an accountant at the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees (UNRWA), believes the mask was taken under duress.

For the resident of al-Ram, the appropriation of antiquities in the late 19th century is only an episode in the long history of systematic dispossession of Palestinians by colonial powers. Those in power might have changed, but he says deprivation is ongoing.

“Now the biggest hardship in al-Ram is the wall and the continuous theft of land,” says Abu Hammad. Al-Ram lies northeast of Jerusalem, and is now a town surrounded on three sides by the separation wall built by Israel. Since it was occupied by Israel in 1967, at least one hundred hectares of the town’s land have been confiscated to build Jewish settlements and Israeli military bases.

For Cobbing, the question of restitution is part of a larger debate around decolonisation. “We are trying to be honest about our colonial roots and colonial past, and how our work was used within colonial agendas whether that was our intention or not,” she says.

PEF’s chief executive says the organisation is reflecting on the role it played in collecting data that served British interests in Palestine before the establishment of the Mandate, and by making information, resources and grants available to everyone. The return of objects, she says, is “a complicated issue” and needs to be taken on a case-by-case basis.

Controversial treasures

Although the mask from al-Ram is very rare and immensely valuable, it is not unique. There are 15 other masks which were found in the West Bank and near the Dead Sea, and are believed to date from the same period.

"These masks also refer to some beliefs and practices of people in the Stone Age," says Mohammad Jaradat, director of Antiquities in Jericho. "Especially that these masks were worn to perform religious rituals and during the burial operations of the dead, who were buried inside their homes."

"For Palestinians, these historical objects are evocative. They act as vessels carrying our memories and traumas (...) these tactile forms are not merely material objects - they are tools that we identify with and resist with, and with which we exert our disappearing existence.

"For Palestinians, they are emotional companions, " says Dima Srouji, a Palestinian architect who teaches at Birzeit university, in an article about how Israel is displacing artefacts from the occupied West Bank and erasing Palestinian identity.

Scattered around the globe, the oldest known masks are now stored in collections in New York, London and Paris, and at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem, and so are inaccessible to the majority of Palestinians from the areas where the masks came from, since Palestinians from the West Bank can only enter Israel with a military permit.

The owner of the largest private collection of Neolithic masks taken from the West Bank is the hedgefund billionaire Michael Steinhardt, who has eight masks in his home in New York on display next to Picasso paintings. Steinhardt, who is also the co-founder of Taglit-Birthright Israel, an organisation that sponsors free trips to Israel for young adults of Jewish heritage, has been collecting art and antiquities for several decades.

His collection has come under scrutiny in recent years. In 2017, a marble torso that had been stolen from Sidon during the Lebanese civil war was found in his Manhattan apartment and returned to Lebanon. A year later, nine works were seized from his home by authorities who said the objects had been looted from Greece and Italy.

Many of the artefacts were stored in former Israeli Defence Minister Moshe Dayan's garden, which became one of the largest private antiquities collections in Israel

The Israel Museum owns two masks and a mask fragment. One of them was found by a team of archaeologists in 1983 in a cave at Nahal Hemar, near the Dead Sea. The other one was taken from the West Bank in 1970 by Moshe Dayan, who was Israel’s minister of defence at the time.

Before becoming a minister, Dayan served as commander-in-chief of the Israeli army. His name is still inscribed on the inside of the Neolithic mask, which was reportedly found by a farmer on the outskirts of the Palestinian village of al-Hadeb, where Neolithic remains have been discovered.

Dayan wrote that he bought the mask from an antiquities dealer near Hebron, and that the labourer who unearthed the mask only asked for a licence to drive a tractor as compensation.

According to Israeli archaeologist Raz Kletter, the general often used his position and authority to collect artefacts illegally. He says that some Palestinians were so intimidated by the powerful general that if they had artefacts for sale, they would only charge him a fraction of the market value.

“Dayan used army resources, even helicopters, to appropriate archaeological finds,” Kletter tells MEE. The military leader had no licence and no formal training as an archaeologist but he would often dig for his own private collection in occupied territory, from the Sinai and the Golan Heights to the West Bank and Gaza.

Many of the artefacts were stored in Dayan’s garden, which became one of the largest private antiquities collections in Israel.

When Dayan died in 1981, his widow sold his collection for $1m to the Israel Museum, which acquired it through a donor. The sale was widely criticised, as according to Kletter and other archaeologists, many of the 1,000 objects in his collection were acquired illegally (although his wife said that Dayan had legally purchased the bulk of the collection).

In 2014, the two masks owned by the Israel Museum were exhibited together in Jerusalem with other masks from Michael Steinhardt’s private collections for the first time.

“This is a family reunion of the oldest surviving portraits of ancient man,” Debby Hershman, the Israel Museum curator who organised the exhibition and conducted research on the masks for a decade told the Israeli newspaper Haaretz. “We are bringing them back home,” she added.

But it wasn’t exactly “home”. Although the Israel Museum was built in the early 1960s on the lands of the Palestinian village of Sheikh Badr and was designed to resemble an Arab village on the hill over Jerusalem, most Palestinians are not allowed to visit it.

The majority of the residents of the areas where most of the masks were found and taken from - Palestinian towns and villages such as al-Ram, al-Hadeb, and the Hebron Hills - were unable to see the masks the only time they were on public display because of the restrictions placed on Palestinians entering Jerusalem.

Reclaiming the masks

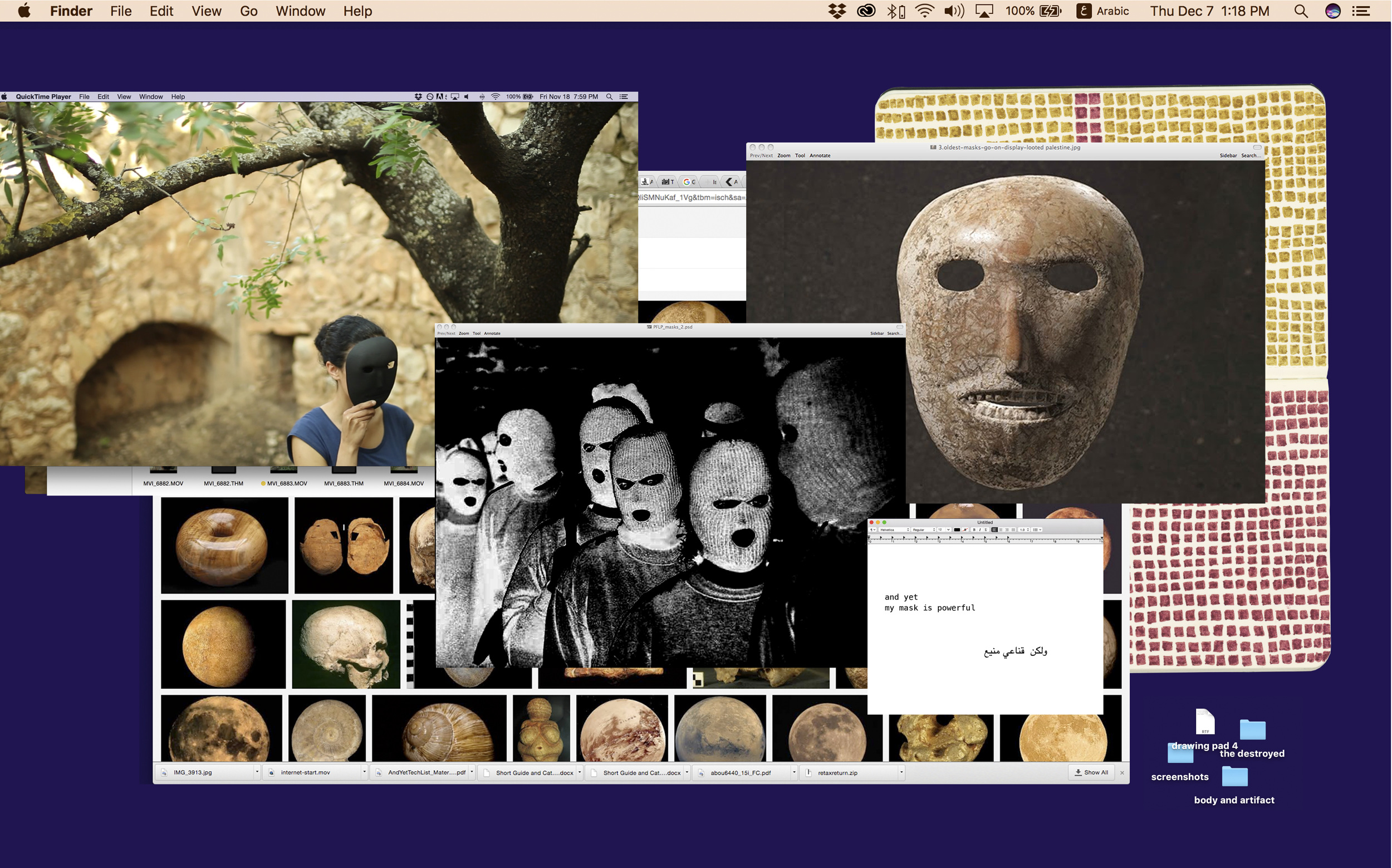

The artists Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme were among those who weren’t able to easily access the exhibition. In 2014, they came across the Neolithic masks online while doing research for their work.

“We always had a fascination with masks and with anonymity, with being anonymous as a political act,” says Basel Abbas. When they googled “masks + Palestine”, they were expecting to find images of Palestinians wearing ski masks at protests, but photos of the ancient masks exhibited at the Israel Museum also showed up in the results.

'These masks don’t just pre-date Palestine and Israel, they pre-date all religions'

- Basel Abbas, artist

“We were interested in how the museum was narrating these masks,” Abbas tells MEE. The exhibition referred to them as “our masks” from “the ancient Land of Israel”. In the exhibition’s catalogue, the borders of the West Bank are erased and only terms like “Judean Hills” and “Judean desert” are used, rendering Palestinians invisible.

“These masks don’t just pre-date Palestine and Israel, they pre-date all religions. So for a single entity to try to claim this as part of their national narrative is just taking mythology to a whole new level,” says Abbas. “We started to think about how to produce counter-mythologies, how to intervene.”

The museum made a virtual tour available online, which made it possible for the artists to replicate the masks on display, despite not being able to visit the exhibition.

“We decided to reproduce the masks and break [their] aura, to make multiple copies. We worked with a 3D designer, zoomed in on all the angles and created the masks in different materials,” Abbas tells MEE.

After hacking the online exhibition and making 3D copies of the masks, the artists started making trips to the sites of Palestinian villages destroyed in 1948 when the state of Israel was established.

Young Palestinians would wear the masks at the sites, and create new rituals for the masks that 9,000 years ago were likely associated with ancestor worship.

The masks and the destroyed villages became two key elements in a project the artists named And Yet My Mask Is Powerful, a verse taken from Adrienne Rich’s poem Diving into the Wreck, which describes a scuba-dive to a site of wreckage.

“[The poem] gave us the language to start to think about the wreck not as a site of ruin, but as a site of potential,” explains Abbas. “So it helped us think about the destruction of the villages inside what is today Israel, the heart of the destruction and erasure of Palestinian communities.”

According to the artists, by returning to the sites of destruction, Palestinians are activating the spaces and therefore refusing to accept their erasure and reclaiming them as living spaces.

“In colonial time, there is an attempt to relegate things to the past, as belonging to history and to museums,” says Abbas. “But indigenous people are essentially saying: we want to use this, this belongs to us, so it becomes a battle over time, over living time.”

First presented in 2016, the multi-part project has been exhibited across the world, from the Palestinian Museum in Ramallah to museums and galleries in Europe, the US and the Middle East. It has also been published as an artist book by Printed Matter, an arts organisation based in the US.

The project includes a five-channel video projection and a mixed-media installation with the 3D-printed masks placed next to vegetation collected from the sites of destroyed Palestinian villages. Abbas says it’s a long-term project they will continue to work on and that new parts are upcoming.

What the artists are trying to show is that while it can be traced back to the 19th century, the appropriation of the masks by Europeans and Israelis - from missionaries to army generals - is not something that is in the past, since Palestinians continue to be dispossessed of their material culture.

In 2018, an Israeli settler found a mask believed to be from the same period in the southwest of Hebron, in the occupied West Bank. Even though it’s against international law to remove cultural property from occupied territories, the mask was taken by Israel’s Antiquities Authority.

"We have documented only what Israel confiscated following the occupation of the West Bank in 1967," says Muhannad Sayel, director of the national registry at the Palestinian Ministry of Antiquities. "We have documented 20,311 artefacts [...] We are seeking to present a file to the International Criminal Court on this issue to demand the restoration of antiquities seized by Israel, and we are now at the stage of preparing this file."

MEE reached out to the Israel Antiquities Authority for comment but had not received one at time of publication.

The Israeli government maintains it is within its right to oversee archaeology in the areas it controls in the West Bank. The military has its own archaeological unit, which claims it is its responsibility to oversee excavations and “protect” archaeological sites from illegal digging and the smuggling of artefacts.

For the artists, the fact that Israeli authorities took the mask in 2018 just shows how current their work still is, and why they will continue working on the topic.

“The looting of Africa, the Middle East and Asia by Europe is ongoing, and this is part of that framework, a continuation of that mindset,” says Abbas. “Looting, whether it’s for material wealth and natural resources, or history and ownership over narratives, [is] an extension of what’s happening in Palestine today.”

Additional reporting by Shatha Hammad

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].