'Epic Iran' exhibition launches in London despite sanctions setbacks

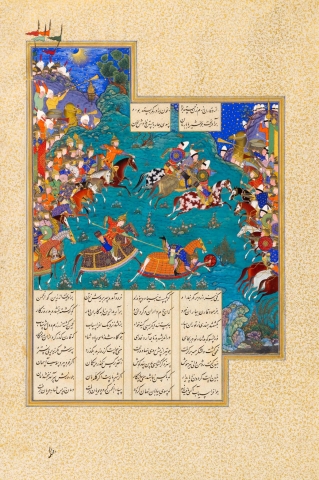

Epic Iran is described by London's Victoria and Albert Museum as the first UK show in nearly a century to take on “an overarching narrative” spanning 5,000 years of Iranian art, design and culture. It ranges from ancient treasures to leaves of illuminated manuscripts of the Shahnameh, or Book of Kings, to Iranian modern and contemporary art.

But continuing sanctions and global events - since the Covid crisis broke in March 2020 - mean that Epic Iran will have no loans from Iran itself of precious objects to show London audiences, organisers have confirmed.

Additional items borrowed from institutions ranging from the New York’s Metropolitan Museum to the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford will more than make up the gap, they say. More than 30 national and international collections have lent items to the show.

In 1931, London's Royal Academy hosted the International Exhibition of Persian Art, with 2,000 exhibits from collections worldwide, with King George VI and Reza Shah Pahlavi as its patrons. The entrance was a recreation of an Isfahan mosque; the opening was marked by a special supplement in The Times. An array of Eastern splendours included items loaned from the Golestan Museum in Tehran and the Shah's own collection.

With Covid rules finally eased to allow the reopening of UK museums, the V&A show now promises to conjure up an Isfahan dome using ten-metre-long paintings replicating tile-work patterns. Ten sections and an “immersive design” will transport visitors to an Iranian city with gardens, palace, and a library, the museum says.

The exhibition is split into sections including the Persian Empire of Cyrus the Great, with the famous Cyrus Cylinder on loan from the British Museum, hailing him as ruler of Babylon. Other sections examine the role of Islam, and the importance of Persian literature.

But among 300 precious objects carefully culled from major institutions, from the Louvre to the Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg, nothing has travelled from Iran itself.

Around a dozen ancient treasures including silver and gold from the National Museum of Iran are shown in the hefty £40 catalogue for Epic Iran, a show the V&A director Tristram Hunt says will “honour Iran’s epic cultural story”. But the Iranian museum in the end could only provide photographs, not the objects themselves.

A V&A spokeswoman told MEE that “logistical arrangements did not make it possible to borrow objects from Iran”.

With the British-Iranian aid worker Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe just sentenced to a further year in jail, the tense relations and complicated historical legacy between Britain and Iran are still playing out. But that played no role in the loans issue, the V&A insisted.

The decision to forgo Iranian loans was taken early in 2020 as “the travel of objects outside of Iran became increasingly difficult logistically,” a museum spokesperson said. The V&A had explored a loan exchange with Iran but “rising costs, global events and a growing backdrop of uncertainty” ruled it out.

Iran has made major loans to other European countries including to The Rose Empire, a show at the Louvre-Lens Museum in France on the Qajar period, in 2018. The British Museum received loans from Iran for its shows Forgotten Empire, the World of Ancient Persia, in 2005, and Shah Abbas: The Remaking of Iran, in 2009.

But in the last two years, since US President Donald Trump withdrew from the Iran nuclear deal and reimposed sanctions, “no institutions have managed to borrow stuff from Iran”, said John Curtis, co-curator of Epic Iran, academic director of the Iran Heritage Foundation, and the former head of the Middle East Department at the British Museum.

Sanctions have made money transfers for insurance or shipping fees hugely difficult. Shipping conditions have been so challenging that no contemporary works have come over from Iran either. “Insurance companies can’t provide insurance because of sanctions, for shipping or sending anything to Iran, it wouldn’t be possible,” says Curtis.

Forgotten Empire

Curtis said there was a huge appetite in Britain for understanding Iranian culture. When Forgotten Empire opened at the British Museum in 2005, there were queues around the block.

“I think people do want to be informed about Iran,” Curtis said. “Iran is so much in the news, all of it negative, people I am sure suspect there is a more positive side and want to know it, and this is what this exhibition is going to tell them.”

Curtis’s personal highlights from Epic Iran include a gold rhyton, a pouring vessel used like a drinking horn, shaped like a winged lion, dated from 500-330 BC from the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

“It’s a good example of the luxurious lifestyle enjoyed by the elite in the Persian Empire period,” he said. “A lot of very fine work is involved in it, it is a triumph of the goldsmith’s art.”

A gold armlet, from the Oxus Treasure, in the Victoria and Albert Museum’s own Iranian collections, is one of around a dozen exhibits in Epic Iran that also appeared in the 1931 exhibition. So is a 16th Century carpet showing scenes with human figures and beasts and birds owned by the Duke of Buccleuch, one of Britain’s biggest aristocratic families.

From the Sarikhani Collection, an extraordinary new collection rapidly assembled by an Iranian family in Oxfordshire, there is a page from the famous Shahnameh of Shah Tahmasp, a version of the Persian Book of Kings that is one of the most famous illustrated manuscripts in history, made in Tabriz in 1523-35.

Modern works in the show include The Poet and the Beloved of the King, by the Iranian artist and sculptor Parviz Tanavoli, the best-known artist of his generation in Iran. Another is an untitled work by Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian, a pioneering figure of Iranian modern art who died in 2019 and has a museum dedicated to her in Tehran.

Early reports suggested the V&A was seeking as many as 40 loans from Iran, particularly early artefacts. Proposed Iranian loans included a gold beaker at least 3,000 years old, embossed with horned animals, and a gold face mask 2,500 years old.

High-profile museum loans have always been the stuff of cultural diplomacy. The former director of the British Museum, Neil MacGregor, recalled making three visits to Iran in the 2000s as the institution sought loans for exhibitions. There was speculation in the Iranian press at the time that Britain would either keep the artefacts, or even send back fakes instead.

The “uniquely complex” relationship between Britain and Iran, reaching back to the 19th Century and including the toppling of Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh by British and American intelligence services in 1953, meant that “on the Iranian government side there is a difficulty to trust Britain completely”, MacGregor said.

But this time, Curtis stressed, “there wasn’t any unwillingness on the Iranian part at all. If it had been possible they would have liked to send them. It just came to a point where it wasn’t possible. It’s unfortunate but in the circumstances hardly surprising.”

In a foreword to the catalogue for Epic Iran, opening on 29 May, V&A director Hunt notes that the exhibition comes at a time when “western audiences are too often offered just one narrative” of Iran.

“For many, Iran’s monumental artistic achievements still remain surprisingly unknown and its importance as a distinctive civilisation often obscured,” Hunt writes.

“We want to help those in Britain and beyond to learn about the incredible art and design from one of the world’s greatest historic civilisations.”

Epic Iran will run at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London from 29 May - 12 September 2021

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].