Sheikh Jarrah explained: The past and present of East Jerusalem neighbourhood

Sheikh Jarrah, the Palestinian neighbourhood in occupied East Jerusalem facing imminent Israeli eviction, was once a breezy orchard lying less than a kilometre north of the ancient walls of Jerusalem’s Old City.

In the early 20th century, wealthy Palestinian families moved to build modern houses in the area, escaping the narrow streets and the hustle and bustle of their air-tight homes in the Old City.

The neighbourhood's name refers to the personal physician of the Islamic general Saladin, who is believed to have settled there when Muslim armies captured the city from Christian crusaders in 1187.

Refugees from Palestine 1948

In 1956, 28 Palestinian families settled in the neighbourhood. Those families were part of a wider population of 750,000 forcibly expelled by Zionist militias during the 1948 war - known to Palestinians as the Nakba, or "catastrophe" - from the Arab towns and cities that became Israel.

East Jerusalem was administered by the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, which governed the West Bank. Jordan had built houses for the 28 Palestinian families in 1956 with the approval of the UN agency for Palestinian refugees, UNRWA.

In the 1960s, the families agreed a deal with the Jordanian government that would make them the owners of the land and houses, receiving official land deeds signed in their names after three years. In return, they would renounce their refugee status.

However, the deal was cut short as Israel captured and illegally occupied the West Bank and East Jerusalem in the 1967 Middle East war and Jordan lost control of the territories.

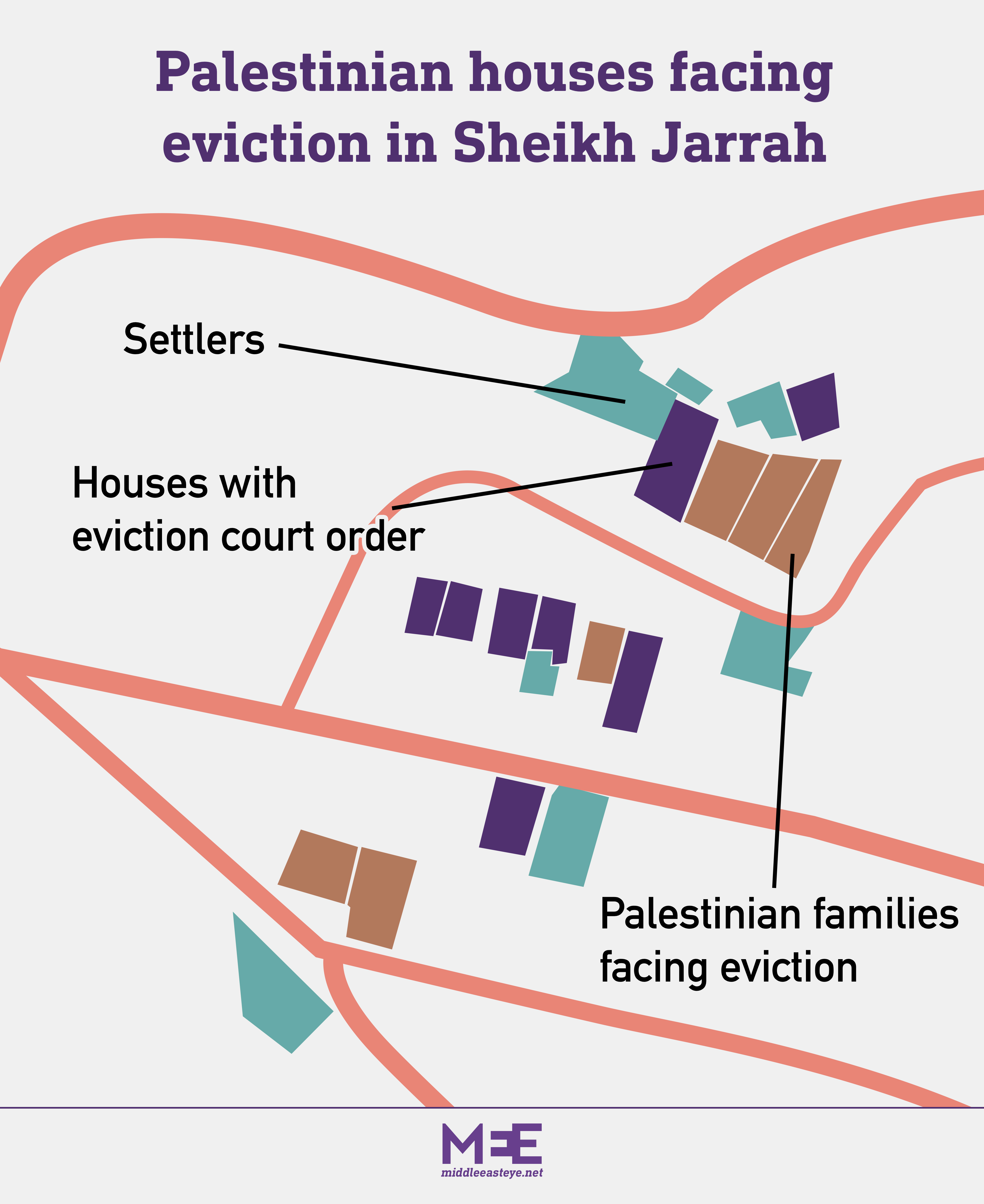

Currently, there are 38 Palestinian families living in Sheikh Jarrah, four of them facing imminent eviction, while three are expected to be removed on 1 August.

The rest are in different stages of court cases, going head-to-head with powerful Israeli settler groups in Israeli courts.

Jerusalem's 'Holy Basin'

Since Israel seized East Jerusalem in the 1967 war, Israeli settler organisations have claimed ownership of the land in Sheikh Jarrah and have filed multiple successful lawsuits to evict Palestinians from the neighbourhood.

Two settler groups filed lawsuits saying that Sephardic Jews owned the land in 1885, during Ottoman rule, which ended in 1917.

Israelis have made similar claims to owning Palestinian lands that lie less than a kilometre away from the Old City of Jerusalem.

Israel has a grand settlement strategy called the "Holy Basin," which is a set of settler units and a string of parks themed after biblical places and figures around the Old City of Jerusalem. The plan requires the removal of Palestinian houses in the area.

In November, an Israeli court ratified the eviction of 87 Palestinians from the Batan al-Hawa area in Silwan, south of Al-Aqsa mosque, in favour of the Israeli settler group Ateret Cohanim.

This group, which aims to expand the presence of settlers inside Palestinian neighbourhoods of East Jerusalem and around and inside the Old City, had sued the residents of Batan al-Hawa, claiming that the land was owned by Yemeni Jews during the Ottoman period until 1938, when the British Mandate moved them due to political tensions.

Israeli law works in favour of settlers by allowing only Jews to claim property they claim they have owned prior to 1948 while denying the same right to Palestinians.

Owners turned tenants

On Sunday, Israel’s Supreme Court ordered that the Iskafi, Kurd, Jaanoi and Qassem families - consisting of 30 adults and 10 children - evacuate their homes by 6 May. These families have been shunted around the courts for almost four years.

The court gave the Hammad, Dagani and Daoudi families living in the same area until 1 August to evacuate.

In 1982, Israeli settler groups asked the court to evict 24 Palestinian families living in Shiekh Jarrah. In 1991, the families faced another twist when they accused their Israeli lawyer and legal representative of forging their signatures on documents in 1991 stating that the ownership of the lands belonged to the settlers.

Since then, Palestinian residents of Sheikh Jarrah had been treated as tenants in front of the Israel courts, facing removal orders to allow the way for settlers to take over their houses.

In 2005, the Israeli court dismissed Ottoman documents presented by Suleiman Darwish Hijazi, one of the residents of Sheikh Jarrah, as evidence of his ownership of the land.

In 2002, 43 Palestinians were evicted from the area and Israeli settlers took over their properties. In 2008, the al-Kurd family was removed, and in 2009, the Hanoun and Ghawi families were evicted and in 2017 the Shamasneh family was also removed from their home by Israeli settlers.

Palestinians had called for Jordan to release official papers and documents to prove their ownership. In April, Jordanian Minister of Foreign Affairs Ayman Safadi handed over documents proving Palestinian ownership of their properties in Sheikh Jarrah, in a bid to prevent a new mass eviction.

Last week, the Jordanian government ratified 14 agreement from the 1960s with Palestinian families in Shiekh Jarrah to strengthen their position against Israeli courts.

Since the beginning of 2020, Israeli courts have ordered the eviction of 13 Palestinian families in Sheikh Jarrah.

The area became a focal point of protest and sit in solidarity activities, drawing in Palestinian and anti-occupation Israeli and international activists.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].