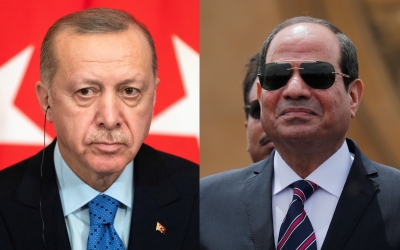

A Turkey-Egypt detente could begin to reduce tensions in the region

After being at loggerheads for much of the past decade, Turkey and Egypt have slowly and carefully developed a path towards cooperation in recent months, cognisant of the delicate environment for potential bilateral normalisation.

Earlier this month, the first solid diplomatic talks since 2013 took place in Cairo between the Turkish and Egyptian deputy foreign ministers. Both countries released coordinated statements that were modest, carefully crafted and offered a ray of optimism. The talks were framed as “exploratory discussions”, despite plenty of behind-the-scenes meetings between state officials over the past year.

A wide range of serious issues is at stake, in particular the Libya conflict, maritime disputes in the Eastern Mediterranean, and the Muslim Brotherhood’s presence in Turkey. For Egypt, Libya is a central issue after Turkey became a game-changer in the country, managing to turn the tide in favour of the UN-recognised Government of National Accord (GNA), which had been cornered in 2019 by warlord Khalifa Haftar’s powerful militia. Haftar is backed by Russia, Egypt and the UAE.

Both countries had compelling reasons not to leave the table, with serious regional threats dictating new foreign policy orientations and revived alliances

Ankara has invested substantially in Libya to prevent an economic collapse during the peak of the conflict. The GNA has since emerged as a reliable power in total control of Tripoli, leading to the formation of a national unity government headed by Abdul Hamid Dbeibeh, a staunch ally of Ankara, to lead the war-torn country towards long-delayed elections this December.

Cairo’s institutional apparatus already shares some common ground with Ankara on the Eastern Mediterranean file, as aligning with Turkey - and now Libya - could afford Egypt a larger share of waters than Greece. But according to Imad Badi, a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council, there are many complications, including “the precarity of the transition in Libya and its crowded geopolitical theatre, with many other players; the continued interventionism of other states, such as Russia and the UAE; and the divergences over political Islam, which are likely to come to a head” in the run-up to Libya's elections.

Opposition media platforms

Both Turkey and Egypt have been meticulous to avoid a direct confrontation in Libya since the start of the crisis. But negotiations could not have moved forward without a clear understanding of the centrality of Libya for Egypt. Turkish officials have indicated that Ankara can be flexible, remaining in Libya while respecting Egypt’s security concerns.

Another key issue for Cairo is the presence of the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood in Istanbul, a favoured destination for the opposition group after the 2013 coup against the country’s first democratically elected government, led by President Mohamed Morsi. The coup and its fallout cost hundreds of lives and was followed by an unprecedented purge of tens of thousands of critics.

Many of those who fled settled in Istanbul, which became a nexus for opposition figures across the region in the wake of the Arab Spring. Arab opposition figures and intellectuals have enjoyed relatively greater freedom in terms of media and self-expression in Istanbul, growing ever-more critical of their own governments.

As opposition media platforms have thrived in this environment, they have become a key target for the Egyptian government. Reliable sources confirmed to me that Egyptian officials asked for the total closure of these media outlets, but Turkish officials stopped short of that, instead asking them to “tone down” their criticism.

The Egyptian demands were eventually leaked to the media, causing tremendous frustration in Ankara. Since then, both parties have treaded carefully to avoid the collapse of talks, which are clearly vulnerable to external disruptions.

Serious regional threats

Both countries had compelling reasons not to leave the table, with serious regional threats dictating new foreign policy orientations and revived alliances. Both Ankara and Cairo have legitimate concerns over Joe Biden’s presidency, as the US administration has already proved to be antagonistic towards each to a certain extent.

Turkey’s attempts towards rapprochement with former regional allies to reduce its own isolation, and Egypt’s gradual divergence in Libya from the UAE, Saudi Arabia and Russia, are among the key factors driving momentum for a reconciliation. Cairo’s realisation of the limits of counting on a single political or military group in Libya to bring stability to the country has also laid the groundwork for negotiations with Turkey and re-engagement with the Tripoli-based government.

While initial talks in Cairo did not yield any breakthroughs, the discussions were “frank and in-depth”, according to a joint statement, which noted that the two sides would now evaluate the outcome and decide on next steps. A higher-level meeting between the two countries’ foreign ministers, Mevlut Cavusoglu and Sameh Shoukry, is expected to follow.

A comprehensive agreement on bilateral relations and regional issues is unlikely within days or weeks, but an upgrade in diplomatic relations is not beyond the realm of possibility.

If the two states ultimately cut a deal, it would have major ramifications, from appeasement in the Eastern Mediterranean to a bolstered trade agreement. Equally important is for the two states to synchronise cooperation in Libya as it transitions towards political and security stability.

For Ankara, another ambition is also emerging: launching a similar reconciliation process to repair frayed ties with Saudi Arabia and the UAE.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].