Israel's war on Gaza: Was Hamas really operating out of the Al-Jalaa building?

When Israeli F-16s flattened the 11-storey Al-Jalaa building in Gaza City, the Israeli army said the high-rise was targeted because it contained Hamas intelligence assets.

It’s a claim that was repeated by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu the following day on CBS's Face the Nation, without further detail.

Soon after, US Secretary of State Antony Blinken said he had not seen any Israeli evidence of Hamas operating in the building. Two days later, Blinken said the US had received further information, but declined to discuss it.

Those housed inside the building, meanwhile, have denied the claims. Gary Pruitt, president and CEO of the Associated Press, which has had a bureau there for 15 years, says the company “had no sense Hamas was there”. AP chief Sally Buzbee has called for an independent investigation, while Reporters Without Borders has called on the International Criminal Court to investigate.

But will there be a definitive answer - or consequences?

Israel’s bombing of the Al-Jalaa building garnered headlines because of the international media outlets that were located in the building (the facility was also used by by Middle East Eye).

That attention, however, has reportedly led some high-ranking Israeli officials to believe the attack was a mistake - not because it was potentially illegal, but because it has turned international opinion against Israel.

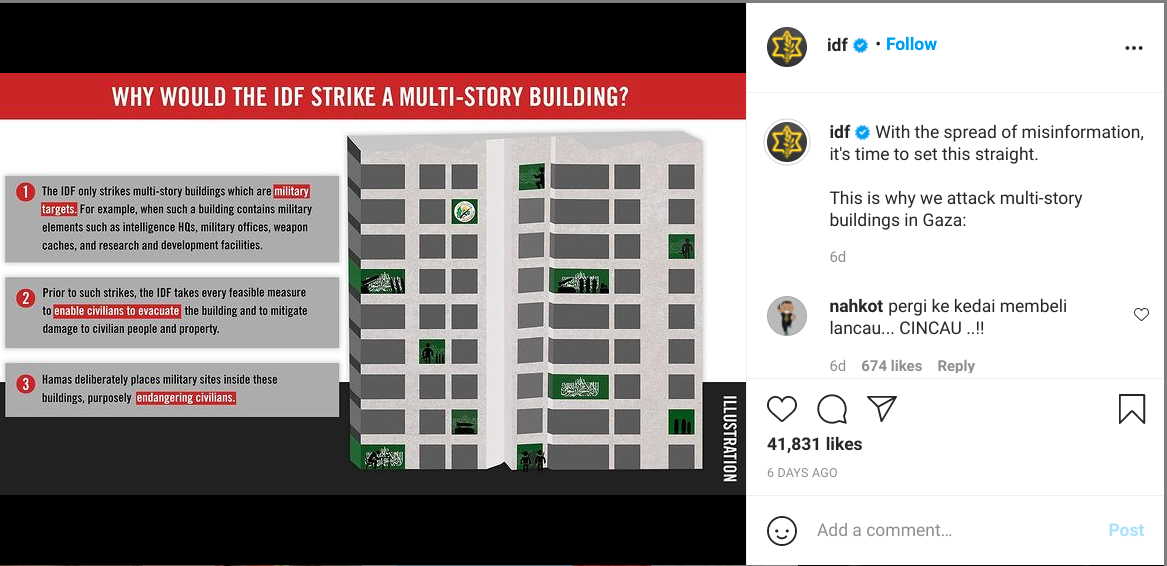

But the attack on Al-Jalaa was not out of the ordinary. The Israeli army regularly justifies attacks on residential buildings, schools, hospitals and other civilian buildings by saying that Hamas or other Palestinian armed groups are operating out of them, claims that receive little scrutiny from the mainstream media or Israel's allies.

MEE spoke to three human rights experts on six key points to find out what these claims mean, whether anyone is actively investigating them - and what happens when evidence suggests they aren’t true.

1. Who checks whether Israel’s claims are true?

There is no single independent entity responsible for investigating Israel’s justifications for bombing civilian targets in Gaza.

That said, individual claims have been investigated by NGOs and by international committees organised by the UN during previous attacks on Palestinian territories.

One example is the Gaza Platform, a digital mapping tool from Amnesty International and Forensic Architecture: it was launched after Israel’s 2014 offensive, known as "Operation Protective Edge", which tracked and analysed Israel attacks using photos, videos, eyewitness accounts and satellite imagery.

But these types of investigations aren’t automatic and don’t happen for the majority of attacks. They are also often conducted without cooperation from Israel, which also actively blocks international investigations into Gaza, so their scope is limited.

“They won’t even let UN investigators in,” says Sarah Leah Whitson, executive director of the Washington, DC-based Democracy for the Arab World Now (DAWN).

She says that 10 years ago, Human Rights Watch, where she was Middle East and North Africa director until recently, sent teams of investigators to Gaza “to expose their lies bit by bit, one by one. Now that’s too difficult. They don’t let them in”.

The Israeli military does carry out its own internal investigations. But Yael Stein, research director at B’Tselem, a human rights group in Jerusalem, cautions "that’s inside the army, so they never have to show anything".

2. If the claims are true, are attacks on civilian targets legal?

The question of what is legal under international law is much more complicated than whether or not these claims alone are true.

The Geneva Conventions were created after World War Two to protect non-combatants during conflict. Specific to our question are articles 48 through 52 in the first Geneva Protocol which states must follow, whether or not they signed up for them. There are two key points to examine.

First, the articles examine exactly what is being targeted. To be legal, the object of an attack must be a military target and meet two criteria: the intended target must give the military forces which control it a clear advantage and the destruction of that target should give the attacking side a military advantage

That means, says Stein, that bombing a house in Gaza City because members of Hamas met, or even lived, there would not be legal.

“Demolishing a house where a phone meeting - or a meeting even with people - it’s not infrastructure,” she says. “It’s not part of the security apparatus of the military. Destroying it won’t give any military advantage to Israel because they can have the meeting in other places.”

What if, for example, Hamas hid 100 rockets in the basement of the same building in Gaza City. Stein says that this would make the building a legitimate military target.

But then there is the issue of proportionality to consider - and this is where the second key point raised in the articles comes in.

“You have on the one side the civilian loss that is anticipated by the bombing," Stein says, "and, on the other hand, you have the military advantage that you anticipate from the bombing.

'Israel did Cast Lead. Israel did Protective Edge. Israel is doing it now'

- Yael Stein, B’Tselem

“If you anticipate that the military advantage is higher than the civilian loss you anticipate, then it would be a proportionate bombing.”

Such legal definitions are subject to interpretation. Stein says that she, of course, would have a different take on the situation from a military officer. But even in this grey area, Israel has, in her opinion, regularly overstepped the bounds of reasonable legal interpretation.

“Israel did Cast Lead. Israel did Protective Edge. Israel is doing it now,” she says, in reference to Israel's previous attacks on Gaza in 2008-2009 and 2014 respectively.

“They bombed against every rule of international law," she says, "against every instinct of morality, they just bombed and killed unproportionally all those civilians with no legal justification, with no proof and they get away with that again and again.”

3. Was bringing down the Al-Jalaa building illegal?

Experts say more details are needed about what was actually targeted in the building by the Israeli military forces to make their judgement call. But many believe, on the evidence they have, that the bombing was illegal.

Saleh Hijazi, deputy regional director for Amnesty International’s Middle East and North Africa office, points to reports, in Hebrew media, that Israel told Washington that a Hamas military intelligence unit was inside the building, scrambling Israeli military signals at sea and providing information to help Hamas make attacks.

But Hijazi says that even if the reports are true, it still leaves the question of proportionality.

"Israel does have the ability to carry out what they call surgical strikes and they’ve demonstrated that over and over in the past, and including in this military operation," he said.

“Was it proportionate to take down the whole building? It’s really hard to imagine that that was a proportionate attack and disproportionate attacks are war crimes,” he says.

With the end of the latest assault, Netanyahu declared in a speech on Friday: "We regret every loss of life, but I can tell you categorically, there is no army in the world that acts in a more moral fashion than the army of Israel."

Morality aside, Stein says that to her mind the attack on Al-Jalaa was illegal. There would have to have been immovable military infrastructure - like a military base on one of the floors - to justify such an attack. In any case, the attack would not have been proportional, she says.

Demographics could also feed into the debate. Gaza is one of the most densely populated places in the world, with just under 5,500 people per square kilometre.

One could argue, Stein says, that given over-crowding, any bombing from the air will, by definition, be disproportionate, unjustified - and therefore illegal.

“Israel keeps saying that international law is not applicable to the ‘war against terror’. But this is of course nonsense. The civilians are there. We can’t just make them disappear.”

4. If these aren’t military targets, why hit them?

One justification that Israeli officials have given for the destruction of civilian infrastructure in Gaza is that it will change the political dynamics in the Palestinian territory to Israel’s eventual advantage.

But that’s also not a legal justification to bomb, says Stein.

‘This is one of the things they say in public relations: ‘We are demolishing all of those very tall houses with seven- or nine-storey buildings in Gaza and then the people in Gaza are taking it hard and therefore they will push the Hamas government to stop bombing Israel.' That is not military advantage.”

Hijazi says that the real reason targets like high-rises are picked is very similar to the siege of Gaza, which began in 2007: collective punishment.

“Israel wants to inflict pain. They still think that this is good logic to follow. The more we inflict pain on the people of Gaza, the more they will turn on Hamas,” Hijazi says.

“This is, of course, totally illegal. You do not push civilians in order to force the government to change the policy.”

5. Are Hamas and other armed groups breaking the law?

It is beyond question that Hamas and other armed Palestinian groups are breaking international law when they fire rockets indiscriminately into Israel.

Stein says: “Of course, what Hamas is doing is a war crime and, of course, it’s illegal." However, she says, the number of civilians killed and injured by these rockets in Israel is so much lower during operations against Gaza that comparison between the two is unhelpful.

"This is illegal and this is illegal," she said of comparing attacks on civilian targets by both sides. "So what? I think Israel is the one who has much more power, its actions are much more affecting life and property. You can’t really compare."

Additionally, Stein says, just because Hamas or other armed groups break international law, that doesn’t justify Israel’s war crimes.

“The line of Israel is that: ‘Well, Hamas is throwing rockets. We told them not to do that. We told them to evacuate their houses’,” she says.

“This actually means: ‘They are doing it, we told them to stop, they refused, so we can do whatever we want’.

“This argument is so wrong from the legal point, the moral point. Israel cannot do whatever it wants in reaction to the illegal things that Hamas is doing.”

6. If Israel broke international law, what next?

There are three main options of legal recourse for international investigators and states, namely universal jurisdiction, the International Criminal Court or the UN Security Council. Each have their limitations.

Courts in countries that have universal jurisdiction laws may prosecute individuals for crimes against humanity even if the crimes happened in another country or were committed by leaders of another state. However, in recent years, many states have limited the use of universal jurisdiction, including the UK, which ammended its laws in 2011 to protect Israelis.

The ICC has global jurisdiction to investigate and try those responsible for the world's worst crimes when states are “unable or unwilling” to do so themselves. The court announced in March that it had opened an investigation into possible crimes committed by both Israelis and Palestinians in the West Bank, Gaza and East Jerusalem since 13 June 2014. Israel has said it will not cooperate with the investigation. The latest attack on Gaza may very well become part of that investigation, but the entire process is expected to take years to complete.

The UN Security Council has the authority to say that what Israel is doing is illegal through issuing resolutions or even applying sanctions. However, the US regularly vetoes these types of resolutions. In 2016, for example, the US was the only UN Security Council member to veto Resolution 2334, which said that Israel’s settlement activity violated international law and called on Israel to stop.

Experts point out that these processes are only as strong as the political will of states and governments to carry them out. And at this moment, the will-power of the most powerful countries, namely the US, is in question.

“We live in a world where the international court doesn’t have international troops to send in and has to rely on member states to enforce its warrants and uphold its decisions, so the international community is very weak,” says Whitson.

“China does whatever it wants and nothing stops it. Syria does whatever it wants and nothing stops it. The difference with Israel is it’s the US that’s the one that’s not stopping it. China doesn’t claim to be the human rights leader of the world and neither does Syria. The US does and that's the incongruity."

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].