Lebanon: How Beirut's bookshops kept love of literature alive during war, boom and bust

The Ras Beirut Bookshop was a beacon of intellectual life and diversity of thought in Beirut for the past half century, until a 13-story glossy, beige-coloured stone high-rise knocked it down in 2008.

“Maybe we were lucky it happened like this because the economic situation for bookstores and publishing houses today is at rock bottom,” Fadia Jeha, the former owner of the bookstore, told Middle East Eye. Jeha was forced to close down her shop after the building’s owner changed and a court case concluded that all prior tenants had to be vacated.

On Bliss Street, four buildings down from the new high-rise, lies an abandoned establishment with blue graffiti on its wooden-boarded windows. It reads: "Eat the rich." The sentence refers to a general sentiment of anger against the ruling class whom Lebanese blame for endemic corruption, economic mismanagement, and criminal negligence that resulted in the August 2020 port blast.

In the past year and a half, the local currency has lost 85 percent of its value and consumer goods prices have soared. With hundreds of businesses permanently shutting down since the October 2019 mass anti-establishment protest movement, bookstores have also taken a colossal hit in revenue.

Today, Lebanese bookshop owners are forced to use creative means to stay afloat and survive the crisis.

Ras Beirut’s literary past

Before the founding of the American University in Beirut (AUB) in 1866, known then as the Syrian Protestant College, the Ras Beirut neighbourhood was a semi-rural area hosting livestock and farmers, as shown by photographs taken by AUB professor Franklin Moore between 1892 and 1902.

An influx of students and teachers from the villages and mountains of Lebanon arrived in tandem with the university’s construction, inspired by the goal of learning and teaching. The growth of Ras Beirut reflected the institutional invasion of the desolate farming terrain.

Bliss Street, in the Hamra district of Lebanon’s capital where the university still stands today, became a home for the newly settled. Businesses were built shortly thereafter to provide basic necessities: food, drink, lodging and school supplies.

In 1949, Antoine Karam, a professor of Arabic literature at the university, opened the Ras Beirut Bookshop. Four years later, it was bought by Shafik Jeha, a teacher and educational pioneer who launched the county’s first civics education programme and co-authored the state’s high school history book.

Beirut’s Hamra neighbourhood has often been romanticised as the one of the most arresting and cosmopolitan urban centres in the Arab world during the 1950s-60s, and perhaps for good reason. As noted in Robyn Creswell’s City of Beginnings, “Hamra was a contact zone for artists and militants from the far left to the far right, nationalists and internationalists, experimentalists and traditionalists. In this highly politicized boheme, journals of ideas flourished and each coterie had its own cafe.”

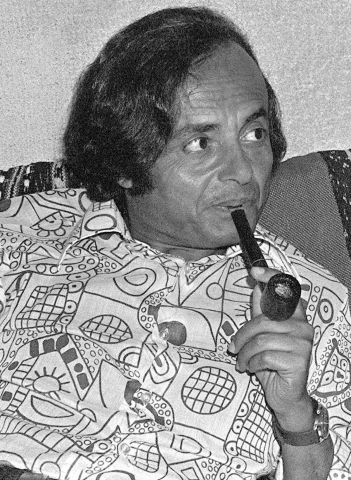

During those years the store was maintained by Abd al-Ahad Barakat - or “Amo Abdo'' as he was known amongst the bookstores’ clients. Adonis, the avant-garde Syrian poet (Edward Said described Adonis as the first international Arab poet) had been coming to Beirut and frequently visited, alongside other pioneers of the revolutionary free-verse literary Shi’r [Poetry] magazine, including its founder, Yusuf al-Khal, as well as Muhammad Dakroub, the Marxist critic and editor of Al-Tariq cultural journal and countless other important writers.

In 1969, the Marxist philosopher Sadiq Jalal al-Azm was infamously expelled from AUB for publishing his book Naqd al-Fikr al-Dini (Criticism of Religious Thought, published by Dar al-Taliah, Beirut), which was virtually removed from all local bookshops. Yet Amo Abdo kept it on the shelf - maintaining the bookstore's ethos of intellectual freedom - where it stayed despite this intellectual battle fought across the cultural scene.

The cultural fermentation continued for 20 years, and it seemed that the old, famous saying: “Cairo writes, Beirut prints, Baghdad reads” was truer then than ever before - until 1975 when the civil war erupted. At that point, Shafik’s daughter Fadia Jeha filled the vacuum, happily greeting visitors and advising them on new books. Often times "big literary names" kept appearing.

“I remember when I started working that Hisham Sharabi’s first stop, upon landing in Beirut, would be our bookshop, to see who he knew in the city,” she says. “Another time, when a German (Hartmut Fähndrich) translated Emily Nasrallah’s work, he wrote the initial proposal and left it in our bookshop for her to see.”

Despite the chaos of the country during the war, she developed the store with unmitigated care and devotion, earning the title of Beirut’s most renowned maktabajia (or librarian), according to the Lebanese newspaper Al Akhbar. During the most intense battles, she would open its shutters in the morning and leave quickly thereafter. But the publishing and gathering continued.

'Al Khayat is now a bank. Ras Beirut Bookshop is now a high rise'

- Rima Rantisi, lecturer at the AUB

“We were in this unparalleled, unique, small geographical location where people did not try to put each other into boxes or interrogate others’ identity.”

Before, during and after the 15-year war, Ras Beirut Bookshop played far more than just the role of a bookstore; it was an intimate refuge and a second home to many.

“I was born and raised in Ras Beirut, and this particular bookstore was part of the itinerary of my positional relations since I was a kid; we used to go with my parents to buy the stationery and our school books,” says Maher Jarrar, AUB professor in the Department of Arabic & Near Eastern Languages.

“During my years at AUB as a student it became kind of a habit to drop by on a quasi-daily basis and lose myself for a long while among the shelves.”

To mark the 50th anniversary of Ras Beirut Bookshop’s opening, in 2004, the store published a book collecting testimonials from customers over the years, memorably recreating the atmosphere of the bookstore.

Saree Makdisi, professor of English and Comparative Literature at UCLA, wrote: “For those of us who come to Beirut from America, the experience at Fadia Jeha’s bookstore is a welcome reminder of the way things used to be, and the way things ought to be.”

Later, with the rise of the internet, Jeha would send a list of the newly released books each month to different customers and universities, from Japan to the United States.

Nostalgia for Beirut in the 1950s and 60s is common these days in the increasingly gloomy present, especially amongst the younger generation. Yet the notion of a rosy, pre-civil war past ignores 50 years of history. In this light, yearning for former spaces such as the Ras Beirut Bookstore is more than just a sentimental desire.

“Closing down this ‘symbolic’ gathering space made of books, shelves, and people to which I was mentally, socially, and physically entwined gave a signal that bits of my ‘mental geography’ are sliding away," Jarrar says.

"But this was the reality of the drastic changes forced on the urban spaces of Beirut which were caused by the aggressive ‘war machine’ that ruined the familiar intersections of dwellings and eviscerated the neighbourhoods of their spirit.”

Preserving memories

In the spring of 2008, coinciding with the closure of the Ras Beirut Bookshop, the neighbourhood sat on the cusp of another construction boom, followed by major spikes in rents as more and more investors turned their eyes and wallets to the city.

At the same time, Rima Rantisi, a lecturer at the AUB and editor of the literary magazine Rusted Radishes, moved to the neighbourhood.

“Of the biggest casualties were the bookshops that had to close, particularly Ras Beirut Bookshop and Al Khayat, both on Bliss Street,” she recalls

“Al Khayat is now a bank. Ras Beirut Bookshop is now a high rise.” Four Steps Down bookstore was also shut down and replaced by a boutique Dubai Market shop.

Trying to preserve these precious memories, Rusted Radishes began a tour of the neighbourhood bookstores in 2019, during the early days of the revolution, and most recently held another tour on 24 April, where they visited a few of the over 15 bookstores in the district, including Al Furat, Bissan, Diabco, Way In and Barzakh.

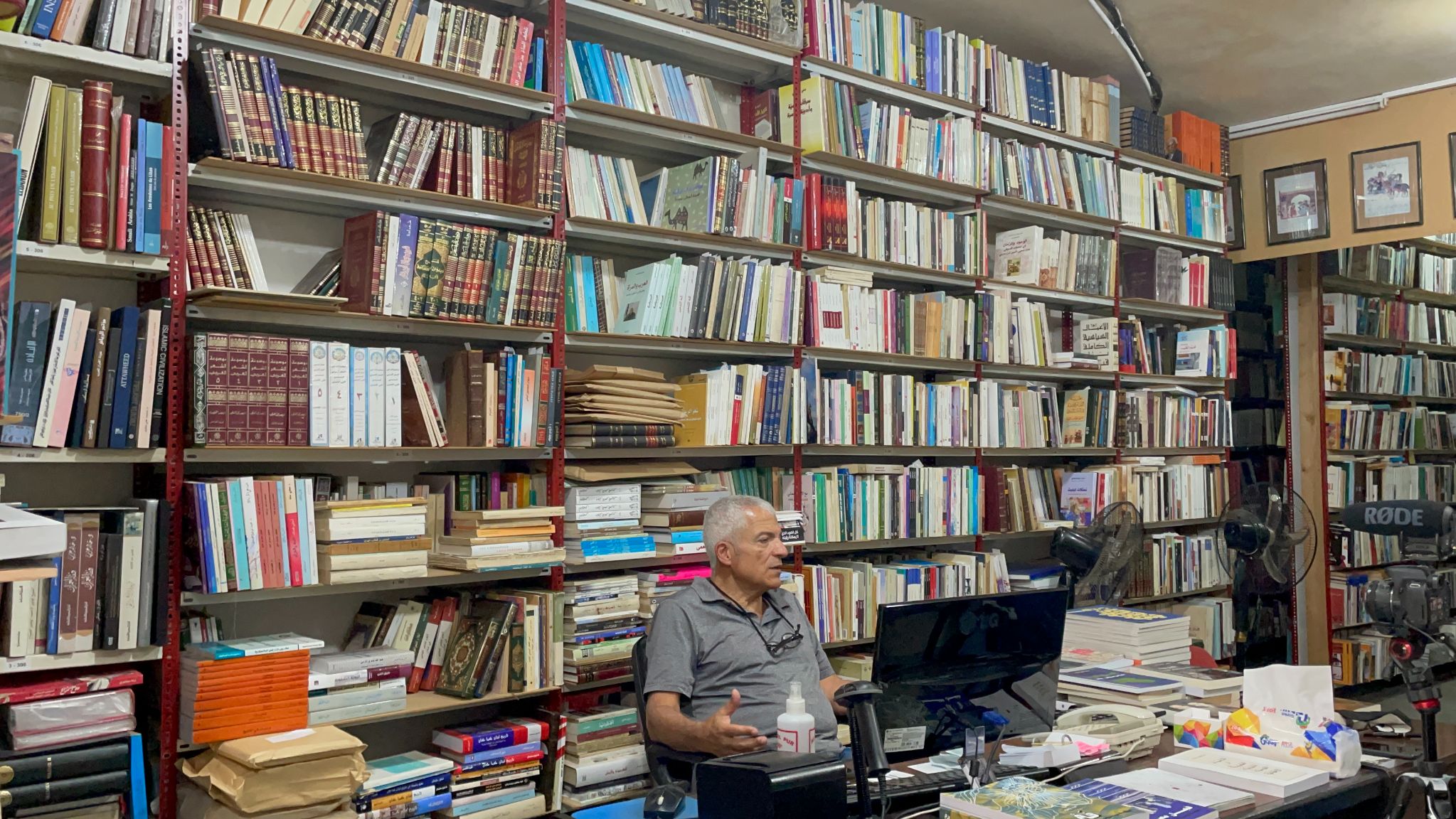

The tour’s first stop was Al-Furat bookstore - which focuses on Arabic books, magazines, manuscripts and posters and whose name eponymously translates to the Euphrates river.

Abboudi Abou Jaoude, the store’s owner, told MEE that sales have diminished in the past year, between 90 to 95 percent. “This is natural considering the collapse,” he explains in front of a group of mainly university students who huddle around his desk, with stacks of books surrounding them.

“The last thing a normal person thinks about, unfortunately, is buying a book, because his priorities are different. He needs to eat, raise his family, and to send his kids to school.”

Atop of the economic crisis, the coronavirus mercilessly spread across the country, overwhelming the healthcare sector. In the past year, the government has imposed several lockdowns, enforcing an odd-and-even license plate rule for alternating days and closing most businesses - including bookshops, which suffered plummeting sales.

'The last thing a normal person thinks about, unfortunately, is buying a book... He needs to eat, raise his family, and to send his kids to school'

- Abboudi Abou Jaoude, Al-Furat book shop

“If our market was not based on a personal website and an online exchange, we would not have sold books in these conditions,” said Abou Jaoude, joking that his bookstore’s name should change to the Amazon River, instead of Euphrates.

Yet even with international sales, the revenues are relatively meagre, “since not many people abroad trust Lebanon’s market and are afraid to buy from here”.

The Way In Bookstore was known for handwritten tags detailing the price and how much it had in stock. Yet today, with the prices changing so much, the staff frequently have to scribble in with pencil a new price.

A House of Many Mansions: The History of Lebanon Reconsidered by Kamal Salibi costs 371,000 lira, the equivalent of what used to be $247 dollars at the old exchange rate, supposedly pegged at 1,500 lira per dollar.

The bookshop has a unique collection of European and American newspapers, French magazines and scholarly journals including the Journal of Palestine Studies and Jerusalem Quarterly.

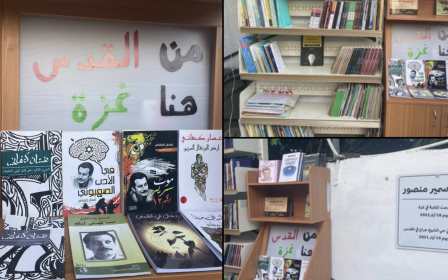

By far the most apparently disorganised bookstore is Bissan, which prides itself on its “secular” spin and has a clear ideological commitment to a Greater Syria before the imperialist cartography of the Sykes-Picot Agreement divided the Middle East.

Yet the store’s employees point customers to books within a minute and are able to get their hands on almost every Arabic book.

The bookstore sells massive poetry collections that include the complete works of Mahmoud Darwish, Adonis, Kahlil Gibran, in addition to works of Michel Foucault and Malcolm X translated into Arabic.

On the day of the literary magazine’s bookstore tour, the third since 2019, the sky was clear and the sun shone brightly on the group of bibliophiles, many of whom were emerging from their homes for the first time since Covid confinement. As the group of 30 or so youths formed long lines crossing the streets of Beirut’s central commercial district, cars waited and drivers smiled behind the glass.

“Beirut had been so dark, but that day I was like: damn, I'm so happy that people are still here and that they love books so much,” Rantisi recalls.

Reading culture

According to Index Mundi, Lebanon’s literacy rate was at 95 percent in 2018, ranking amongst the highest in the Middle East, just behind Palestine, which has one of the highest literacy rates in the world.

Yet Abou Jaoude does not believe that many students are reading books these days - or are in tune with Arabic literature being produced from the region, or in Lebanon. “Everyone just wants to leave the country,” he says. “So students are not focused on reading novels but on practical skills to apply elsewhere.”

For former bookstore owner Fadia Jeha, however, “it's not that people are not reading. It is that they want to eat first of all.” Books, everyone can agree, have become a luxury.

“The bookstore situation in Beirut is as bad now as it could possibly be. A book that costs $4, which used to be 7 liras, now costs at least 60 liras,” Jeha said.

Rantisi laments the fact that she has not bought a book in a long time. Teachers and professors are acutely aware of the high costs and many have moved instead to free online editions, PDFs, or photocopying short pieces. Students as well have been severely affected.

Sarah Tello, 18, an incoming sophomore at AUB majoring in Arabic literature and language, says that when she was locked up because of Covid, her immediate thought was to read more. “But then the immediate thought after that was, what about the price of books? The economic situation doesn’t help at all and so I have been purchasing books less and less.”

Tucked in the same building as Beirut’s Presbyterian church lies the neighbourhood's only library. The initiative was founded in 2019 by Nicolette Hutcherson, a social worker who moved to Lebanon with her family in 2008 to run an NGO that takes care of at-risk children.

After years of receiving book donations at the NGO's foster home, she decided to start a small non-profit library in 2019, at the same time the lira plunged. Now, with over 100 books in and out of circulation per week, she notices that her library has filled an essential community need.

“I run a classified page on Facebook for mums and notice that a lot of people ask about where they can find books at the old price,” she says. “So I jump in and say ‘If you want to borrow, we have this library.'"

'Lebanese kids are not going to school in their mother language, so they are not learning to love to read in their own language: they are reading English or French, which for most kids is a second language'

- Nicolette Hutcherson

Lebanon’s educational system has long neglected the language arts and focuses more heavily on the science and technology fields. But Hutcherson believes that the problem is bigger than this.

“Lebanese kids are not going to school in their mother language, so they are not learning to love to read in their own language: they are reading English or French, which for most kids is a second language.”

For Tello, the culture of reading growing up was almost non-existent. “Reading in Lebanon, but also outside of Lebanon, is generally discouraged by society, and it was in my experience,” she says. In school, during breaks, she would pick up a book and start reading only to be “met by extremely peculiar looks”.

Today, she faces a lot of stigma as an Arabic literature student from her family and society. “First I face shock… ‘why would I study something like this,’ then people say that it’s easy and useless. And lastly, that I would have one job, which is teaching, and it is a dead-end job, so I will be stuck here.”

‘It was heaven’

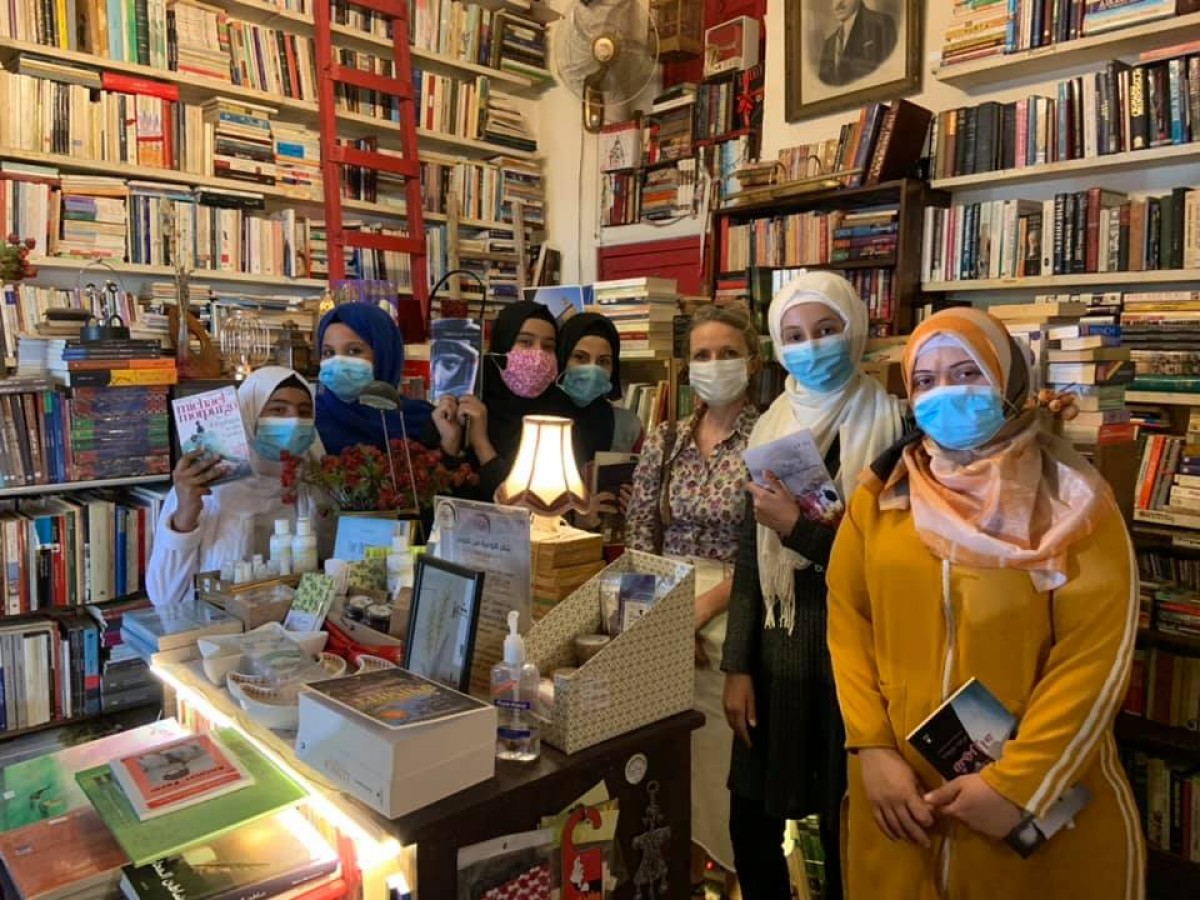

For some, the power of reading is inextricably linked to a brighter future. The Alsama project, a Lebanese organisation that provides education for teenagers living in the country’s refugee camps, recently organised a trip to take refugee girls to a bookshop.

In May, creative writing teacher, publisher and Alsama CEO Meike Ziervogel took six of her “keenest students” from the Shatila camp teenager education institute to visit the nearby Halabi bookshop. For many, it was their first time inside a bookshop.

Maram, 14, a Syrian refugee from Deir Ezzor, bought a book by the celebrated British author Michael Morpurgo with the support of Al Sama. In describing her first time in the bookstore, she says “it felt like it was heaven”.

Wisal, 14, another Syrian refugee who studies at the centre and came to Lebanon in 2017, explains that reading to her is more important than technical skills. “When I read, I learn a new opinion. But on the computer, I cannot feel anything.”

Both girls’ mothers are illiterate, and their fathers can barely read.

Lana Halabi, the owner of the family bookshop that was founded by her grandfather in 1958 as a grocery store that stored magazines, recalls how happy the girls were when they visited.

“They were excited to look through everything and I helped them a lot by proposing books they might like according to their tastes, and a couple of them wanted some English books.”

In the war, the bookshop closed intermittently when fighting engulfed the city, but the store remained open afterwards, collecting so many books that by 2005 no one could step foot inside. It was organised and arranged categorically in 2016 by Halabi.

Her grandfather poses in a framed photo in the back sporting a stern face, a handlebar mustache, and a tarbush, the traditional red-tasselled Ottoman hat worn in the Middle East until the empire disintegrated at the end of the First World War.

She says that in 2016, when she first started attending street markets, they were among the only shops promoting books amidst a mass of retail stores selling businesses clothing, food and accessories.

“When we went, people used to comment ‘seriously are people still reading?’ In 2018-2019, people started knowing who we are as al-Halabi bookstore since they followed us. The fairs and social media have really helped our sales.”

Now Halabi agrees - like every other bookstore owner - that the economic challenge is an enormous burden. Yet she thinks that she has managed to keep sales going because she has kept old books bought at the former rate at roughly the same price as before the crisis.

“However, we are now facing more pressure to increase the prices gradually but not drastically.”

For example, the rates they sell are around 3,000 or 4,000 liras to the dollar – as opposed to the near 13,000 hovering on the black market. “All the supplies, printing supplies and marketing material are on the daily rate, so we are forced to adjust. However, you will notice we are a lot cheaper than other places.”

Although Rantisi continues to feel bad about not buying books since the collapse started, she vows that things will change: “We cannot continue like this. We want to support the local bookshops.”

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].