A prayer for Lydd: Maps and memories that the Nakba could never erase

In the province of Lydd (or Lod), Palestine, my ancestral family lived for generations in the village of Jimzu. It was ethnically cleansed by Israeli forces in 1948, in a military offensive called Operation Danny.

Army commander Moshe Dayan, who later became Israel’s defence minister, gave the orders to conquer Lydd, Ramle and all other villages in the region. The goal was to ethnically cleanse and depopulate Jimzu and the surrounding villages, “torching everything that can be burned”.

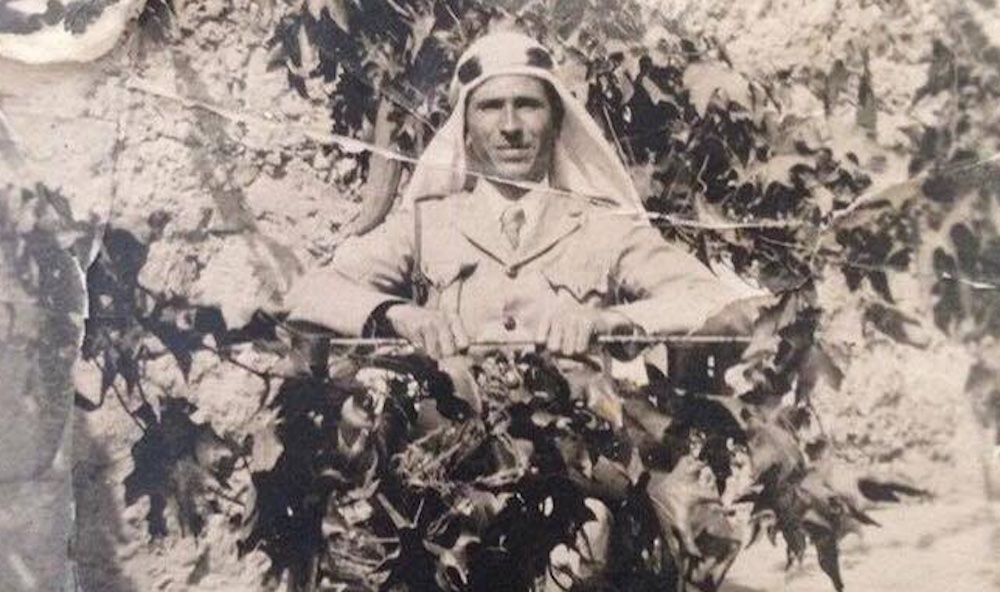

My great-grandfather, Issa al-Jamal, snuck back into his village after the military operation was over. He recalled seeing the remains of dead people scattered all around the village, unburied: “It’s as if their bodies were dismembered by wild dogs.”

My uncle's map is a damning reminder that Israel is an occupying power that could only exist by forcing generations of Palestinian families from their homes

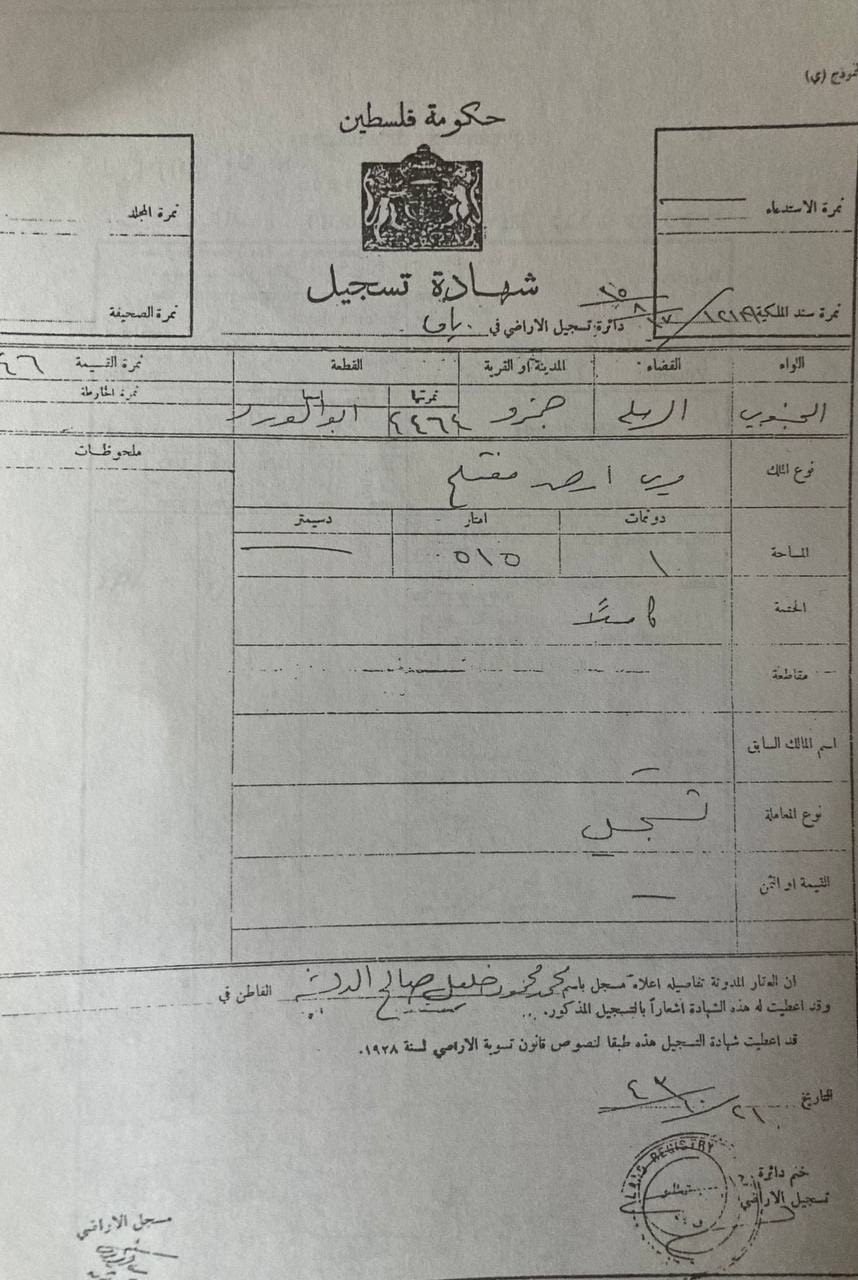

Most Palestinians from Lydd could not salvage any personal belongings. Our homes were destroyed, along with almost all physical proof of our existence in Jimzu for centuries. Israel’s ethnic cleansing, however, did not stop our oral histories from becoming the focal point of our identity. Our stories kept our history in Lydd alive.

My great-grandmother, Maryam Naseef, ran the village’s bee colony, making gallons of honey every year to support her family. Yesterday, I sat around the dinner table with her grandchildren here in New York, as they recalled that Umm Hussein (the mother of Hussein) was the toughest Palestinian woman our family knew.

She used to say that even when she was underground, she would still be “the woman of the household, the woman who was in charge”. Her papers issued in Jericho after the Naksa showed she was born in Lydd in 1912.

My grandfather, Mohammed Issa al-Jamal, learned in the schools of Jerusalem. He was one of the first village educators, and he taught in Ramle. He also started a chapter of the Boy Scouts that he called al-Najjada, which aimed to unite the youth and to strengthen their Palestinian consciousness. Inspired by the Palestinian paramilitary scout movement, al-Najjada was founded in Jaffa around 1945. The Jimzu branch was, according to my family notes, more of a peaceful resistance movement and did not engage in any military activity.

My grandfather, one of the very first activists in my family, understood the dangers of the Zionist settler-colonial project, and he made sure to educate his village to keep our existence alive. In many ways, al-Najjada became an organisation of resistance against Zionist settler-colonialism. Palestinian professor Reja-e Busailah has written that from a certain point on, “the people of Lydd outwardly adopted, invariably, an attitude and strategy of defence”.

My grandfather brought the idea of al-Najjada to the village, along with annual festivals, to which surrounding towns were invited, to drum up support for resistance. On one occasion, the festival was interrupted by a British army raid targeting Jimzu. They wanted to squash any support for resistance - especially armed resistance. My great-uncle, Ahmed Issa Ibrahim al-Jamal, recalled in his memoirs that there were about 14 rifles among the townsfolk.

The rifles were collected hastily, and my great-uncle quickly hid them in the fields behind the house. The British army drove into town, stopped everyone, and searched those who were present for arms. Of course, they did not find any, and they eventually left.

My great-uncle recalled that the festival resumed, food came out, speeches were made, and recruits and contributions were collected - despite the seething anger of the townspeople at the person who had informed the British of the event (who my great-uncle says did not like my grandfather).

'She could only cry'

My great-uncle was the town leader of Jimzu. He accompanied his father (my great-grandfather) to carry out a census of the population of Jimzu. He knew every resident and every family.

But on 9 July 1948, my great-uncle and the rest of the family were forced to leave, as the Zionist Yiftach Brigade advanced and occupied Jimzu. As my family and the remainder of the village residents were expelled, Zionist militias shot at them while they fled. Ten were killed.

'You prevented a small child from experiencing the love of a mother before the sun set'

My great-uncle recalled in his memoirs that he witnessed a mother, Nazeera, breastfeeding her baby, Mali, as they were forced to leave their lives behind. A Zionist soldier shot the mother; the baby continued feeding on her lifeless body.

My great-uncle wrote a small poem on her behalf: “You [former Israeli leader Ariel Sharon and Dayan] attacked Jimzu with a massive army. One day, however, you will lose. You kicked the residents out of our village, and their families. You followed them with machine guns and tanks. You killed the old - and their children. You killed them without reason. You killed an old man - a leader - a man who was too old to run or hide. It then wasn’t enough what you did - you had to kill Nazeera while her baby was breastfeeding on her bosom.

“You made death everywhere and became an expert in killing us. The innocent child - what did she do to deserve no father? No mother? You prevented a small child from experiencing the love of a mother before the sun set. The small child tugged on the breast of Nazeera. She could only cry.”

From there, my great-uncle had to find a new home. In October 1956, many members of my family became refugees and settled in Jordan. Some had to move to the United States. Others had to find refuge in any country that would take them, such as Brazil.

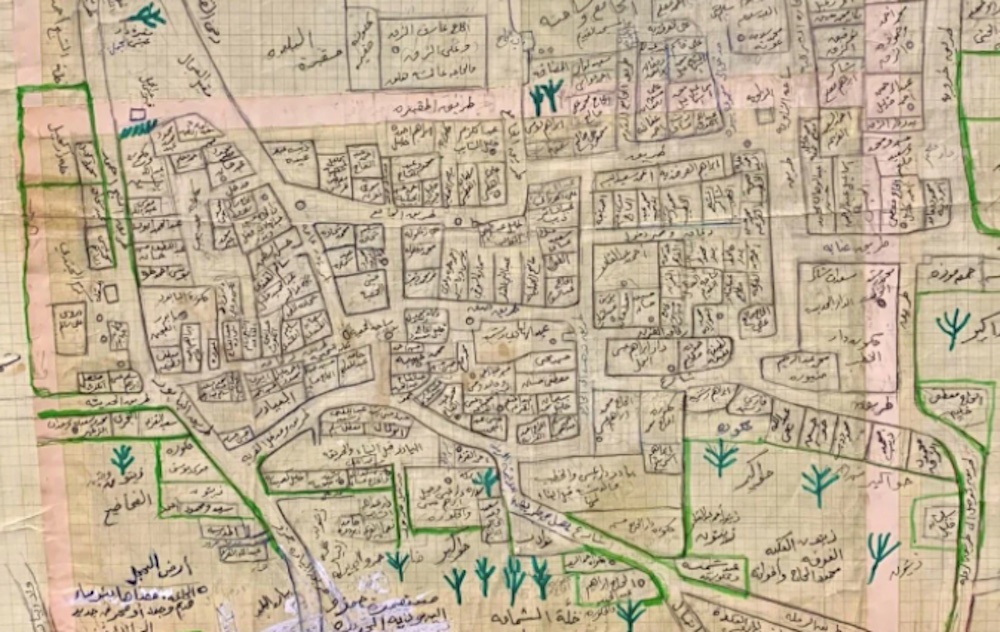

For my family, remembering the remains of our home was everything. My great-uncle drew the most detailed map of Jimzu that currently exists. No family home, well, field, mosque, or street was forgotten. He kept the people of Jimzu and their stories alive by virtue of his memory.

The map my great-uncle drew was displayed at the Spertus Institute for Jewish Learning in Chicago as part of the “Imaginary Coordinates” exhibition - albeit not for very long. Under intense pressure from angry Zionist patrons, Spertus closed the exhibition. The pretext put forward by critics was that it “was clearly anti-Israel” and that it tarnished Israel’s reputation. They were “saddened” by my uncle’s map.

Clearly, any reminder that Palestinians used to live on their land angers Israel’s supporters. It is a reminder that their state was built by ethnically cleansing and destroying Palestinian villages, such as my ancestral home of Jimzu. My uncle’s map is a damning reminder that Israel is an occupying power that could only exist by forcing generations of Palestinian families from their homes.

Palestinians have returned to Lydd and Jimzu since their forced exile in 1948, but as visitors - and sometimes they can’t even do that.

Freedom denied

I tried to visit Jimzu in 2016. I have seen photos of the ruins of my ancestral land, including the only standing grave of my maternal great-uncle, Jamal Abdellatif Shehadeh, who died in 1946. I wanted to pay my respects in person.

But Israeli settlers did not let me enter my village or see his grave in person. The painful knowledge that Palestinians cannot even pause to remember everything they’ve lost is further cemented by the reality that Israeli settlers are still kicking us out of our homes to this very day.

Although resistance against the occupation in Lydd has been suppressed for decades, we’ve seen an unprecedented wave of protests across Israel in recent days. Palestinians are reasserting their identity by taking to the streets. My home, Lydd, wants the world to know that they will not be called “Arab Israelis”.

The protests showed solidarity with the families of Sheikh Jarrah, Jerusalem as a whole, and Palestinians in Gaza facing brutal Israeli bombardment and a 14-year military siege. Palestinians in Lydd are showing the settler-colonial state that their containment policy will no longer work, as long as apartheid continues.

Memory is a powerful tool of resistance that fuels the liberation movement today. The right of return is the most crucial part of the Palestinian struggle. The story of my family and their life in Jimzu is not unique; Palestinians across the diaspora can recall hearing about the beauty of our villages, and the eagerness in our grandparents’ voices as they pray to come home.

There is no freedom without our right to return, from the river to the sea.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].