Turkey-Egypt rapprochement: Political exiles live in fear amid thawing of relations

When Amr’s mother went to visit his brother in an Egyptian jail, the police guards told her: “Turkey will deport your son very soon, and he will pay the price for his negative coverage of Egypt.”

As a political exile living in Turkey, Amr Hashad was terrified by this threat on his security. He knows very well the inside of Egypt’s prison system, and what authorities do to outspoken opponents of the government.

Arrested in Egypt in 2014, Amr was detained for five years and moved between 11 different prisons, where he was tortured regularly.

Within one month of his release, Amr had escaped to Turkey because it is common knowledge that political prisoners are regularly re-arrested. As a punitive measure, security forces arrested his brother, whose leg has been amputated. He remains in jail to this day.

After his escape, Amr became one of roughly 33,000 Egyptians living in exile in Turkey, once seen as a safe place away from Egypt, where the current administration has rolled out an unrelenting crackdown on dissidents who have been forcibly disappeared, systematically tortured, and given lengthy prison sentences following mass trials.

But fear is growing that this situation is about to change, following the developing rapprochement between Cairo and Ankara after nearly a decade of hostility.

The thawing of relations was clear in April this year when the foreign ministers of the two countries exchanged good will wishes ahead of the holy month of Ramadan. From here, rhetoric between officials took a notably warmer turn.

Mutual maritime interests

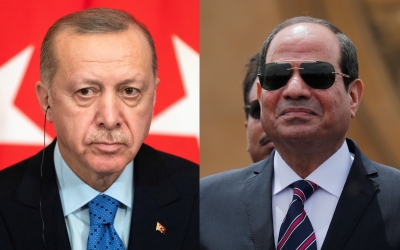

Most analysts pinpoint Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi’s rise to power eight years ago as the moment Turkey and Egypt became foes. Then Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan, an ally of the late Mohamed Morsi, the president Sisi overthrew, fiercely condemned the military takeover, accusing Egypt of carrying out state terrorism.

The coup was a blow for Turkey. Following the 2011 Arab Spring, Ankara had hoped it could forge closer ties with Arab countries, including Egypt, Khairy Omar, an assistant professor at Turkey’s Sakarya University, told Middle East Eye.

Morsi's overthrow was a major source of tension, and the ambassadors of their respective countries were sent home. At international conferences, Egyptian and Turkish officials refused to speak to each other. Ankara and Cairo took opposing positions on regional conflicts, including the blockade on Qatar.

Egypt signed an agreement on maritime delineation with Greece last year, which Turkey then described as “null and void.”

Now, though, their geo-strategic interests appear to be aligning, and the two countries have found common ground, particularly over Libya and maritime borders in the gas-rich eastern Mediterranean.

“In Libya, Egypt’s decision was not to enter a clash with Turkey, and also in the Mediterranean,” said Omar. “Egypt wanted to preserve its water borders and considered that its problem was not with Turkey.

"The decision to demarcate the water borders according to the Greek plans would have deducted about 40,000 square kms from Egypt's rights in the Mediterranean, and there were groups in the Egyptian Ministry of Foreign Affairs who saw that sharing dialogue with both Turkey and Greece would be better.”

It is analysis like this that has rattled Egyptian exiles in Turkey. “I believe that the value of the youth isn't as valuable as the economic or strategic benefits Turkey can gain from the reconciliation,” Amr told MEE.

Many share his fears that Egypt will request those living in political exile to be handed back as part of a deal with Turkey. Back home, Egyptian exiles face torture, detention in squalid conditions, and perhaps even the death sentence.

During the eight years of icy relations, Egyptian opposition members fled to Qatar, Sudan and Turkey in their thousands, but made their biggest impact in Istanbul, where they established several high-profile TV channels watched by Egyptians across the world.

These satellite channels provided a platform from which Egypt's opposition could criticise the administration in Cairo and its consistent human rights violations, something that was not possible back in Egypt, where such dissent results in prison time - and worse.

It makes sense, then, that the first piece of news that brought home the rapprochement and its potential consequences came in March and spread quickly across social media platforms: Turkey had told the three main Istanbul-based opposition media channels, Mekamaleen, Al-Sharq and Watan, to tone down their criticism of the Egyptian government.

Moataz Matar’s famous political programme, With Moataz, on Al-Sharq TV, was shut down. Others began to amend their editorial policy. Commentators wondered if this was a harbinger for something far worse.

It was. Last week, Turkey asked top media personalities Mohamed Nasser, Hamza Zawba and Hesham Abdalla to shut down their shows, and for Matar to stop broadcasting from YouTube, where he had transferred his programme.

'We are very concerned'

Others are beginning to wonder if Turkey will start deporting Egyptians at the request of Cairo.

“The short answer is yes, sure, we are very concerned about that,” said Omar, a former Egyptian political prisoner, and now a journalist living in Istanbul.

“But is Turkey going to do that? Some people don't think so, especially with the huge support that Turkey has given to Egyptian opponents, in the context of permits and legal stay and also defending them diplomatically many times.

“Others, like myself, don't exclude being asked to leave,” he adds.

When the news broke, Omar, who prefers to use his first name for security reasons, sent through a tweet from prominent opposition member and former Egyptian presidential candidate Ayman Nour, which is taken from a famous Egyptian proverb:

It gets narrower

Then,

Narrower

Then

Narrower

Then

It gets better

Things were getting worse and worse for Egyptians. “Give glad tidings to the patient ones,” Ayman added at the end, quoting from the Quran.

Roughly 3,000 of the 33,000 Egyptians living in Turkey are on humanitarian visas, which are issued mainly to people who have left Egypt for political reasons - for example charges were brought against them for peacefully protesting or they were arrested and tortured for opposing the current regime.

These visas are renewed every one to two years, and there is a widespread fear that once the time comes to reapply, they will simply be refused, or their requests left pending.

“This procedural cycle is very stressful,” said Hussein Saleh Ammar, a lawyer who lives in Turkey and represents several Egyptians living there.

“It makes the holders of this residency not feel stable and always feeling anxious and afraid. They face problems with each renewal and whilst they are waiting for it to be renewed, they cannot complete anything official.”

Egyptians living in Turkey without a stable legal status, or second nationality, are scrambling around for alternatives because they believe the net is closing in on them.

But for many, getting the necessary papers they need to go abroad has been close to impossible due to the hostility of the Egyptian embassy.

Egypt classifies Turkey as the centre of the opposition abroad and regularly refuses to issue official papers or renew documents, including passports, to the people living there. If they can, Egyptians travel to other countries in the region, such as Qatar, just to complete their paperwork.

In September, Amr went to the Egyptian consulate in Istanbul for his tawkeel, or power of attorney, which should have been a straightforward transaction. Once there, he was asked by the consulate staff whether he had “political problems” back home and was then accused by staff inside of forging his passport.

He was told bluntly: “We can’t help you with your documents, it’s not like you are a citizen, you can’t deal with us.”

The incident shook Amr, who questioned what it is he should do if he needs something from his country’s embassy.

“The Egyptian embassy in Turkey doesn’t give any consulate services to most Egyptians here, they don’t issue documents or papers, even for newborns seeking birth certificates, they say go to Egypt and get it issued from there,” he said.

“The embassy knows very well that most Egyptians living in Turkey are dissidents, that’s why they are doing this. I have friends in other Arab countries or foreign countries who don’t have these problems. The consulate here is obstinate in issuing official papers to Egyptians.”

'Painful situation'

Amr is not even on a humanitarian visa, simply a tourist one, which has already expired, and he is currently waiting to see if it will be renewed.

He has been trying to reach Europe, where his wife lives, for some time now. However, the Egyptian consulate has refused to issue his marriage certificate and therefore his visa keeps getting rejected.

This has created huge problems for many Egyptians living in Turkey, who struggle to get married, and because they do not have identification papers, cannot work legally or obtain insurance.

Ammar, the lawyer, explains that it is not even possible to be granted asylum in Turkey - it is only a temporary protection country.

If someone does seek asylum there, they could wait up to five years until the UN refugee agency sends them to a country that accepts them. Whilst their applications are processed, they are sent all over the country, outside the big cities like Ankara and Istanbul.

“It is a painful situation and does not create stability,” said Ammar. “Marriage, mobility, travel, movement – they are deprived of all these rights because they paid the price for a position they took, or because of political, human rights or social activity, or they only expressed their opinion and participated in demonstrations or a peaceful sit-in in Egypt that resulted in an unstable life.”

TV warning

Egyptians who fear being asked to leave - or worse, deported - have pointed out that Kuwait, Germany, Spain and Malaysia have all deported dissident Egyptians back to Cairo.

In his flagship programme, pro-government anchor Ahmed Moussa recently announced that Egypt has demanded Qatar send 220 members of the opposition, who he describes as “terrorists,” back to Cairo, as part of talks with Doha.

“Soon [Turkish President Recep Tayyip] Erdogan will invite Sisi to visit Turkey so the opposition there must search for a new place of refuge,” he added.

Moussa’s warning has been interpreted by some members of the Egyptian opposition abroad as an attempt to scare them into silence, but has at the same time compounded their fears.

According to Ammar, the issue of Turkey deporting Egyptians who face persecution at home has so far been a red line, however some have pointed to the case of Mohamed Abdelhafiz as an example of what could happen to them.

In January 2019, Abdelhafiz was detained at Istanbul Ataturk Airport, where he was planning to seek asylum, handcuffed, and deported to Egypt by Turkish authorities.

An agricultural engineer, Abdelhafiz was sentenced to death in absentia in July 2017 in a mass trial of 68 people in Egypt for the assassination of former prosecutor general Hisham Barakat in 2015.

Nine of his co-defendants were executed in February 2019, despite what Human Rights Watch has said are allegations about their torture and disappearance, which were not investigated.

When relatives finally located Abdelhafiz on 3 March that year he was at a court hearing. A lawyer present said that he was unable to see and hear properly and that it was possible he had been badly abused.

At the time of Abdelhafiz’s deportation, the case whipped up a media storm in Turkey and huge campaigns called on Turkish authorities to explain their behaviour.

According to Ammar, who is the legal representative for Abdelhafiz’s family, this is an exceptional case: Turkey officially apologised and the interior ministry dismissed the five police officers involved in his deportation.

“Of course, for any family, nothing can compensate for the loss of one of their children in this brutal way,” said Ammar.

'National security'

Some analysts have questioned if the move to mend the strained relations between Ankara and Cairo could actually benefit Egypt’s political prisoners.

Shortly after the 2013 coup, Egypt designated the Muslim Brotherhood, to whom Morsi was affiliated, as “terrorists” and used it as a pretext to imprison thousands of people on charges of belonging to the group.

Top leaders were thrown in jail, but also Christians, politicians and journalists who had openly criticised the Brotherhood.

Turkey’s foreign minister has said that Ankara is against the Muslim Brotherhood being classed as “terrorists”. However, it seems unlikely they will have much say in removing the label.

“The state considers it part of national security in which no other party should participate," said Omar.

With nowhere to turn, dozens of Egyptians have dived into social media and taken part in workshops on the Clubhouse app, alongside human rights activists, where they have been able to glean information and swap advice on which countries are best to go to beyond Turkey.

They have picked up tips on the asylum process, how to prepare applications, and which authorities to communicate with.

Three young Egyptians with political charges against them in Egypt have already arrived in the Netherlands where they have applied for asylum, according to Ammar. One of them told him that her father was killed by police in Egypt after he was arrested. Others search for more clandestine routes to take.

“I think in the coming days many young Egyptians will arrive in Europe, and they will seek asylum,” said Ammar.

'I would die from torture'

They won't just go to Europe. The family of Egyptian asylum seeker and outspoken social media influencer Aly Hussin Mahdy, who lives in the United States, were arrested earlier this year after a series of videos he posted online speaking out about human rights abuses in Egypt went viral.

Mahdy has addressed the Egypt-Turkey rapprochement on his popular YouTube channel and in response has been contacted by several Egyptians living in Turkey who are now scared and want his advice on getting to the US.

To discredit him, what is known as Egyptian “intelligence” media - news articles that are circulated in Egypt but have no traceable source - has accused Mahdy of taking $100,000 from young Egyptians in exchange for helping them with papers to get to the US.

Omar has also been approached by young Egyptians who have asked for help to either legalise their status or to travel outside Egypt.

He has offered to mediate with the authorities back home for their safe return, but this is only for Egyptians who are not high-profile critics and have not been outspoken in the media. None of these cases have yet been accepted by Egypt.

In the meantime, on the streets of Istanbul, fear is growing. When Amr was at the Egyptian consulate last March, he filmed what happened and posted it on social media, which drew the ire of authorities back home.

“You can imagine if I was treated like that in the consulate here in a foreign country what will happen to me if I go to Egypt," he said. "I would die from torture if I’m forced to return.”

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].