9/11 attacks 20 years on: How the 'war on terror' turned full circle

It was the early hours of the morning by the time I reached the banks of the Panj, the river that marks Tajikistan’s southern border. It was shivering cold, and dark.

The Tajik border guards had been good natured, but they had also been drunk and had gone about their business slowly. The Russians at the post further down the rutted track - the real border guards - were less drunk, but also more serious, and equally slow.

The ferry across the river was a flat barge with a tractor engine bolted in its middle. It was propelled by means of a winch attached to the engine, through which passed an enormous hawser. Either end of this thick rope was moored on the opposite banks of the Panj. We were tugged slowly across to Afghanistan.

The ferry halted with a bump and I stepped onto land. There was no light whatsoever. I am not sure that I had ever experienced such darkness.

On my back was a 65-litre rucksack containing a sleeping bag and liner, clothes, provisions and cooking equipment. Strapped to my chest was a bag holding a satellite phone and laptop. In each hand I clutched large and cumbersome containers of clean water.

Not for the first time - and not for the last - I found myself in a place where I knew nothing, and nowhere, and nobody; places like Murmansk, Bulawayo, Baghdad. All these places, and many more visited during my reporting career, had been bewildering at first.

I would be expected to quickly make sense of what was happening around me, and to then package up that understanding into stories for a newspaper in London.

But this was different to previous assignments, as tricky as some had been. I had stepped into an area of the country with few proper roads and no sign-posts; no electricity and no running water. It was terribly strange, this land in which I was about to work.

And I was not just standing in a strange land. I was living and attempting to work in a world that had changed, utterly.

Almost 7,000 miles to the west, the remains of the Twin Towers were still smouldering. The death toll of the 9/11 attacks was as yet unknown. In Washington, US President George W Bush was already talking about “the war on terror” and proclaiming that there had been “an old poster out West… that says: ‘Wanted: Dead or Alive.’”

The "forever wars" were about to begin.

From Nottingham to New York

Like most news reporters, I am reluctant to write about myself. In almost 40 years of journalism, I can count the times I have used the personal pronoun “I” on one hand.

It is my job to observe other people, to ask questions of other people, to record what others are saying and doing, or not doing. But like many people around the world, my life has a before 9/11, and an after 9/11.

As the 20th anniversary approaches, I’ve been talking with friends and colleagues about my experiences on that day and during the months and years that followed. I've been thinking about how my eyes were opened by the discoveries I made after 9/11.

In time, I came to understand that these abuses were not an aberration: when states believe they are under threat, many will quietly rip up the rule books they claim to respect

Initially, I was drawn to reporting on the human rights abuses that were being perpetrated by western governments because I saw them as being an aberration (and journalists do love the aberrational - there’s an old newsroom adage: dog bites man is of no interest; man bites dog is news).

In time, I came to understand that these abuses were not an aberration: when states believe they are under threat, many will quietly rip up the rule books they claim to respect. The gloves will come off. And then some governments will do whatever they can to conceal their crimes.

In 2001, I was chief reporter of the London Times. At 2pm on Tuesday 11 September I was sitting in court in Nottingham, in the English Midlands, waiting for a trial to begin.

It was actually a retrial: the defendant had already been convicted of bludgeoning a mother and her six-year-old daughter to death with a hammer as they walked along a country lane, and leaving another daughter, aged nine, for dead. The court of appeal had ordered a retrial. It seemed like a pretty big story.

A few minutes after 2pm - shortly after 9am in New York - a colleague from the London Evening Standard tapped me on the shoulder: “Your news desk wants to speak to you.” This reporter had been contacted on his mobile telephone, which could be placed on silent, and vibrated when called: quite an innovation at that time.

A news editor in London told me that two aircraft had flown into the World Trade Center. They asked me to get to Heathrow airport as quickly as possible. I ran to my hotel, checked out, rushed to a nearby car park, and set off.

On the motorway, I called a friend in New York on my hands-free phone. He told me that a third aircraft had just been flown into the Pentagon.

I made it from Nottingham to Heathrow, 130 miles away, in a little over 90 minutes, sometimes driving dangerously quickly.

It had not occurred to me that all flights would be grounded. I found myself stranded at Heathrow for – what was it – a day? Two days? (I later learned that one aircraft, a DC-10, did cross the Atlantic at that time. This discovery, which came years later, was to be very important to my work.)

Eventually, flights resumed to Toronto. By the time I boarded one, I was already thinking that I was going the wrong way: that if I wanted to understand what had happened, and report on what would be happening next, I should be travelling east, perhaps initially to Islamabad.

There were no flights from Toronto to New York, and no trains either. I walked out of Union Station in the heart of the Canadian city, approached the first taxi on the rank and asked the driver if he would take me to New York, a 500-mile journey.

Without batting an eyelid, he said yes. We agreed a price, and he said he would need to go home to pick up his passport. As we approached his home, he seemed a little unsettled, and I asked him if everything was okay.

“None of my passengers have ever seen my home before,” he explained. He lived in a mansion.

We drove through the night, crossing the border at Niagara, and by dawn I was at Ground Zero.

As appalling as the death toll was (eventually it was established that 2,996 people had been murdered), many assumed at the time that it would be even higher: the British ambassador talked of expecting the British dead alone to number several thousand.

But few people were grieving for their loved ones in those first days. They didn't know where they were: in many cases, their brothers, wives, sons and daughters remained unaccounted for. They appeared simply to have vanished.

On every wall and window in the city there were pictures of missing friends and relatives, along with mobile phone numbers and appeals for information. There was a clear sense of mourning, however: for the loss of America’s invulnerability. The people were jittery, hollow-eyed, exhausted. The city was at the centre of an epidemic of trauma. And hanging over it was a lingering stench; New York City smelt like hot brakes.

Travelling east

After working in New York for a few weeks, I went east.

First to Moscow, where I picked up a visa to enter Tajikistan. Then south to Dushanbe, Tajikistan's capital, where a smart young student helped me secure permission to join a supply convoy that was about to be dispatched into Afghanistan by the Taliban’s opponents, the United Islamic Front for the Salvation of Afghanistan - the so-called Northern Alliance.

It was agreed - with the assistance of a few dollars - that I would cross the Panj river with the convoy, and then go my own way. And so I found myself standing on the south side of the river, in the dark, with a handful of small buildings dimly visible in the gloom. I was anxious, and excited.

I was confident that I would soon be approached by somebody offering to work for me: it was the sort of place where translators and fixers and drivers would hang out, looking for journalists who were entering the country.

Not long after climbing off the ferry a young man walked over and asked, in perfect English, whether I needed a translator and guide. His name was Farid. I was soon to discover that Farid was clever, good-humoured and resourceful, and I couldn’t have done my job without him.

He and I worked together for several weeks in northern Afghanistan, based initially at Khwaja Bahauddin, the rugged and dusty town where Ahmad Shah Massoud, the so-called Lion of Panjshir, had been assassinated by al-Qaeda two days before 9/11. For a while we were joined by Times photographer Pete Nicholls, whose photos illustrate this story.

Farid was so proud of having come from the Panjshir Valley, the land that neither the Soviets nor the Taliban had tamed.

We travelled to Taloqan and Kunduz, reporting on fighting between the Taliban and the Northern Alliance.

At a time and place when there were no landlines or mobiles, Farid attempted to keep in touch with his family in the Panjshir by giving spoken messages to truck drivers, who would pass them on to other drivers, in the hope that they would reach his home village. It seemed to be a remarkably efficient way of communicating news.

I have so many vivid memories of Afghanistan at that time: the beaten paths that showed the safe passage through minefields; the communal bathhouses and the blind men singing for their suppers; the surgeon at a field hospital - the only clean-shaven man I had seen in Afghanistan by this time - boiling his instruments in stainless steel pans ahead of a battle; the way in which the fizz of an incoming shell seemed to fill the air in front of me; the shallow trench into which I leapt, landing painfully on my knees.

It was an extraordinarily dangerous place to be a journalist. One day I chatted at a roadside cafe with a German journalist, Volker Handloik. The following day he was killed, along with two other journalists, shot while apparently riding on the outside of a Northern Alliance armoured vehicle.

The steady collapse of the Taliban often resulted in a return to the lawlessness that the movement had done much to ruthlessly stamp out. The Taliban would retreat from a town, there would be a few days of peace and quiet, and then armed robbers would emerge onto the unlit streets at night.

Ten days after the death of Volker, while at the frontline, I met a Swedish TV cameraman, Ulf Stroemberg. He seemed to be thoughtful and gentle man.

A night or two after this, while walking through Taloqan, I was threatened by a small group of boys, aged around 15, armed with Kalashnikovs. The English-speaking imam with whom I was walking bundled me into a nearby mosque, and explained that they had been demanding I hand over my warm hat. He made it clear that had I been in danger of being shot.

The boys appear to have then gone to a house where four Swedish journalists were lodging. They robbed two at gunpoint, and shot dead a third: Ulf Stroemberg.

As dangerous as it was being a journalist in Afghanistan at that time, it was so much more perilous to be an Afghan civilian: according to one study, by the end of the year between around 1,000 and 1,300 had been killed in air strikes alone.

When I had returned to the clean-shaven surgeon’s tented operating theatre, he was patching up members of a family injured by a shell that had landed beside the road ahead of me. One member of the family lay groaning on a bed. He looked as though he had been mauled by a lion.

The corpse of a second lay on an operating table, covered by a blanket. A boy of eight or nine with a blank expression stood beside the table. His hand was hidden under the blanket, where he held the dead man’s hand.

Initially, the Taliban were not a powerless force. They possessed artillery and armour, but the arrival of US and UK air power dramatically altered the balance, and a succession of easy targets were soon being picked off.

A boy of eight or nine with a blank expression stood beside the table. His hand was hidden under the blanket, where he held the dead man’s hand

With Farid’s help, I came to understand how war in Afghanistan traditionally involved negotiation, bribery and trade, as well as violence. I could see how much time these enemies on the ground spent talking to each other by hand-held radio - doing deals as well as doing battle.

Once, on the frontline near Kunduz, I watched the two sides agree a prisoner-for-bodies deal by walkie-talkie: the Taliban wanted the return of prisoners - fighters captured during a recent assault on a nearby village - while the Northern Alliance wanted to recover a number of corpses lying in no-man’s land, in a valley between two bare, dusty hills.

Eventually, an exchange rate was agreed: three bodies would be handed over for each live prisoner.

Over the radio, the Taliban commander informed his Alliance counterpart that they could see there was a foreigner with them, and asked that he ensure there were no attacks from the air during the exchange. He was told that the man he could see through his binoculars was a journalist from London, who had no control whatsoever over the air strikes.

The Alliance sent forward an ancient blue Russian truck with four prisoners huddled in the back, their elbows tethered behind their backs.

A little while later the truck returned, and we jumped up to count the corpses in the back. There were nine. I didn’t need Farid to translate the angry comments from those around me: “They’ve ripped us off.”

Nobody left to fight

At the end of the year, British special forces posted to the Asamayi mountains overlooking Kabul were dismayed to realise that the world’s media had got there before them. One of them, a friend, later explained the disappointment: “It couldn’t have been that bloody dangerous if the press were already there.”

When the first British troops drove into the city, late at night, the only fighting they saw was a punch-up in the street between two British newspaper photographers competing over the best place to picture the great arrival.

By January, the caves of Tora Bora appeared to have been cleared of the last few Taliban and al-Qaeda fighters. Later, roaming around the east of the country, the UK’s Royal Marines discovered that there was nobody left to fight.

I was in Kabul, where there appeared to be a widespread sense of relief that the Taliban had gone. Despite sleeping on the floor, I was enjoying the comfort of a rented house. A relaxed calm appeared to have settled over the city.

My translator in the Afghan capital was the son of a man who had been a senior officer in the KHAD, the secret police during the days of Soviet occupation: an extraordinarily well-connected man.

At this time there were receptions at the newly-reopened British embassy, football matches at the Ghazi stadium, where the Taliban had once carried out executions and amputations, and Kabul’s buzkashi players competed against teams from the Pansjhir Valley.

I had never seen such a confusing, violent and ultimately thrilling game.

As the US and UK air strikes began, Bush had acknowledged the need to establish a strong government in Kabul, and pledges of aid began to be made by governments around the world. Not all of it materialised.

By early 2002, the White House was won over to the idea of nation-building. Despite his recent claims to the contrary, one of the most enthusiastic early champions of this project was the then-senator Joe Biden.

Outside Kabul, there continued to be chaos and serious crime. There had been more than two decades of continuous warfare; complex social, political and ethnic conflict, fuelled by superpowers and ruthless regional neighbours: many Kabulis assumed it would not be long before the fighting began again.

These were not security measures: these men were being subjected to sensory deprivation

Some would talk about the coming spring offensive. Why do you believe there will be a spring offensive, I would ask. “Because this is Afghanistan,” they would reply. “There is always a spring offensive.”

I had much to learn, not only about the old realities of life and death in Afghanistan, but also about the true character of the nascent “war on terror”.

One day during that winter in Kabul I called in to the newly reopened office of a major international non-governmental organisation. There, a senior official calmly informed me that the Americans had begun torturing their prisoners at a detention facility at Kandahar.

I was appalled. Surely the Americans wouldn’t stoop to torture, notwithstanding the enormity of the crimes committed on 9/11? How did he know, I asked?

The Red Cross had been inside, he explained, interviewed prisoners, and the accounts they gave of the abuses they had suffered corroborated each other. There was a pattern. This was such an extraordinary allegation that I believed I needed a second source. I looked pretty hard for that second source, but could not find it.

Had I known then what I know now, I would have realised that the second source had been staring me in the face for days. On 11 January, when the first jump-suited prisoners had been dragged across the ground at Camp X-Ray, at Guantanamo Bay, they were photographed by a US Navy photographer, Shane McCoy.

Five of McCoy’s photographs were then made available to the Associated Press news agency.

Those pictures showed that all the prisoners were wearing masks over their mouths, blackened goggles, ear defenders and thick black mittens. These were not security measures: these men were being subjected to sensory deprivation.

The US military had documented its own use of torture, and then distributed the evidence across the globe. But like most of the rest of the world, I just did not know enough about these matters to be able to understand the significance of what I was seeing. I did not at that time understand that I was looking at photographs of men being tortured.

In March, the honeymoon began to come to an end. The fighting in Afghanistan flared up again, just as people in Kabul had predicted. There were clashes between US troops and Taliban and al-Qaeda forces near Gardez in the south-east of the country, a few miles from the border with Pakistan.

But by then, everyone’s attention had turned elsewhere. Toppling the Taliban had appeared to be easy, and an altogether insufficient response to the horrors of 9/11. Bush, Tony Blair, the Pentagon, the world’s media: we were all looking to Iraq. We were all preparing for the next campaign of the forever wars.

Invading Iraq

Later that year, after a spell reporting from the West Bank and Gaza, and - a blissful break - covering the football World Cup in Japan, I was dispatched to Iraq, to prepare for the invasion.

It was my first visit to the country since 1998, when I had driven across the Western Desert to report on the four-day bombing campaign that the US and UK had mounted against targets across the country.

The justification given for those attacks had been Saddam Hussein’s failure to co-operate with United Nations inspectors searching for his weapons of mass destruction. It had been an interesting experience, being on the receiving end of the largesse of the Royal Air Force.

Here we were again, in 2002, with the British government claiming that its intelligence showed “beyond doubt” that Saddam was producing chemical and biological weapons.

I flew in from Amman and spent several weeks travelling around the country, working again with Pete Nicholls, reporting on the way in which people were bracing themselves for the inevitable.

Like all journalists visiting Baathist Iraq, we were assigned a Ministry of Information minder, an English-speaking secret policeman who accompanied us everywhere we went, and who wrote a report on our activities every evening.

Each day, as our hotel rooms were being serviced, they were carefully searched by a government official (I know this because one enterprising British journalist covertly filmed the searches).

One evening, when eating fish at an open-air restaurant on the banks of the Tigris, my minder leaned in towards me and whispered: “You know Ian, there is no WMD. There was. But there isn’t now. Trust me, I know.”

I didn’t trust him. He was, after all, spying on me. Moreover, I could not readily accept that Saddam would give the UN the run-around - to the point of triggering an invasion by the United States and its allies - in order to conceal what he did not possess, rather than what he did.

Not for the first time, and not for the last, I was completely wrong.

During 2002, I never accepted the UK government claim, made throughout the year, that no decision had been made about whether to go to war with Iraq. That beggared belief.

But I confess that, perhaps to my discredit, I wanted to get it over with. Not because I believed Saddam’s regime to be evil (although I did); nor because I believed he still posed a threat to regional security. Put simply, I was certain we were going to war, come what may, and I knew that I would be expected to report on that war. I wanted to get that task behind me.

A few months later I was entering Iraq again, this time from Kuwait, where the hotels had seemed to be fairly teeming with thousands of burly American construction workers, waiting to move north to help rebuild the country.

Not for the first time, and not for the last, I was completely wrong

I crossed the border in the wake of British troops who were fighting their way into Basra.

At Saddam’s palace on the banks of the Shatt al-Arab I came across a line of Iraqi prisoners, kneeling bolt upright in the sun, with hoods over their heads and their hands tied with plastic handcuffs behind their backs.

A few hours later I returned and the prisoners were still there, still kneeling, upright and hooded, under the hot sun.

A couple of British army medics sidled up to me and confided that they had just revived a prisoner who was being interrogated by special forces troops in the basement of a building in the city.

There were a number of prisoners down there, they said, and the place smelled of urine, blood and vomit. This was nothing like the prisoner-handling operations I had witnessed on the Saudi-Kuwaiti border during the war of 1991.

Back then, British soldiers had taken good care of their Iraqi prisoners, who were traumatised and bedraggled after weeks of aerial bombardment. They had given them water and shelter, and allowed them to smoke before moving them on.

Now, British soldiers and marines were taking over primary schools in Basra, using them as bases. Outside a number of these schools, queues of men carrying buckets and bottles began to form.

They explained to me that the electricity supply had failed and there was no running water. “It wasn’t like this in ’91 or ’98,” one explained. “It wasn’t even like this when we were fighting them,” he said, pointing towards Iran.

The British, of course, had a plentiful supply of electricity from their generators. I went to see an officer responsible for logistics and supplies, and explained what was going on outside his base.

He made clear that his unit’s task had been to drive out the Iraqi army and Baathist militia. That job had been completed. “We might be home by April,” he said, cheerily.

The city began to be overwhelmed by armies of looters, many of them young boys, who were stripping away any piece of metal or wiring they could find - hence the electricity black-outs.

With no police or prisons to help them, overwhelmed British soldiers adopted a policy they called “wetting”: tossing looters into the Shatt al-Arab, so that they would have to go home, change into dry clothes, and stop stealing for a while. Inevitably, a number of boys drowned.

The burly construction contractors who had been lounging around the five-star hotels of Kuwait City were nowhere to be seen.

War correspondents can be curiously blinkered people. Often, they can report only on what they see: the so-called “big picture” is an elusive thing, frequently more accessible to people watching from afar.

So, when the editor of the Times called on my satellite phone, to ask how the campaign seemed to be going, I replied: “Well, judging by what I see happening in front of me, I must say that I don’t think it’s going very well at all.”

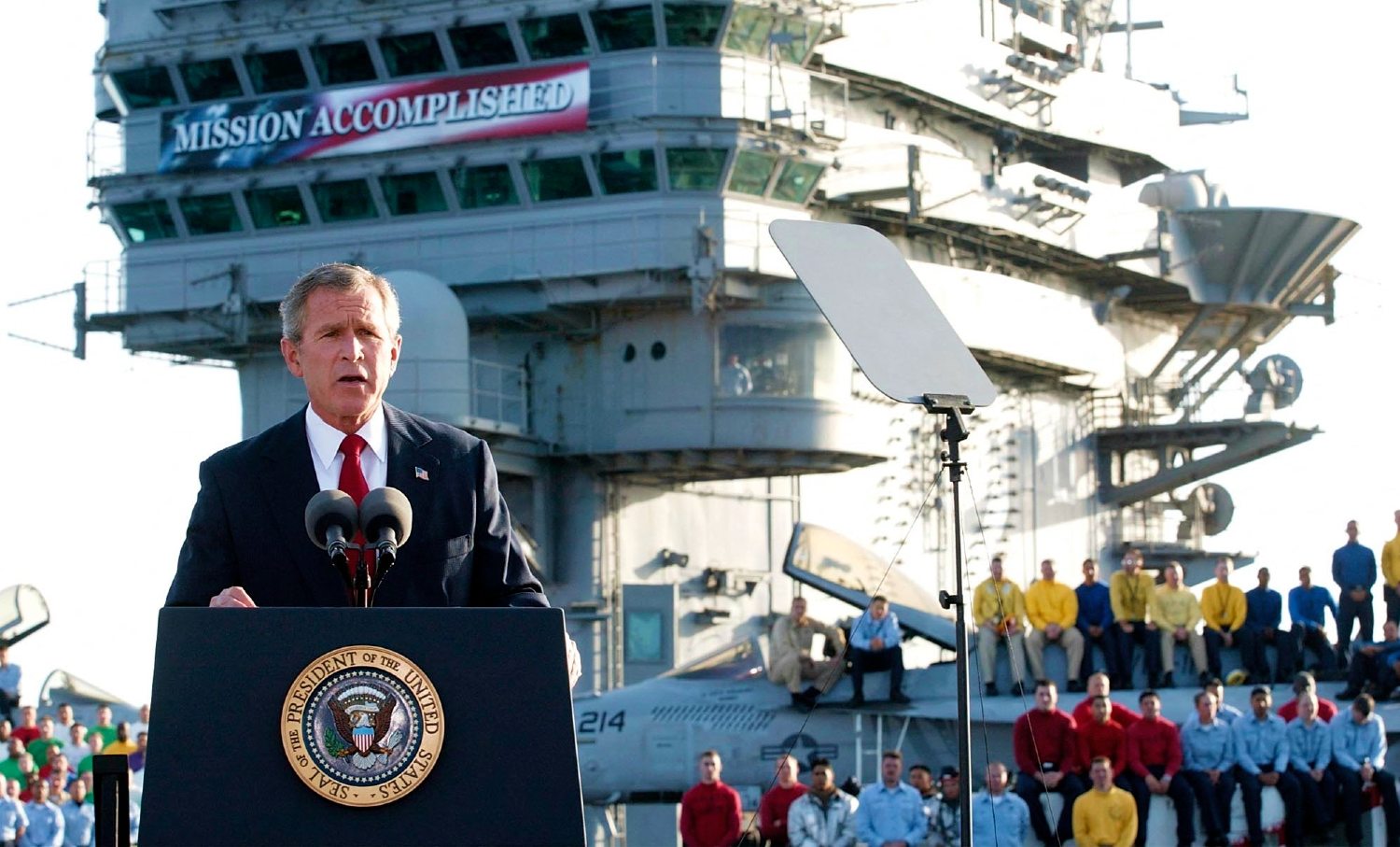

On 1 May 2003, President Bush was flown to the USS Abraham Lincoln, where he gave a speech in which he declared that the Taliban had been “destroyed” and that major combat operations in Iraq were also over.

“In the battle of Iraq, the United States and our allies have prevailed,” he said. The sailors and airmen whooped and clapped. Behind him, an enormous banner read: “Mission Accomplished.”

The speech had taken place just off the coast of San Diego, thousands of miles from the Middle East.

Exposing rendition

In 2005, after a spell as news editor at the Times, I joined the Guardian, in order to return to reporting. On my first day in this new job, I rang a friend in Washington DC, to give him my new email address.

“Have you read the front page of today’s New York Times?” asked Bill.

The newspaper had established that the CIA had created a series of front companies in North Carolina. Through these companies it owned a number of executive jets, which were picking up prisoners in central Asia and the Middle East, and flying them to secret prisons around the world. The rendition flights.

“If they’re flying from North Carolina to the Middle East, they’ll need to refuel somewhere,” said Bill. “And where do you think that might be, Ian?”

He was right. Eventually, by tracking the tail numbers of the aircraft, I was able to show that the CIA had flown in and out of the UK at least 210 times in the four years since 9/11, using 19 different airports and RAF bases.

The agency denied that there was ever a detainee on board when they flew in and out of the UK, and no evidence has emerged to contradict this.

The same could not be said of the US base on Diego Garcia, an island of the British Indian Ocean Territory, where detainees were transited and, allegedly, held.

By now, the US media had been steadily peeling back the secrecy surrounding the rendition and mistreatment of terrorism suspects - or kidnap and torture, to use plain English - delving deep into the subject matter of the scoop that I had missed in Kabul, in January 2002.

At the end of the year there were two significant moments in the UK. First, the Appellate Committee of the House of Lords - at that time the country’s supreme court - ruled that lower courts could not consider evidence that may have been extracted under torture. The government had contended that an immigration appeals commission could consider such evidence.

“The English common law has regarded torture and its fruits with abhorrence for over 500 years,” thundered the senior judge, Lord Bingham.

However, the Lords’ judgment did not prevent government ministers using such material in other ways. Indeed, one judge, Lord Brown, said that not only was the government entitled to use what he described as “the fruit of the poisoned tree”, it had a responsibility to do so if this were required in the interests of state security.

This, I was beginning to learn, was a freedom that the British state was not hesitating to exercise.

Five days after the Lords’ judgment was handed down the foreign secretary, Jack Straw, gave evidence to the Foreign Affairs Committee of the House of Commons.

Asked about the CIA’s use of UK airports and allegations about the UK’s involvement in the rendition programme, he replied:

“Unless we all start to believe in conspiracy theories and that the officials are lying, that I am lying, that behind this there is some kind of secret state which is in league with some dark forces in the United States, and also let me say, we believe that Secretary [Condoleezza] Rice is lying, there simply is no truth in the claims that the United Kingdom has been involved in rendition full stop, because we have not been.”

Straw must have been very confident that the true facts would not subsequently emerge.

The following year the UK Parliament’s Intelligence and Security Committee (ISC), which was supposed to provide oversight of the country’s intelligence agencies, began looking at the matter.

After conducting a number of secret hearings, the ISC concluded in July 2007 that the UK intelligence agencies MI5 and MI6 had been guilty only of being “slow to detect the emerging pattern” of CIA rendition operations.

This too would eventually be shown to be completely untrue. But for the next few years, MI5 and MI6 officers would point to the ISC report, and tell journalists: “We’ve been given a clean bill of health.”

Basra and Helmand

In southern Iraq, meanwhile, the British began to face a determined, well-armed and apparently unanticipated insurgency, led by the Shia scholar Muqtada al-Sadr.

The British had already alienated much of the population of Basra. Now, in their desperation to gather intelligence about Sadr’s Mahdi Army, they resorted to brutal interrogations. The Red Cross and British army lawyers raised the alarm, but a number of people died in British military custody.

A public inquiry would later establish that one, a hotel receptionist called Baha Mousa, had suffered 93 separate injuries before dying after 36 hours of interrogation.

A senior military intelligence officer told the inquiry that the Americans had thought British interrogation methods were too mild and not producing results.

In early 2007, with the onslaught of mortar and sniper attacks and roadside bombings intensifying, the rules of engagement were rewritten: British troops in Basra were instructed to shoot any civilian who was seen carrying a mobile phone or a shovel, or acting suspiciously.

Eventually the British would do a deal with the militias, releasing prisoners in return for a cessation of attacks on their bases. Then they retreated to an airport on the outskirts of the city.

In London, defence officials were whispering quietly about whether they could publicly use the term “strategic defeat” when discussing Iraq. In Afghanistan, the war was not going much better.

In early 2005, Nato decided to expand its Afghanistan commitment. By that time, there had been a sense among ministers in Tony Blair’s government and among officials at the Ministry of Defence (MoD), that the UK had been “punching below its weight” in the country. Senior army officers, meanwhile, were eager to put the failures of Iraq behind them with a new campaign.

The fact that British defence planning assumed that the country could not fight two wars at once was deliberately overlooked.

Following a British official inquiry into the war in Iraq, its chair Sir John Chilcot, a former senior civil servant, would report: “In deciding to undertake concurrent operations in Iraq and Afghanistan, the UK knowingly exceeded the Defence Planning Assumptions. All resources from that point onwards were going to be stretched.”

The MoD told Chilcot it could not explain this decision, a response he condemned as “unacceptable”.

Despite knowing it lacked the resources, in April 2006, the British government announced it was going to expand reconstruction efforts in Helmand, in the south of Afghanistan, where almost half the country’s poppy crop was being grown.

The head of the army, Richard Dannatt, told the British ambassador in Kabul that if he did not send troops to Helmand, at a time when his forces in Iraq were being reduced and operations in Northern Ireland were winding down, the army would be cut in size. “It’s use them or lose them,” he reportedly said.

A force of 3,300 troops was assembled. One of the officers who led them told me: “The Canadians had got Kandahar, and the thinking at the MoD [in London] seemed to be: ‘We should have got Kandahar.’

“So, we decided to go to Helmand instead, and after the decision was taken to go there,” – after, mind – “Downing Street decided that the reason we were going was poppy-eradication.

“We took one look around and decided there was not going to be any poppy eradication on our watch. If we’d taken these people’s livelihoods away from them, that would definitely fuel an insurgency. But we started getting shot at anyway, not long after we arrived.”

The battle group was assembled around soldiers of a battalion of the Parachute Regiment, a unit whose training and culture prizes aggression, perhaps more than any other in the British army.

Those shooting at them were always described as Taliban - “Terry Taliban,” in the argot of the young soldiers - overlooking completely the complex relationships and rivalries among the groups they were fighting.

Before long, the “reconstruction efforts” were marked by a series of violent encounters. The body count started to mount, not least among Afghans.

Guantanamo and torture

Back in London, litigation brought on behalf of a UK resident incarcerated in Guantanamo, Binyam Mohamed, began to provide a glimpse at how closely embroiled in the rendition programme the UK’s intelligence agencies had become.

The court heard that MI5 had sent an officer to Karachi after the CIA had informed the agency of the way in which it was severely mistreating Mohamed, and how he was responding. MI5 and MI6 subsequently travelled to Guantanamo to interview Mohamed, and many other prisoners.

The courts ruled that MI5 had gone “far beyond that of a bystander or witness to the alleged wrongdoing”.

The British government, meanwhile, was increasingly concerned about the threat posed by al-Qaeda terrorists. Two of the four suicide bombers who murdered 52 people and injured 700 on London’s transport networks in July 2005 had recorded videos in which they explicitly said they had carried out the attacks because of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq.

During two separate terrorism trials in London and Manchester, defendants who had been detained in Pakistan before being deported to the UK alleged that they had been repeatedly tortured, and that MI5 and MI6 officers had visited them between torture sessions, asking the same questions that had just been put to them by their Pakistani tormentors.

One of these men, Rangzieb Ahmed - who is now serving a life sentence - lost three of his fingernails after MI5 and police in Manchester drew up a list of questions for him, which MI6 had passed on to Pakistan’s notorious Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) agency.

When the agencies were called upon to address these allegations, the courts were cleared of the press and public.

Counter-terrorism detectives were so sensitive about the Ahmed case that one of them rang me, told me that I should not report that Ahmed had been tortured, and threatened that if I did, he would harm me, in some undefined way.

There were more cases, in Egypt and Dubai. Once again, I was initially reluctant to believe that the UK’s intelligence and security agencies were operating under a government policy that allowed them to be complicit in torture. But a clear pattern was emerging.

I travelled to Pakistan and Bangladesh, and investigated still more. Sometimes local intelligence officers would confirm that the allegations of torture were true, and would talk of the immense pressure that they had been under from their US and British counterparts.

The British had been “breathing down our necks for information”, said one of the intelligence officers responsible for torturing a British-Pakistani medical student in Karachi in 2005.

The British government would never address the particulars of any allegation of involvement in torture. Instead, they fell back on a rather unconvincing mantra: “The British government unreservedly condemns the use of torture and its policy is not to participate in, encourage or condone the use of torture for any purpose.”

By 2009, as the cases piled up, the denial was looking rather threadbare. But it spurred me on. I was determined to bury it under a mountain of evidence.

I was surprised at how few of my fellow British journalists chose to pursue the allegation that the UK and its intelligence agencies were involved in the abuse of British citizens and others during this so-called war on terror.

There were, of course, a small number of honourable exceptions, such as Richard Norton-Taylor at the Guardian, David Rose at the Mail on Sunday and Stephen Grey, now at Reuters.

I assumed - but cannot be sure - that some editors were persuaded, over lunch, to ensure that their news organisations did not look too closely at the way in which the UK had become party to the US rendition operations.

At one point, the editor of the Guardian, Alan Rusbridger, contacted the ISC and suggested that it was not really good enough that these serious human rights abuses were being investigated only by journalists.

The ISC promised to look into the matter. Forty minutes later a representative of the committee called Alan back. “Erm, no," she said. “We won’t be looking at this, it’s not part of our remit.” Again, this was the opposite of the truth.

Digging deeper

I started to dig deeper. I found evidence that the claim that MI5 and MI6 had been guilty only of being “slow to detect the emerging pattern” of CIA rendition operations was utterly untrue.

The day after 9/11, the director-general of MI5, Eliza Manningham-Buller, Richard Dearlove, the chief of MI6, and Francis Richards, the head of GCHQ, flew to Washington aboard a DC-10. The UK's top spies were there to deliver a message: there would be full British solidarity.

By reading the memoirs of two former CIA officers, one of them its one-time director George Tenet, along with the diaries of Blair’s head of communications Alastair Campbell, and a speech by Manningham-Buller, it was possible to pick up the pieces of a jigsaw which, once assembled, told the truth.

Blair had somebody write back, denying that he had authorised acts of torture. Well, that was interesting: he had denied an allegation that I had not put to him, and evaded a question that I had

Four days after the lone trans-Atlantic flight, the CIA had sent a delegation to the British embassy in Washington to give a three-hour briefing to MI6 on the rendition programme that was about to be rolled out.

It was even possible to identify some of the CIA officers at the briefing. One of them was retired by the time I pieced this together and, to the amazement of my British eyes, was in the telephone book at his home in suburban Virginia.

I called. He picked up the phone. I introduced myself and asked whether he could give me the names of the MI6 officers who had been present at the briefing. To my further amazement, he told me. “One was Mark Allen. The other was that big Soviet expert – what’s his name?”

I had no idea. The UK isn’t like the US. Until a few short years ago, even the names of the heads of the agencies had been official secrets.

By mid-2009, it was possible to work out, through careful reading of the ISC’s annual reports, that when MI5 and MI6 officers interrogated prisoners who were at clear risk of being tortured, they were not acting without authority. They were operating in accordance with a carefully crafted guidance document. A sort of British government torture policy.

One ISC report made clear that Blair had been aware of this policy. I wrote to the former prime minister, asking whether he was aware that this policy had resulted in people being tortured, and asking whether he could tell me more about his role in the drafting of the policy.

Blair had somebody write back, denying that he had authorised acts of torture. Well, that was interesting: he had denied an allegation that I had not put to him, and evaded a question that I had.

I wrote again, asking Blair the same question. The former PM had his assistant write back again, saying he did not understand what I was asking him.

So I tried a third time, this time asking two lawyers - one with experience of working at the International Criminal Court in the Hague - to assist with the drafting of the letter.

Blair again had his assistant write back, denying that he had ever authorised acts of torture. The ducking and diving was highly illuminating, I thought.

In early 2011, the government began to disclose a series of hitherto-secret documents, after being sued by a group of British former Guantanamo inmates.

Government lawyers had dragged their feet for months, and then years, but eventually, under the disclosure rules applying to civil trials in the UK, they had to come up with some relevant material.

I applied to the court for copies, and was granted permission. What I received amounted to a car boot-load of paperwork, and the documents looked as though they had been shuffled. Sorting them took days.

Among them was a telegram that Jack Straw had sent to various government missions, ordering that British Muslims taken prisoner in Afghanistan after 9/11 should be consigned to Guantanamo.

The telegram had been sent in January 2002, during the week that Camp X-Ray opened for businesses, when Shane McCoy had taken his revealing photographs (and also during the same week that UK Defence Secretary Geoff Hoon had mobilised the part-time members of the armed forces who served as specialist interrogators in Afghanistan and Iraq).

Tony Blair, or people very close to him, appear to have taken a decision to take the gloves off in early January 2002.

Also hidden among my car boot-load of documents was the UK’s “torture policy”. There were several versions of this paper. The first had been issued in January 2002, after MI5 officers had witnessed Americans beating the living daylights out of prisoners at their newly-established base at Bagram, north of Kabul, and had asked London where they stood legally if they were to question the victims.

This first draft had been based upon an MoD document drawn up for members of the British military who might find themselves in a similar situation, watching allies torturing prisoners. Refined versions were drafted in 2004 and 2006, shortly before suspected British militants were about to be detained and tortured in Pakistan.

It was a truly remarkable document. It instructed senior intelligence officers to weigh the value of the information they were seeking against the degree of pain that the prisoner might be expected to suffer when it was being extracted.

It acknowledged that MI5 and MI6 could be in breach of both UK and international law when asking for information from prisoners held by overseas intelligence agencies known to use torture.

The policy document explained that government ministers were expected to be consulted in advance of any potentially criminal act, in order to obtain political cover.

Finally, it warned that the UK could be at greater risk of terrorist attacks if the public were to become aware that the document existed.

Common cause with Gaddafi

The UK general election of 2010 saw the formation of a Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition government. Labour was out of power after 13 years.

One of new Prime Minister David Cameron’s first steps was to announce the formation of a judge-led inquiry to examine the UK’s involvement in rendition and the mistreatment of detainees after 9/11.

Late the following year, the clearest possible evidence of that involvement came to light during the Libyan revolution.

Searching through the offices of Moussa Koussa, the country’s former intelligence chief, a researcher from Human Rights Watch discovered a treasure trove of hitherto secret documents that laid bare the ways in which the CIA and MI6 had hatched a number of operations that resulted in opponents of Muammar Gaddafi being kidnapped and handed over to him.

The victims had included a man and his pregnant wife, kidnapped in Bangkok in 2004, and a husband and wife and their four children, the youngest aged six, who were bundled aboard an aircraft in Hong Kong two weeks later.

They were all flown to Tripoli. In between the two operations, Blair paid his first visit to Libya, embraced Gaddafi, and said they had found common cause in the fight against terrorism.

While the women and children were released in due course, the men - Abdel Hakim Belhaj and Sami al-Saadi - spent years in Gaddafi’s prisons and were severely tortured.

Belhaj’s wife Fatima Boudchar told me how she had been taped, head-to-toe, to a stretcher for the 17-hour flight to Tripoli. Al-Saadi’s eldest daughter, Khadija, told how she saw her mother and father being hooded and their legs bound with wire when their plane landed.

Among the documents found by Human Rights Watch were signed faxes from Mark Allen, in which he reminded Koussa that MI6 had provided the intelligence that allowed the families to be kidnapped.

There were also lists of questions that MI5 and MI6 wanted to be put to the two men. The information extracted by Gaddafi’s torturers had then been used to justify the detention of Libyan dissidents living in the UK.

A police investigation was now inevitable. But when Scotland Yard detectives began making inquiries, the government suspended its judge-led inquiry, saying it could not continue at the same time as a police investigation.

The police spent more than three years investigating, with Jack Straw being interviewed as a witness. Finally, they handed their file over to the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS). There was a wealth of evidence against Allen, who by now was Sir Mark Allen, having been knighted the year after the kidnappings.

Nevertheless, government lawyers ruled that the evidence was not sufficient to bring charges. The victims and the investigating officers were appalled, and angry.

By now, several years after I had taken my deep dive into British state crimes, I was not in the slightest bit surprised. I would have been astonished if the CPS had recommended that Allen be charged.

After Sami al-Saadi and his family brought proceedings against the British government, the matter was settled out of court. The family was paid £2.2m, but the government did not admit liability.

Belhaj held out, however, saying he would settle for a nominal sum of £3, but only if the British government apologised to both him and Fatima. That apology finally came in 2018, from Theresa May, who was then prime minister.

The ISC, meanwhile, was finally conducting a genuine investigation into the UK’s involvement in kidnap and torture, under the chairmanship of Dominic Grieve, a widely respected former attorney general for England and Wales.

In June 2018, the ISC reported that it had been prevented from questioning witnesses and that documentation from some of the key periods was unaccountably missing. “Formal records are lacking for at least some of the period of concern,” the report noted.

Nevertheless, the committee said that in the nine years after 9/11, the UK’s intelligence agencies had supplied questions to overseas partners on at least 558 occasions, despite knowing or suspecting that a prisoner was being tortured; had been involved in 53 rendition operations - and had financed three of these - and that their officers were witnesses to torture or mistreatment on at least 13 occasions.

Far from the allegations of the UK’s involvement in rendition being a conspiracy theory - as Jack Straw had told Parliament in 2006 - the ISC found that Straw had personally authorised the payment of “a large share of the costs” of the rendition of two people in 2004.

It was not only MI5 and MI6 that had been involved in the abuses. The UK’s signals intelligence agency GCHQ, which for years had claimed to have a clean pair of hands, was shown to have helped the CIA locate people who were subsequently kidnapped and tortured.

And one short footnote in the ISC’s report showed that at the height of the Abu Ghraib scandal, the MoD had decided to send a team of British military interrogators to the prison.

Although the report was redacted before publication, it was possible to work out that the committee had established that in January 2002, an MI6 officer had watched as the CIA sealed one prisoner at Bagram, Ibn al-Sheikh al-Libi, inside a coffin, before flying him to Egypt.

The report says that MI5 subsequently provided questions to be put to Libi in Egypt. The responses he gave - falsely claiming that there had been a link between Saddam Hussein and al-Qaeda - were then used by the US and UK governments to help justify the 2003 invasion of Iraq.

The oft-used mantra that Her Majesty’s government “unreservedly condemns the use of torture” and does not participate in or condone torture was shown to be a hollow lie.

Broken bodies, shattered minds

In 2010, I had been a frequent visitor to the military wing of a hospital at Selly Oak in Birmingham, visiting a friend who had lost both legs to an improvised explosive device in Helmand.

In bed after bed inside the wing sat maimed young soldiers. It was warm on the wards, and often they would be sitting on their beds in just their Union Jack boxer shorts. Above their shorts, they looked as fit and healthy as butchers’ dogs: below their shorts, there would frequently be nothing. One lad in a wheelchair was so young that he was annoying his fellow patients by helping himself to their sweets.

Broken bodies, shattered minds, lost lives: these tragedies were being repeated across Afghanistan and Iraq, and in countless homes and hospitals of the United States and its allies.

Estimates of the number of people killed in Iraq between 2001 and 2014 vary wildly from around 150,000 to well in excess of 450,000. Nobody really knows how many were injured. Thousands more were killed and maimed following the emergence of the Islamic State (IS) group.

According to the Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs at Brown University, more than 175,000 people had lost their lives in Afghanistan, even before the Taliban began its rapid advance across the country earlier this year. More than 50,000 of these were civilians. A further 66,000 people are estimated to have been killed across the border in Pakistan.

Earlier this year, US President Joe Biden gave the kaleidoscope a good shake, ordering the withdrawal of all US forces from Afghanistan by 31 August. Nobody yet knows where the pieces may fall.

By July it was clear that the US was serious about leaving before the 20th anniversary of 9/11. At the beginning of the month, American troops slipped away from their sprawling base at Bagram in the dead of night. They did not tell allied Afghan troops that they were leaving, and literally switched the lights off as they departed.

Most British forces withdrew from Iraq in 2011; from Afghanistan three years later. Two days after US forces left Bagram, the British government also announced that its few remaining troops were being withdrawn from the country. In fact, their flag-lowering ceremonies had already taken place, largely in secret.

The rapid evacuation of 2,500 US combat troops from the country - and, more significantly, the withdrawal of American air cover - triggered a precipitous collapse in the morale of the Afghan government and the fighting spirit of many of its troops.

Among the first to fall were the provinces in the north, including the border posts controlling access to the new bridge that spans the Panj to Tajikistan. Then one city after another capitulated, sometimes after pitched battles, sometimes following the time-honoured Afghan traditions of negotiations between opposing forces.

Finally, the Taliban swept into Kabul, American power retreated behind the perimeter of the city’s airport, and thousands clamoured outside, begging to be rescued. Afghanistan had turned its sorry circle.

Amid the woeful and grotesque scenes of those final days - young men falling from aircraft, desperate human beings dying in an open sewer while cats and dogs were ushered to safety - it is easy to forget how much support there had initially been for the war in Afghanistan, if not for that in Iraq.

In the immediate aftermath of 9/11, many people around the world thought it was inevitable that the US should move to quickly topple the Taliban regime that had given al-Qaeda the time and space to plot the attacks.

Hindsight - “the super-power of historians” as one recent historian of the war in Afghanistan puts it - suggests that the US and UK should perhaps have left the country promptly, in 2002 or early 2003, while they were ahead.

Instead they stayed, and fought a war that was almost certainly unwinnable.

Iraq, on the other hand, was always going to be a disaster, given that the prospectus for the war had been utterly false, and the official arguments in its favour so dishonest.

In Washington and London, political leaders “believed” Saddam Hussein possessed weapons of mass destruction because they wanted to believe it, not because there was any intelligence to support this possibility.

The claimed links between Saddam and al-Qaeda were a lie, based in part upon the torture of Libi, the man who had been sealed in a coffin at Bagram.

Given the depths of the carnage, the deaths, the amputations, the epidemics of poor mental health - and let us not forget, the costs in treasure as well as blood - there has been remarkably little public reflection by those responsible. No mea culpa has been heard from the White House or Downing Street.

Sir John Chilcot’s report, when it was published in 2016, more than 13 years after the invasion, was highly critical of the British government. It was big news in the UK for all of 24 hours. Then the UK media switched back to Brexit.

Meanwhile, Islamic State Khorasan Province is mounting suicide bombings and rocket attacks in Kabul, inmates are still incarcerated without trial at Guantanamo, and Islamist militancy remains a fact of life from west Africa to southeast Asia.

Biden insists that the days of US troops travelling far and wide and attempting to do good by military force are finally over. Yet the president is also promising to avenge suicide bombings, and Afghan children continue to be killed by American bombs that fall on their families’ homes.

It seems likely that the forever wars may not be coming to a close just yet.

- Ian Cobain’s Cruel Britannia: A Secret History of Torture, is published by Portobello Books

Photo: The Iraq Olympic headquarters in Baghdad burns behind a statue of Saddam Hussein during the US invasion of Iraq in April 2003 (Peter Nicholls/The Times)

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].