9/11 attacks: Twenty years later, fear still lingers in Brooklyn's Little Pakistan

Like everyone old enough to remember, Zakarya Khan, 47, can recall exactly where he was on 11 September, 2001.

He was at home and one of his roommates had turned on the TV. He remembers asking: "What is going on?" and then recalls seeing the second plane hit the south tower.

The World Trade Center was on fire, and smoke and burning debris could be felt in the air some 11.7km (seven miles) away, in the neighbourhood of Little Pakistan.

Life as he'd known it in his community would change. And twenty years later, things have never been the same.

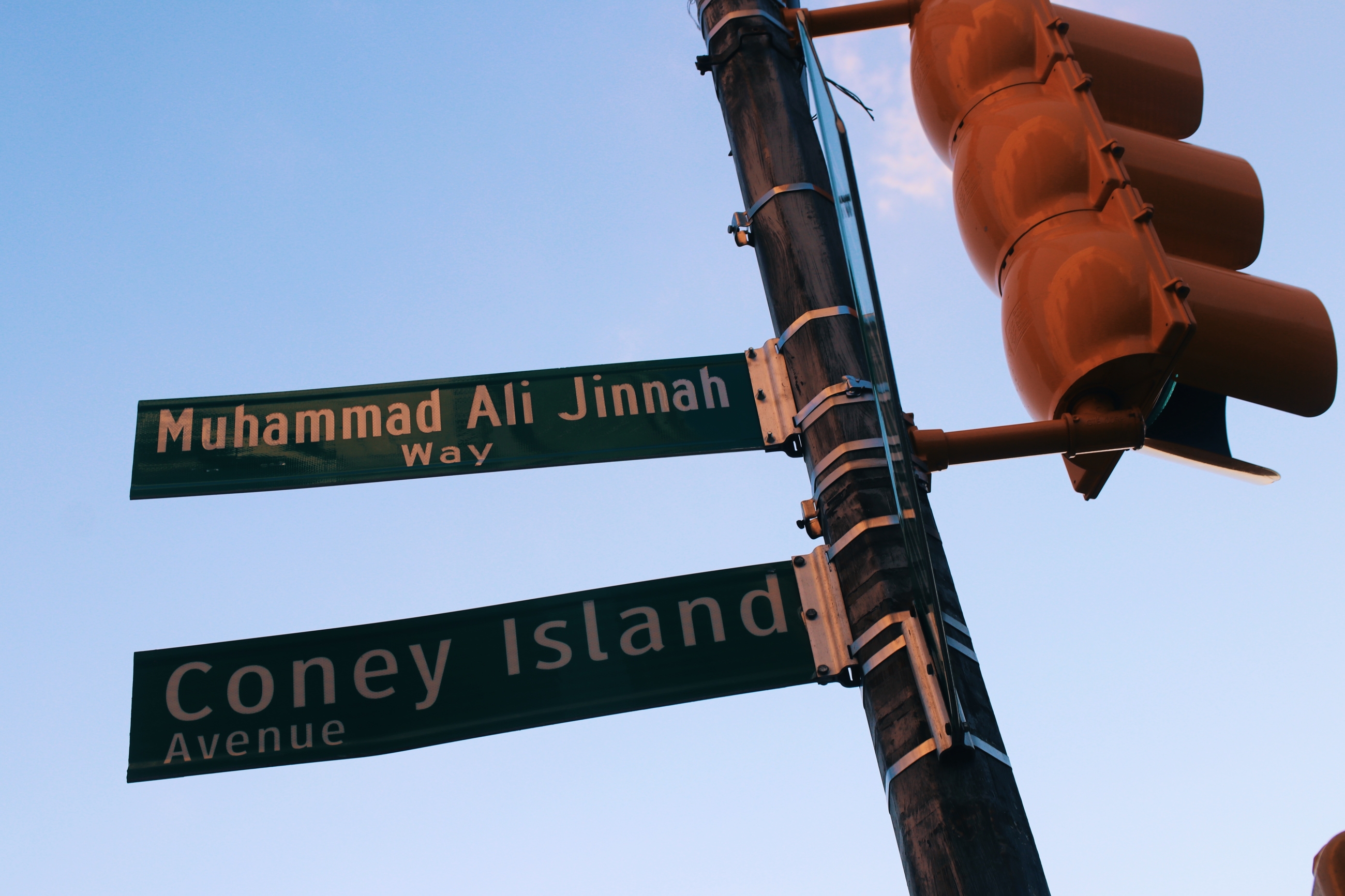

The small strip that is referred to as Little Pakistan - now officially named Muhammad Ali Jinnah Way after the founder of Pakistan - is located on Coney Island Avenue in Brooklyn, New York, and is just 2.4km (1.5 miles) long.

Despite its size, it's packed with immigrants, many of whom migrated from South Asia in the early 1990s; a new generation of children, stories, and sorrow.

Women in shalwar kameez - traditional Pakistani clothing - roam the streets, and men wear thobes and kufis. Every night during the summer, a shop owner hosts a barbeque for his friends and anyone passing by.

There are shops selling gold jewelry and a man can be seen selling sugarcane juice from a truck, squeezing the sugarcane right in front of your eyes - just like in Pakistan. But it wasn’t always like this.

Shortly after 9/11, law enforcement raided the neighbourhood and hundreds of men were detained.

Fear gripped the once vibrant community and, of the 120,000 Pakistanis who lived here, about 20,000 left the neighbourhood - either returning home to Pakistan or moving to Canada, a survey conducted by the Council of People's Organization (COPO) showed.

Storefronts were left empty and businesses shattered.

"Help Wanted" signs were posted on lampposts, and streets at night felt eerie. Panic had taken over.

"We used to go out in shalwar kameez and Islamic dress anytime on Coney Island Avenue. Before 9/11, we thought America was a free country for everyone and there was no fear at all for us," Khan told Middle East Eye.

"Even though people were not documented, there was no fear of arrests, there was no US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE); there was just immigration and they didn't bother anyone. But post-9/11 is when everything changed."

Fight against NSEERS

About a week after the attacks on the World Trade Center, Mohammed Rafiq Butt, a 55-year-old Pakistani New Yorker, was arrested for overstaying his visa. He was detained for a month and eventually taken to a detention centre in New Jersey, where, a month later, he died.

The case prompted Ahsanullah "Bobby" Khan to begin his activism in the United States, just six years after he arrived in America. He is the founder of the Coney Island Avenue Project, an organisation created in the wake of the 9/11 attacks.

Bobby Khan had spent the majority of his life standing against oppressive forces in Pakistan. He was a student organiser and would stand against Pakistan's military regime and religious extremists in the 1970s. He has been tortured, and served eight years in a Pakistani prison.

He came to the US to escape persecution, but instead, there was a new fight waiting for him. In 2005, Bobby Khan was named a "person of interest" by the Department of Homeland Security, a status that would last until 2013 and take a definite toll on his mental health.

"I was called a 'person of interest'. A person of interest is someone like Osama bin Laden. It is not me. The Department of Homeland Security started collecting information from back home, since there was nothing they could find that I was doing wrong here," he said.

"I was an organiser against the military regime in Pakistan. So what? That is my pride. I was scared for my kids and my family. I came all the way from Pakistan here to live a peaceful life and enjoy democracy and freedom of speech and expression, and that dream was smashed after 9/11."

Bobby Khan would spend the next twenty years fighting the racist policies of the US government. With the Coney Island Avenue Project, he would go on to help thousands of people from being deported, raising funds for the families of those who were detained.

They would fight against policies such as the National Security Entry-Exit Registration System (NSEERS), a programme created a year after 9/11 which targeted foreign nationals from 25 Muslim-majority countries, including Pakistan.

It would require foreign nationals to register with the government each time they left or entered the country, and resulted in more than 80,000 men undergoing registration with thousands subjected to interrogation during the decade-long programme, which was finally disbanded during the administration of President Barack Obama.

According to Ahmed Mohamed, CAIR-NY legal director, NSEERS was a shameful moment in American history.

"After 9/11, this country really abandoned its basic principles of due process and equal justice under the law when it came to Muslims or individuals who were perceived to be Muslim, out of fear, out of Islamophobia," he told MEE.

"This impacted American Muslims in every way, especially in their daily lives, their ability to feel safe within their communities here in the US, their ability to practice their faith without being subjected to unwarranted surveillance or unfair and unequal treatment, and the NSEERS program was just one example of it.

"The evolution of multiple programs and things that took place simultaneously - such as the Muslim ban, Muslim surveillance, Joint Terrorism Taskforces - created a stigmatising affect on the Muslim community that 'otherised' us in ways we had never seen prior to 9/11."

'We have the same rights any American has'

Zakarya Khan described the situation in Little Pakistan at that time as pure chaos. He recalled the home raids and the arrest of men in front of their children in the middle of the night.

He recalled how people would be stopped in the middle of the street as the police conducted body searches.

"We are Muslims and we are immigrants. And especially during those days, we didn't have much [power] in the system," he said.

"Right now we have our own Muslim community in different departments; like we have Muslims in law enforcement and political access to leadership. But in those days, we had nothing whatsoever. In those days, people were really scared. It felt like we had been attacked."

Zakarya Khan was a food vendor 20 years ago. His cart was on Broadway in Manhattan, and, for a year, he ran at a loss. He eventually got back on his feet and a few years later, he opened his first bricks-and-mortar business - Gyro King in Little Pakistan.

The small restaurant is now often crowded with people standing outside the shop to give their order. But the majority of his work is not catering, but in community activism.

He helped found the Peace Community Center of NY, known as Masjid Quba, and he founded Peace Children Academy, an Islamic school in the heart of Little Pakistan.

Last year, at the height of the pandemic, he began a non-profit organisation named Brooklyn Emerge, where he runs a youth programme, along with a halal meals project in which they give out hot cooked meals every single day.

"We think that somehow we are aliens. That we are not Americans. And that Americans are some other people who have these agencies and this system in their hands and they can use it anytime against us," Zakarya Khan said.

"But this is our country and this is our land. And we have the same rights any American has. This is why I became an activist after 9/11 and why so many people became activists after 9/11. We thought that if we don't stand up for our community, then who is going to stand up for us?"

Fear quietly lingers on

Anwarul Huque came to the US from India in 1981. His friend lived here and told him to stay for six months, and if he didn't like it he could go back. After six months, Huque was in love.

He lived in Manhattan for two months, where he worked as an accountant for a hotel. He then moved to Brooklyn and would often find himself driving to the Little Pakistan area to buy groceries and halal meat. He soon decided to move there permanently.

In 1998, he opened his own business, an office in Manhattan where he would do taxes and accounting. Life was going well; he was helping members of his community, and his business was growing. Then came September 11.

Though he didn't face any problems from law enforcement, many in his community did. And they would often entrust him with their problems. At one point, he told people to stay with him in his home because they were so afraid.

He ended up having about twenty people in his home and remembers urging them to stay indoors and not stand outside. A lot of them didn’t have legal status in the country and he didn’t want them to be detained or deported.

He was once carrying his briefcase, bringing files to his office with his two children.

"One white guy asked me 'What do you have in this? Is that a bomb?'" he recalled. But despite everything, he never left his neighbourhood.

"I didn't want to leave my culture and my religious values. I have three sons and one son is a Hafidh [a person who has memorised the Quran] because of this community," he said.

Though people now crowd outside Gyro King and walk around the stalls with their families during Pakistan's independence day street festivals, and stand together after jummah outside Makki Masjid conversing with one another, seemingly without a care in the world, the fear that came after 9/11 still quietly lingers twenty years later.

And according to Zakarya Khan, it may never go away.

"Even people who are citizens and have been here a long time are scared," he said. "They worry a time will come when the American government will take everything from us. It's unfounded, but still it's real. In order to remove these fears, I think it will take at least one generation to have that sense of security; to say that 'No, this is our country and we are not afraid'."

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].