'Where to, Marie?': Lebanese comic book tells forgotten stories of country's feminist struggle

"Lebanese feminists are not vectors of westernisation," write the founders of Where to, Marie? Stories of Feminisms in Lebanon, a comic book launched this year. Feminism itself, they argue, is not a foreign ideology "imposed by colonialism", but is instead indigenous to Arab societies. "Women have long been struggling against colonial powers for equality and social justice, as well as against sectarian personal status laws and the entire patriarchal social structure that enforces them."

Focusing on the stories of five fictional female characters, the book traces the history of the Lebanese feminist movement in particular. (All images courtesy Where to Marie?)

The stories, which are written by Bernadette Daou and Yazan al-Saadi and translated by Lina Mounzer, are based on research carried out between 2010 and 2015. Sources range from "semi-guided interviews with feminist actors of different generations" as well as archival photographs, films, books, and articles.

The project came about as researcher Daou, who had just completed an MA thesis on women's rights movements in Lebanon, and writer and comic zealot al-Saadi reflected on how to make Daou's research more accessible to a wider public. “We thought comics would be an amazing educational tool,” al-Saadi told MEE. “In the summer of 2019 we started to discuss the idea of a comic book, and when the uprising erupted in Lebanon, we thought it was the right time.”

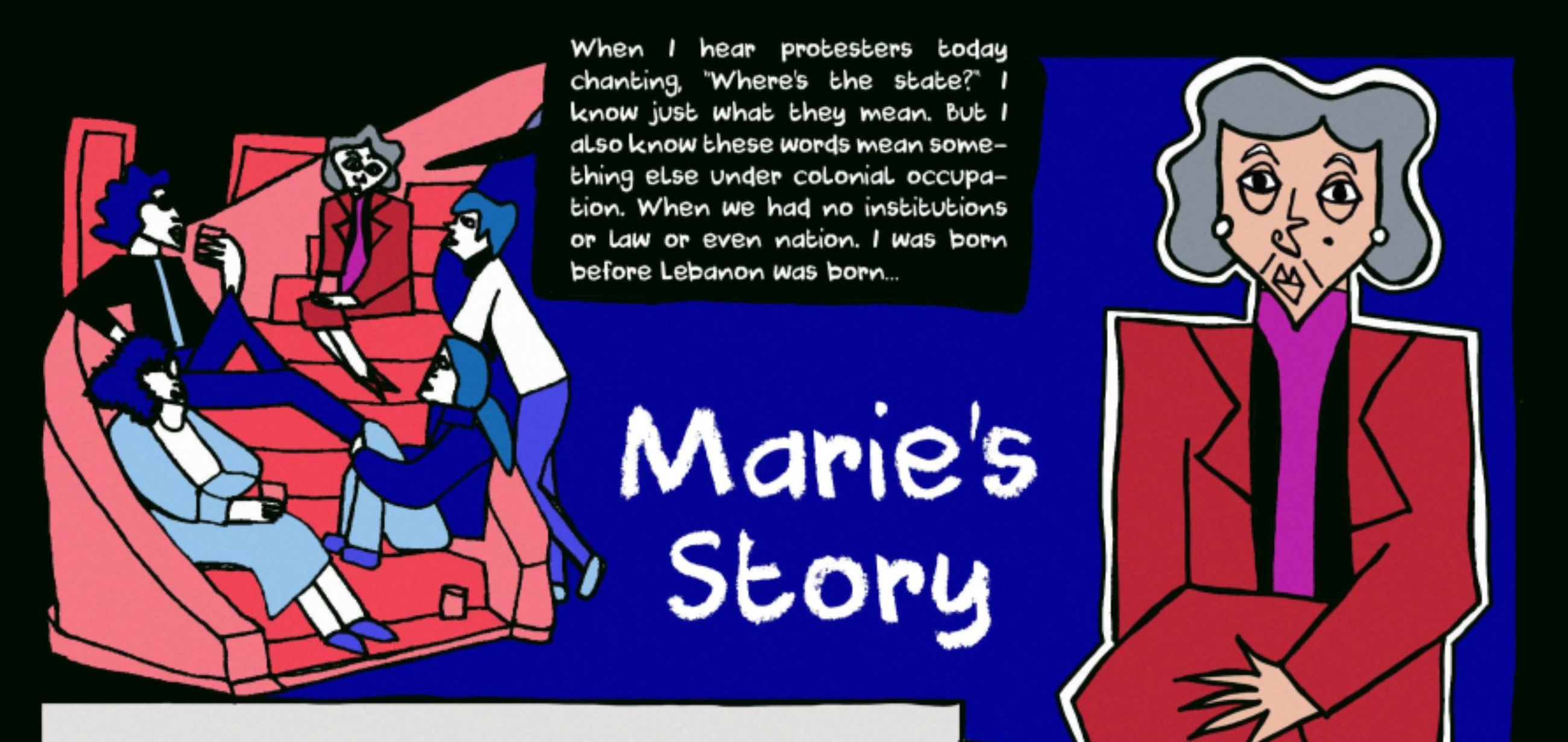

One of the stories, illustrated by Rawand Issa, spotlights a character named Marie, who is "born to a poor large family on the outskirts of Beirut". Growing up under the shadow of the French mandate, she recalls seeing protests and eavesdropping on her factory-working parents' union meetings. Her mother is paid less than her father because she's a woman, but Marie's own life is upturned when her father suffers a workplace accident and loses his job. Marie is forced to leave school and get a job at a factory to help support her family.

Issa says she chose to draw Marie’s story because she felt she could relate: “[Marie would be] the same age as my grandmother, and as a kid I felt very close to her. She used to tell me a lot of stories which I treasure to this day, and inspire me in my work.”

She also wanted to shed light on this particular experience, since she feels that many young women in Beirut feel disconnected to the older generation. “They think they are not real feminist," Issa tells MEE. "I don’t agree and while as younger people we, of course, have different necessities and demands, there's no denying that older women paved the way for us.”

Artist Sirene Moukheiber, who works with a feminist coalition, says that when she first received the draft of the script of Where to, Marie?, she was immediately drawn to the dialogue written for the character named Noora. The young protagonist's story revolves around her struggles with her overbearing parents.

“The way she spoke was so familiar and each phrase felt like something I would say. I fell in love with her!” Moukheiber tells MEE.

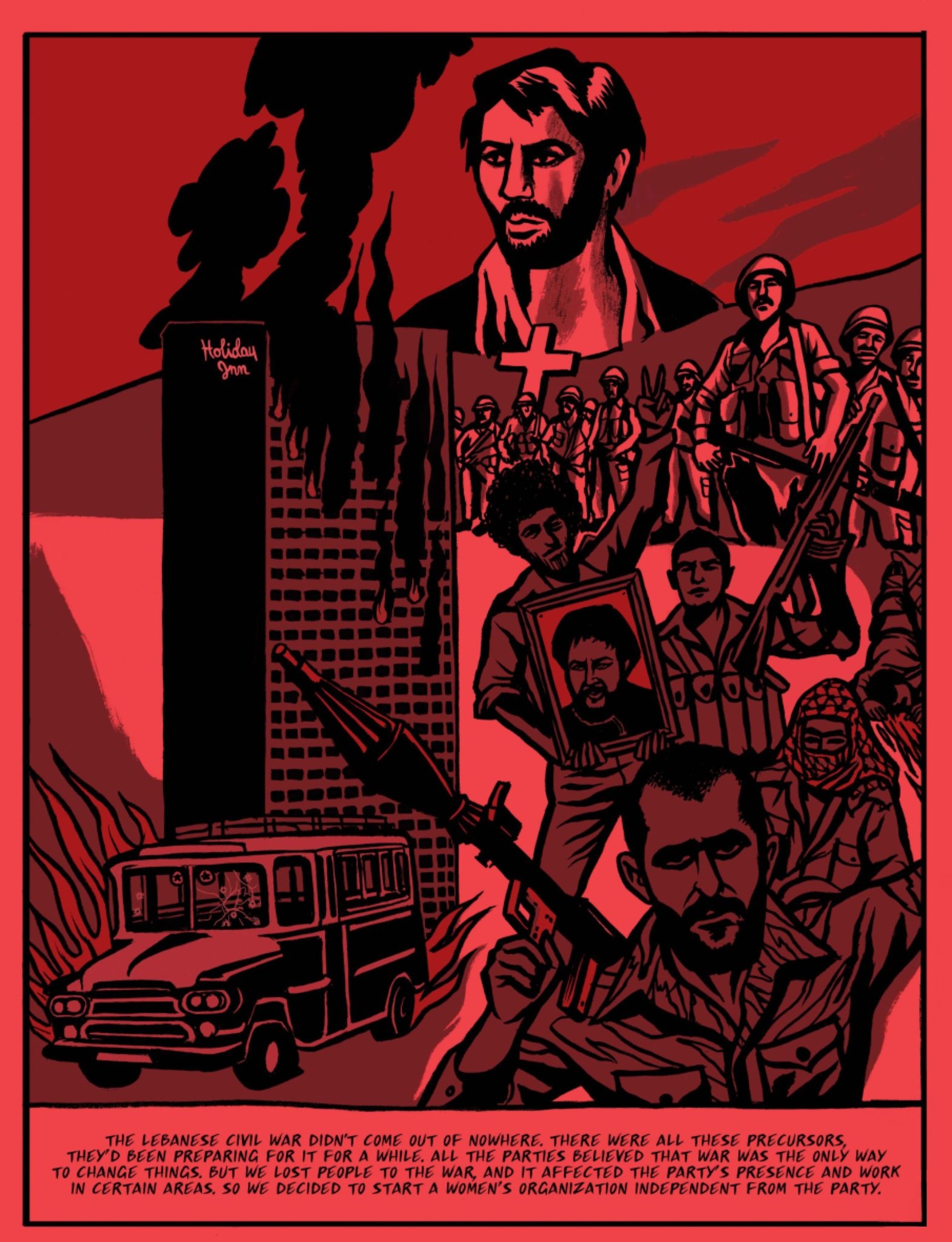

Using a 70s and 80s aesthetic was fun for comic book artist Tracy Chawan, but working on Nidal's story was particularly intense, especially as it involved illustrating a full-page frame to sum up the country's civil war, with all its layers of complexity. “It wasn't easy to decide what to represent from such a complicated war. I discussed it with friends, and decided to keep some of the most visually ‘iconic’ events [like] the Holiday Inn burning from the Hotel wars,” she says.

“It reminded me a lot of what my own mother went through: the horrors and disillusions of the civil war, all her personal and external traumas that came with it [...] I realised that many of those issues still affect our lives: a wave of displacements, a catastrophic economic crisis, horrible violence and just a general loss of hope. I have been going through a lot of it myself while working on Where to, Marie?, digesting all the events of the past few years.”

Artist Razan Wehbi illustrated Lara's story, which sees the protagonist, Lara, trying to enter a political discussion with her male comrades, before being immediately shut down. She says drawing some of these scenes was therapeutic. “I see this happening all the time,” Razan says. “Cis women, trans women and non-binary people are often dismissed with a very misogynist, condescending opposing power.”

When she drew Lara, Wehbi imagined this was her own first protest: “I really felt it was important to represent that anger and frustration she experienced from the get-go.”

The book was completed during a tumultuous period for Lebanon in the summer of 2020, including mass protests, an unprecedented economic collapse, the Beirut blast, and a pandemic. “The challenging environment affected us physically, mentally, financially. It has been a constant battle to keep the momentum going,” says al-Saadi. “The completion of this work is a testament to each person involved, who really believed in this project, and was able to push through the difficulties.”

One of the final pages from the book is a surreal vision of Beirut going up in flames and being flooded at the same time. “It was the hardest page to draw, not just from a technical point of view, but especially on an emotional level,” says Wehbi, who illustrated it.

“I was drawing it right after the Beirut explosion in August [2020], and there was something so hard to represent - my city on fire, in contrast with the water flooding in, devastated by both. That’s how it feels when you are living in Beirut. The opposing feelings of rage and hopelessness, despair and anger, hoping for something to wash away all pain.”

The authors say that they hope the book will help spread awareness of the feminist movements in Lebanon, as well as acknowledging the universality of this hidden history. “We want people to understand that women’s rights are not disconnected from the larger struggle in society, regionally or internationally. They are part of it, inherently linked,” says Yazan, adding that comics are today one of the stronger weapons to produce grassroots narratives.

“I hope these stories will give people extra motivation to continue this struggle across generations,” says al-Saadi “And finally, to build appreciation for our little corner of the globe that is on fire.”

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].