Iraq: Villagers suffer as Arab-Kurdish tensions lead to Islamic State resurgence

One of the most commonly quoted Kurdish phrases is the saying: "Kurds have no friends but the mountains."

But for the inhabitants of the village of Liheban in northern Iraq, just a 68km drive south of the Kurdish capital Erbil, the nearby Makhmour mountains are anything but friendly, having become a base of operations for the remnants of the Islamic State (IS) group.

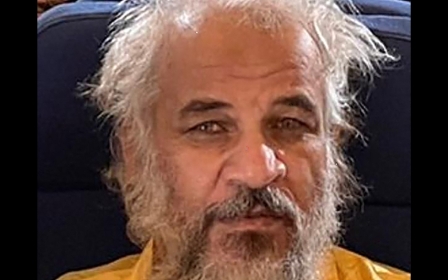

On Wednesday, a gang of IS members raided the home of Mohammed Hassan, as well as the homes of his parents and brother, who also live in the village.

Though Hassan was working in the nearby town of Sargaran at the time, the IS fighters harassed his relatives, telling his children "we know your dad is Peshmerga, we want him".

"IS put their guns on the necks of my parents and children," he told Middle East Eye, speaking at his home.

"They were about to take this one," he said, gesturing to his young daughter, sitting in the small courtyard.

IS confiscated his parents' phones, but they managed to hide a third which they used to contact Hassan's other brother in Erbil.

The lands surrounding Liheban are a vast, flat expanse with only intermittent signs of civilisation. The mountains loom in the distance, thought to house dozens of hideouts for IS militants.

The route from the mountains to the village is clear and there is little to hinder the militants' progress.

The problem, according to locals, is that Liheban, Sargaran and other villages are right in the middle of a 7km area between forces belonging to the federal government in Baghdad and Kurdish forces loyal to the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG).

Between 2014 and 2017, Sargaran and its surroundings were under full KRG control with security responsibility falling to the Kurdish Peshmerga fighters after they drove away IS during their early rampage across Iraq.

In 2017, in the wake of an independence referendum held by the KRG, Iraqi forces launched an operation to recapture the territories under Peshmerga control. Kirkuk, Makhmour, Sinjar and other territories fell back under the control of Baghdad.

This has left a security vacuum in much of these territories.

'We called the Peshmerga to come and help us but they said, "We need an order, we have to contact the Iraqi forces, we cannot come just like that"'

- Mohammed Hassan, Liheban resident

Checkpoints manned by Iraqi forces and Kurdish forces dot the area, but in order to prevent further clashes between the two sides there are large areas with simply no security presence - leaving militants to run rampant.

"We called the Peshmerga to come and help us but they said 'we need an order, we have to contact the Iraqi forces, we cannot come just like that,'" explained Hassan, referring to the day of the attack.

Five families have already left the village in the wake of the IS incursion, and many others in the area are planning on leaving too, fearing no improvement in the situation.

Although Hassan said he had no intention of leaving, he and his family's lives have become unbearable, while his children have been left traumatised.

"We sent them to school today and my son said 'we cannot go, I am afraid they will kidnap me,'" he said.

He and brothers purchased AK-47s and take it in turns to keep watch from the roof of his house. Sleep has become a luxury.

"I've been calling and in contact with the leaders of the Peshmerga forces and the Iraqi forces, and we haven't got an answer that we want yet. We're not sure what's going to happen," he said.

"There's always threats on these villages - there's no forces and nobody can protect us."

'Very localised' attacks

The defeat of IS was declared in Iraq in 2017. The group's self-declared caliphate, with its headquarters in Mosul, was crushed and the remaining fighters fled to Syria or Iraq's many remote regions.

Since then, most of the south of Iraq, including the capital Baghdad, has been spared attacks by the group, which at its height made the threat of car bombings a daily occurrence.

However, in central and northern Iraq - the heartland of the country's Sunni Arab communities - IS has gradually managed to regroup and attacks have become increasingly frequent.

Earlier this week, Iraqi forces announced the capture of Sami Jasim al-Jaburi, IS's financial chief, in what it described as a "complex external operation" outside its borders.

According to a US security official speaking to AFP, the group is now "stretched", leaving it to carry out "very localised" operations against Iraqi security personnel and civilians.

'People nowadays are saying they cannot sleep at night, we have to just look at the cameras constantly, we have to keep ourselves safe'

- Salah, resident of Sargaran

There were 70 IS-related incidents in September, and 103 in August, with 54 people killed and 86 wounded.

Kak Salah, a resident of Sargaran, said the situation in his town and the surrounding area was becoming unbearable.

He told MEE that there had been several people injured and at least one person killed in the past month. Nearby villages had become no-go areas.

"They kidnapped a guy [at one village], and then after negotiations with a tribe they paid money and they gave them back. It's a very dangerous area, those villages," he said.

A few days before Iraq's 10 October elections a number of local Peshmerga fighters return to Sargaran. They have been able to help provide a degree of protection, but believe that there needs to be direct support from Erbil if there's any long-term solution.

"These areas are Kurdish and the Iraqi forces, they don't care about it," said one, Kak Mohammed, brandishing his AK-47.

"These are our lands, they [Arabs] want to come and take it."

Salah, a Kurd, was also adamant that the Peshmerga were needed to maintain order in the area and accused the Iraqi forces of neglecting them.

"People nowadays are saying they cannot sleep at night, we have to just look at the cameras constantly, we have to keep ourselves safe," he said.

"If the situation goes on like this, we will have to [leave]."

Joint patrols planned

The land around Sargaran is dotted with pipelines carrying Iraq's precious fossil fuels and plumes of flame can be seen spouting from a nearby gas plant.

It is these resources that have made control of the area so hotly contested. Though Kirkuk is a often referred to as the "cultural capital" of Kurdistan and claims are made on all sides to historic ownership of land, ultimately the enormous amount of natural wealth in the area is what matters.

The Avana dome oil formation stretches through Sargaran, which along with the nearby Bai Hassan oil field, pumps around 280,000 barrels of crude a day.

Despite the tensions, efforts have been made at cooperation.

There have been intermittent joint operations conducted by the Iraqi army and Peshmerga in an attempt to crackdown on militant activity.

Last month, Iraq's Joint Operations Command announced that they had "started implementing joint activities in the areas devoid of the presence of the federal security units, which are located between the federal forces and the Peshmerga."

The problem for the residents of Sargaran and the other disputed areas is that the lack of a permanent security presence and the levels of bureaucracy required to intervene when IS does attack means they are extremely vulnerable.

Leaving is a luxury that many cannot afford.

Hassan, along with his friends and family, can only rely on themselves for protection now.

He said he believed that bringing back the Peshmerga was the "only way out of this".

"We don't have sleep. Nothing fun," he said.

"We will never leave," he added, explaining. "We don't have anywhere else to go."

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].