Lebanon crisis: How one village keeps the lights on thanks to solar power

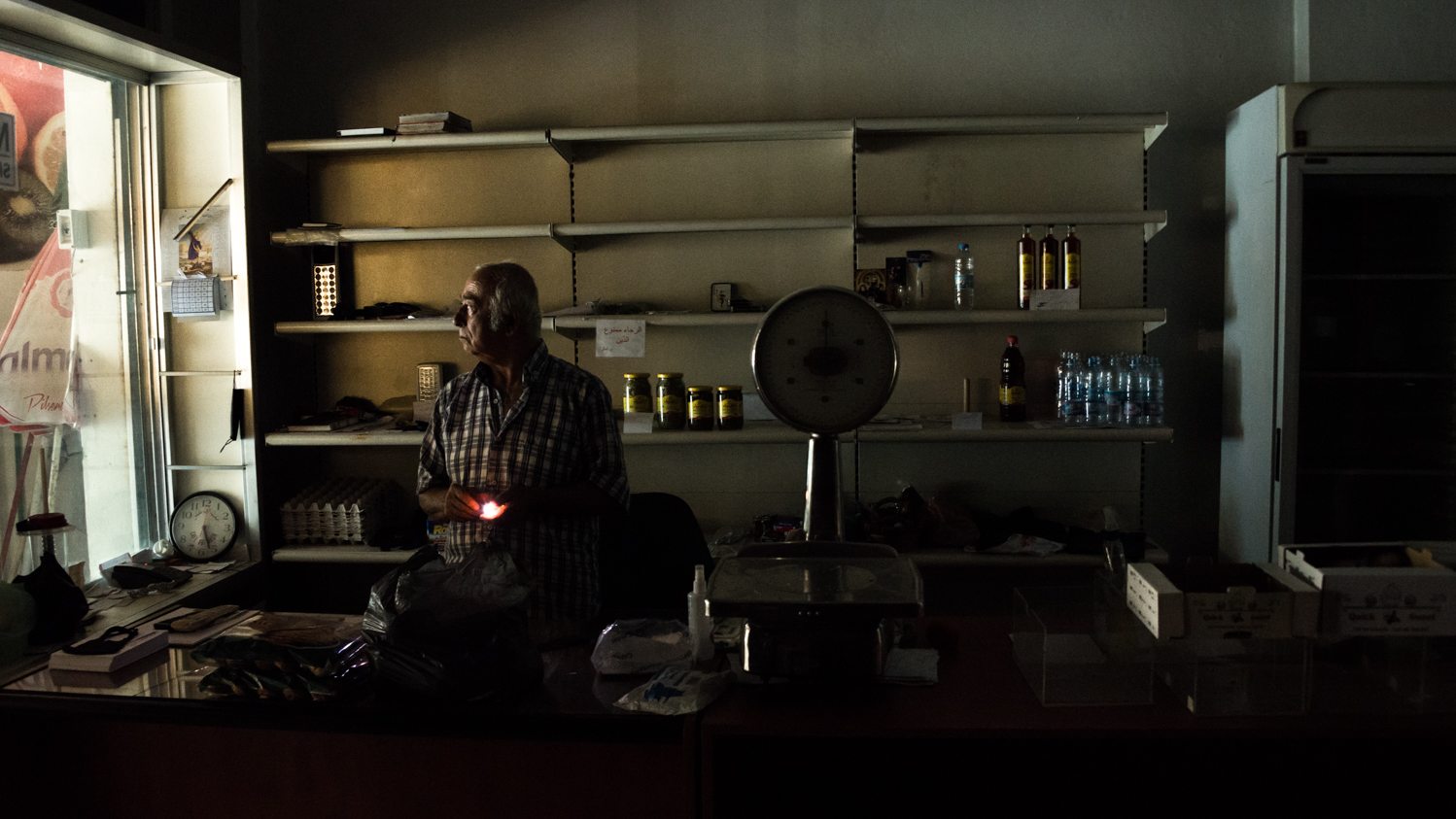

Lebanon gets a scant hour or so of state-supplied electricity per day - most days. Some days, there’s none at all.

The beleaguered country is going through one of the worst economic crises in the world since 1850, according to the World Bank. The Lebanese pound has lost over 90 percent of its value in the span of two years, meaning hard currency required for power station fuel imports is out of reach, causing the near-total collapse of an already insufficient state electricity system.

Those who can still afford it ease the sting of severe electricity shortages with illegal diesel generators. But overstretched diesel supplies can be eked out only so far, and prices have soared over 400 percent as the government has fully lifted subsidies.

For all but the super-rich, 24/7 electricity, or anything remotely close to it, is a distant dream – but not for the village of Bchaaleh

Nestled at 1,200m in altitude in the Mount Lebanon range, Bchaaleh often peeks above the clouds in much the same way its 1,800-strong community has kept its head above the misery of electricity shortages blanketing the rest of Lebanon - all thanks to an experimental solar farm installed in 2017.

Solar voltaic panels hug a south-facing slope on the village outskirts with spectacular views of the Mediterranean sea across olive grove-dotted hills. An array of hundreds of batteries fills several containers nearby, circuit boards bristling with multi-coloured wires, all coaxed into converting, storing and transporting solar energy by operations manager Ismail Aziz al-Bitar.

Riding on a motorcycle he has named Aborami, Bitar takes the steep gravel path to his solar farm-side cabin with ease. He installed the panels here five years ago and has been tending to their every need since.

Bitar navigates a system he knows like the back of his hand to keep the village lights on. A perk of the job is constant power for his own cabin. It’s worth letting him know if you’re organising a wedding or a funeral - he says he’s been known to tweak the schedule to accommodate both.

Bchaaleh demonstrates the potential of alternatives in Lebanon - despite obstacles on the path to more sustainable electricity production in the country.

Endemic electricity issues

State power company Electricite du Liban (EDL) controls access to power nationally. But total capacity falls over 30 percent short of Lebanon’s estimated peak demand, even when the company has enough fuel to operate.

The Lebanese state never quite got around to providing people with 24/7 electricity supply in the aftermath of the 1975-1990 civil war. Even before the economic crisis, the capital Beirut suffered from daily cuts lasting at least three hours, with longer outages in other regions.

During the country’s 2019 uprising, protesters often congregated around EDL headquarters holding banners emblazoned with slogans like “Hello darkness my old friend”. Failure to provide such a basic public service was at that stage an ongoing embarrassment ingrained enough to have become a source of dark banter - but few predicted that the situation would become so dire in under two years.

Solar energy is considered more environmentally friendly than fossil fuel options, but Bchaaleh’s mayor, Rashid Geagea, did not spearhead the project for environmental reasons.

“The problem in the summer, when you’re sitting on the terrace taking your morning coffee is: ‘hrrrmm hrrmm hrrmmm’,” he says, imitating the insidious drone of a generator with a chuckle. “There is no peace.”

From there, the idea was born to try to provide villagers with full-time power without impeding the tranquillity of mountain life.

This 2017 plan to supplement the four hours on, four hours off power supplied by EDL worked very well, Geagea says. But the 12 daily hours once provided by state electricity have dwindled to almost nothing.

“State power comes only one hour of the whole day. The rest is municipality power from solar,” local resident Paula Wehbe tells Middle East Eye. “We get maybe six hours out of 24 with no electricity.”

Villagers pay for solar power with prepaid cards, costing around 400,000 Lebanese pounds - worth around $20 - per 71 kiloWatt hours (kWh). This lasts the Wehbe household up to six weeks if they are careful and switch off anything not in use.

By contrast, residents of Beirut can pay ten times as much each month, for 15 amperes of power from private generator companies. This is enough to run most household appliances - though not simultaneously. The American National Electrical Code, in comparison, requires a minimum 100 amperes electrical service to dwellings with normal appliance usage in the US.

Generator costs are far beyond reach for most when the average salary stands at just $112 per month - and even those who can afford them in the capital still suffer nine to 12 hours of cuts daily.

Hobbled by monopoly

Lebanon’s electricity grid has been supplemented for decades by unregulated private generator firms operating counter to EDL’s official monopoly.

“They use backdoor installation because EDL is not able to supply electricity,” Pierre al-Khoury, president of the board of the Lebanese Centre for Energy Conservation (LCEC), an independent government organisation under supervision of the Ministry of Energy and Water, tells MEE.

But fuel shortages and inflation now make it impossible to bridge the power deficit with illegal diesel generators alone.

Bchaaleh’s solar plant also breaches EDL’s monopoly, Khoury says. Unable to officially support the project because of this, he is nonetheless positive that solar power has the potential to help solve Lebanon’s power shortfall.

'EDL is unable to supply electricity and at the same time Lebanon is prevented from finding an alternative'

- Pierre al-Khoury, LCEC board president

“It's environmentally friendly, it saves money, from an individual point of view everybody should be installing solar,” he says.

Lebanon is rich in renewable energy resources, with an average of 300 days of sunshine a year, but developments within the sector outside of EDL are illegal without hard-to-come-by concessions.

“It’s a sad situation because EDL as an institution is unable to supply electricity and at the same time Lebanon is prevented from finding an alternative,” Khoury says.

Khoury describes current conditions for people in Lebanon as “torture”, but is confident that change is coming.

“Now we’re witnessing a crazy increase in demand for solar,” he says. Solar installations so far this year already number as many as in the entire preceding decade, he claims.

Lebanon came in just under a government target to install 100 MW of solar power capacity by 2020, and has a new target of 1,000 MW by 2030. Khoury estimates total solar capacity will be around 194 MW by the end of 2021.

Meanwhile, LCEC has been working with the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development on a new draft law submitted to the Ministry for Energy and Water on 14 October, which would allow private organisations to generate and run green energy through EDL’s network.

If passed, Khoury says, the legislation to decentralise renewable energy production could be a game-changer for Lebanon.

“At some point in time, there will be a meeting point between the approach we’re using with the new draft law and de facto solar projects in villages,” he says.

Going the extra mile

Bchaaleh’s solar initiative has faced some obstacles. The municipality and E24, the tech company they partnered with to orchestrate the solar project, recently went their separate ways.

The company wanted to turn a profit or at least break even, which would have required a buy-in from 600 homes, according to Geagea - but Bchaaleh only has 250.

'In a community where people have a good relationship with their mountain, with their roots, they are compelled to come together to make a better future'

- Rashid Geagea, mayor of Bchaaleh

Geagea says he just wants reliable power for the village and intends to run the solar farm as a not-for-profit.

E24 did not respond to an MEE request for comment.

Operational costs of Bchaaleh’s solar farm may now rely in part on villagers working as a collective to contribute to the capital required to take ownership of their own electricity. Public consultation meetings and tangible results have built trust that the municipality is working in the residents’ best interests over Geagea’s five-year term.

“I don’t want thanks just for doing my job,” Geagea says. “I should be achieving things for the community, it shouldn’t be unusual.”

The mayor says he wants out with “wasta” - nepotism, or connections that curry favour - and in with new blood and proactive community building.

“We love our village, this is where we were raised, shared memories, where we have our roots,” he adds, likening the roots of his community to those of the olive trees growing in Bchaaleh, thought to be among the oldest on the planet.

Wehbe says if she is asked to invest money, she will. “We can feel the care for the village directly, the municipality doesn’t only talk the talk, they are going the extra mile,” she says.

Like many in Bchaaleh, the Wehbes have chosen to stay in the village instead of their other home in a generator-reliant suburb close to Beirut. “There’s no work in Zouk (Mikael),” Wehbe says. “There’s nothing, everything stopped, there’s no electricity, so there’s no more activity.”

Wehbe says solar electricity has brought life to Bchaaleh: “Everyone is here because it’s way easier… life is actually still functioning here more so than on the outside because of what the municipality is offering.”

Houses that used to serve as secondary homes for villagers working in the capital have become primary residences once again.

Wehbe feels lucky to have a better option than most people trying to weather Lebanon’s crippling series of crises.

“But this web of corruption in the core of our country has caught us all, and we don’t have choices anymore,” she adds. “I would love to be able to work according to my own choices, to feel productive, make money, and be free to live outside of Bchaaleh.”

Geagea remains hopeful that Bchaaleh can thrive despite the country’s struggles.

“In a community where people have a good relationship with their mountain, with their roots, they are compelled to come together to make a better future,” he says.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].