Sudan coup 2021: What's at stake for neighbouring powers

Sudan’s neighbours, who have a lot riding on the rise or fall of the country’s faltering democracy, are calculating.

While some have explicitly called for a return to civilian government since Monday’s coup, others, who would prefer military rule, have kept a low profile.

Much remains unclear. But given the timing and apparrent unpopularity of the coup, several experts told Middle East Eye they felt the military takeover bears the fingerprints of regional backers.

'We can all assume that regional backing is there, that it exists, but we don't know of any kind of specific guarantees or quid pro quos'

- Cameron Hudson, analyst

“We can all assume that [regional backing] is there, that it exists, but we don't know of any kind of specific guarantees or quid pro quos,” Cameron Hudson, a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council, told MEE.

“There are many countries in the region and beyond who are interested in controlling the narrative and controlling the outcome of events in Sudan for their own interests... they’re all vying for influence here.”

So what, exactly, is at stake for Sudan’s neighbours as the coup unfolds?

The threat of democracy

Egypt, the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia are all deeply invested in Sudan, and have backed the military during the post-2019 transition, hoping to bring Sudan into their sphere of influence.

Burhan himself studied in a Cairo military college, and the Sudanese armed forces regularly conduct military exercises with their Egyptian counterparts (the most recent began last Tuesday.)

Burhan has also made numerous visits in recent years to the UAE, which reportedly sent weapons in April 2019 to Sudan’s Rapid Support Forces (RSF), a paramilitary group linked to the genocide in Darfur.

Meanwhile, Saudi Arabia and the UAE have paid Sudanese troops and paramilitary soldiers handsomely for fighting for them against the Houthis in Yemen.

Egypt, Saudi Arabia and the UAE all reportedly encouraged Burhan in 2019 to oust longtime autocrat Omar al-Bashir - who, despite growing closer to the two Gulf states, had also struck deals with Turkey and Qatar towards the end of his reign, convincing the Saudis and Emiratis that he was “unreliable and needed to be replaced”, according to Sudan scholar Jean-Baptiste Gallopin.

The three countries have called for calm in Sudan since the coup began. Notably, none of their statements advocated a return to civilian rule.

On Tuesday, the US State Department said Saudi Arabia’s foreign minister condemned the coup in a call with Secretary of State Antony Blinken, part of White House efforts to rally Gulf leaders “to make sure that we’re closely coordinating” to send “a clear message to the military in Sudan”.

But none of the countries appeared on a Friends of Sudan statement condemning Burhan's takeover the following day.

“There’s no love lost for civilian rule in Sudan from among many of Sudan’s closest allies, or rather, the military’s closest allies,” said Hudson.

This, analysts say, is because of the explosive potential fallout of a successful transition to democracy on their doorstep.

“I think it's fair to assume that Cairo and some Gulf countries would really worry about how inspiring it would be to see the Sudanese people turf out their military, autocratic leader, and then replace him with a working civilian government,” Jonas Horner, senior Sudan analyst at Crisis Group, told MEE.

‘Somebody else’s coup’

As Burhan announced his power grab on Monday, he did so in front of two flags: one Sudanese, one Egyptian.

Somewhat strangely for someone trying to hand himself unchallenged power over his home country, he seemed to be doing so from abroad - in Cairo.

“Cairo appears to have been integral to Monday’s coup,” Horner told MEE. There are “all sorts of things wrong” with declaring a coup from abroad, “in terms of looking weak, unsure of your position, and maybe looking like this is somebody else’s coup as well”, he added.

“It’s clear that General Burhan must have gotten assurances, political and economic, from regional powers in Cairo and Abu Dhabi during his trips there,” Kholood Khair, managing partner at Insight Strategy Partners, a think tank in Khartoum, told MEE.

But it’s not just the loss of a military ally and the demonstrative effect of a flourishing democracy that Egypt fears.

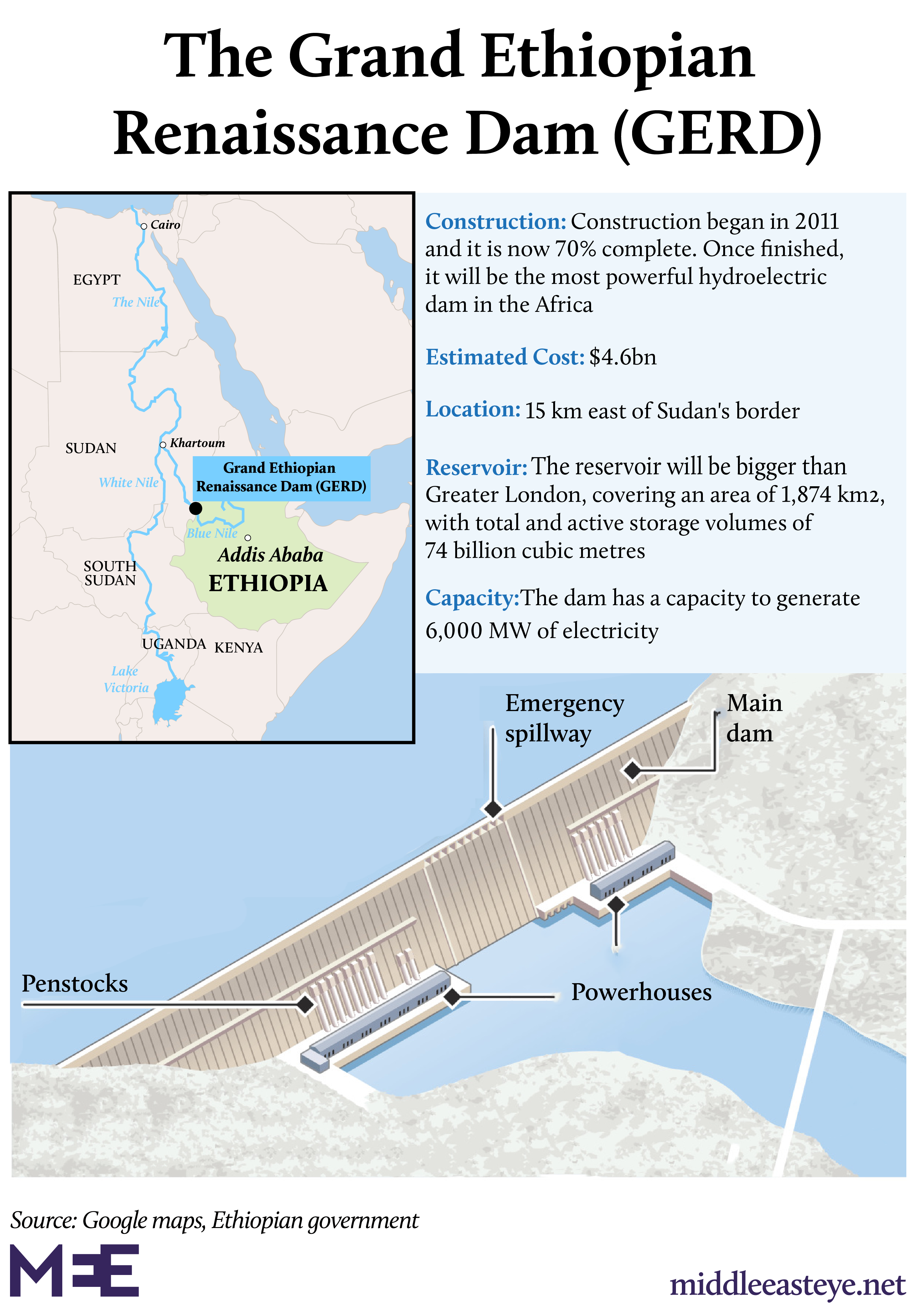

Great Ethiopian Renaissance Dam

For the past 10 years, a mega dam has frayed relations between Egypt, Sudan and Ethiopia.

The latter’s construction of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) on the Blue Nile has alarmed the two downstream countries.

Cairo fears the dam will imperil its supplies of Nile water, while Khartoum is concerned about its safety and water flows through its own dams and water stations.

“From a regional perspective, GERD is an existential question for Cairo,” Horner said. “There's a sense that a military - or military friendly - government in Sudan would be more likely to take care of Egyptian strategic interests around the Nile.”

Joint Egyptian-Sudanese war games earlier this year, in Sudan’s south, were called “Guardians of the Nile”, in what was seen as a clear message to Addis Ababa.

After Monday’s coup, Ethiopia, whose tense relationship with Sudan has been further exacerbated by the Tigray conflict and weapons smuggling in recent months, called “on all parties for calm and de-escalation in the Sudan and to exert every effort towards a peaceful end to this crisis”.

"Ethiopia reiterates the need for the respect of the sovereign aspirations of the people of the Sudan and the non-interference of external actors in the internal affairs of the Sudan," a statement added.

The Gulf

Gulf countries have other considerations, too.

“The vast majority of livestock that's eaten in the Gulf is raised in Sudan,” said Hudson. The same goes for wheat, sorghum and sesame, he added.

“Sudan is the Gulf’s bread basket. Ironically, the Sudanese are food insecure because they send all of their food and livestock to the Gulf and the money comes back not to the people, but to the military.”

Then there’s the Red Sea. Not only is it resource rich, but roughly 12 percent of the world’s shipping passes through it, travelling to and from the Suez Canal.

That means Sudan’s 400 miles of coastline, home to the cities of Port Sudan and Suakin, which in 2018 was leased to Turkey for 99 years and has been a site of regional jostling, is of key strategic importance, especially given the instability in neighbouring countries.

Normalisation with Israel

The coup will also have repercussions for Israel.

In October 2020, Sudan agreed to a US-brokered deal to normalise ties with Israel, following similar moves made by the UAE and Bahrain. Morocco followed suit in December. The agreement still needs to be approved by Sudan's parliament.

On Monday, Washington said that it would have to reassess Sudan-Israel normalisation in light of the coup.

"The many partners now we've spoken with have expressed a similar degree of alarm, concern and condemnation of what we've seen take place in Khartoum in recent hours," US State Department spokesperson Ned Price said during a news conference.

One Israeli official said the country should support Sudan's General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan following Monday's coup in the country, as he was "more inclined to bolster ties with the US and Israel" than the deposed prime minister Abdalla Hamdok.

The official told Israel Hayom, a popular right-wing daily, that "in light of the fact that the military is the stronger force in the country, and since Burhan is its commander in chief, the events of Monday night increase the likelihood of stability in Sudan, which has critical importance in the region".

The current situation, however, may be too fragile to forge ahead with more concrete cooperation.

Turkey and Qatar

In the years since Bashir - an Islamist - fell, Sudan’s ties with Turkey and Qatar, who are sympathetic to the Muslim Brotherhood, have weakened, as Saudi and Emirati support has increased.

Turkey called on all parties in Sudan to “refrain from disrupting the transition process”, while Qatar said that it wanted to see the “political process get back on track”.

For now, the longevity and consequences of Monday’s coup are far from clear.

“In many ways, this is a miscalculation that the military has made,” Horner said. “I think they underestimated the resilience and determination that the street would show in the face of this.”

“The military's strategic approach appears to have largely been based on creating conditions where people felt that the government was not responding to their needs,” he added.

This, Horner argued, not only shows a lack of understanding of what people in the streets wanted, but also “reflects how existential this transition to a democratic participatory government is for the military”.

“The military's been in power in Sudan for 52 of the 65 years since independence. And so they're very reticent about giving up power,” he said.

“The country's about to get crippled by mass civil disobedience. So they need external support. Otherwise this is not going to work. I think that's the bet that's being made.”

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].