Jordan: Journalists calling out corruption muzzled by cybercrime laws

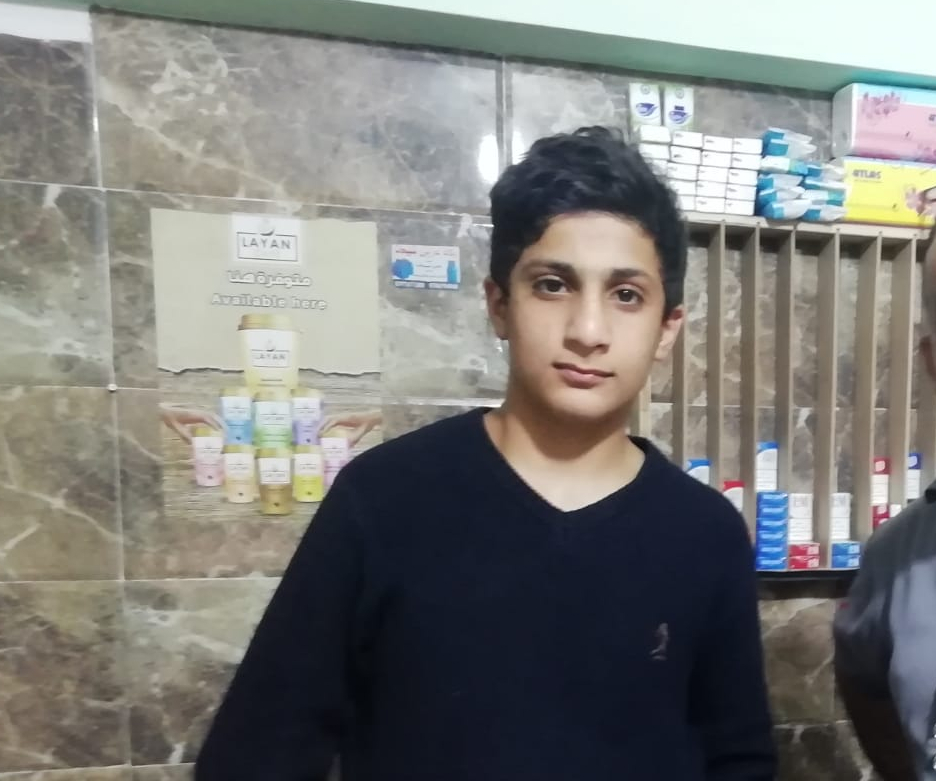

A coffee stand in Ramtha District, 80km north of Amman, has suddenly become a mecca for activists and people wishing to show solidarity with its detained owner and his son, who is now running it.

Kameel al-Zoubi was arrested on 24 October for posting on his Facebook page that the wife of Jordan's prime minister, Bisher Khasawneh, receives a salary of JD5,000 ($7,000) from an official agency.

Khaswaneh had issued a complaint based on the country's cybercrime law, stating to a court that Zoubi's post was "hurtful to him morally and psychologically" and that "it also contained fake news".

On Sunday, political activists staged a sit-in in front of Marka prison to demand Zoubi's release.

Zoubi is just one of hundreds of political activists, journalists and regular citizens who have found themselves in jail, or in front of a judge, for what they have posted on social media reflecting their political views.

The National Centre for Human Rights, a semi-governmental agency, stated in its annual report for 2020 that “the detention of individuals for what they express is continuing”.

The report, which was issued last week, said that “some of the detentions were carried out because of the right of expression on issues that have a direct bearing on the coronavirus".

The continued detentions are based on Article 11 of the Cybercrime Law, under which an unprecedented 2,140 cases were brought in 2020, compared to 982 in 2019.

Article 11 of the 2015 law states that “anyone who on purpose posts or reposts statements or information on the internet, that include tort and slander, or the denigration of anyone, faces no less than three months in jail and a fine of no less than JD100 ($140) and not more than JD1,000 ($1,400).

Gagging those who want to speak out

Ahmad Hassan al-Zoubi, a satirical writer and distant relative of Kameel, told MEE: “There is abuse in the way the Cybercrime Law is applied to gag those who want to speak out.

"Before the law, I used to write a lot of criticism of corruption without any problem. Today I have to think: will this lead to my conviction if the case is brought in front of a judge?" says Ahmad, who has 19 cases against him, among them 14 based on the Cybercrime Law.

"Most cases against me are raised by government agencies. In those raised by non-government agencies I was vindicated.”

Zoubi says that Kameel has a right to raise the issue he did. "In Jordan, we have many stories in which sons, wives and other relatives of officials have become rich by using the offices of their relatives," he said.

"Maybe what Kameel wrote was not backed by documents but was it necessary to use such hard abusive use of power prior to the investigation?

"The barging into their shop by security forces was all done because this person is a political opponent of the prime minister.”

Defence order

Jordanian laws are full of vague statements on crimes such as "attempting to destroy the regime" or "causing friction between the components of the Jordanian people," along with lese majeste, meaning an offence against the dignity of the king.

The flexibility in their interpretation has also contributed to the imprisonment of political activists, teachers and independent unionist activists, who have been sent to state security courts simply for stating their positions on social media, or carrying out a peaceful demonstration.

Meanwhile, restrictions on freedom of expression have only increased since the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Defence order No. 8, which was issued in April last year under Jordan’s state of emergency, prohibits "publishing, re-publishing, or circulating any news about the epidemic in order to terrify people or cause panic among them via media, telephone, or social media”.

The order specifies penalties of up to three years in prison, a fine of JD3,000 ($4,200), or both.

Nidal Mansour, the founder of the Centre for the Defence and Protection of Journalists (CDPJ), told MEE: “Defence order number eight has increased punishments, including against whoever is accused of starting a rumour.

"This has created unprecedented pressure on the media and forced many to think long and hard before publishing anything, especially if such information contradicts the official line in terms of the virus, the number of cases, and so on.”

The CDPJ has issued a report entitled “Restricted Media” in which Mansour wrote: “After years of direct intervention, the media has reorganised itself and the editorial teams (chief editors, managing editors, reporters and the newsdesk) are now doing all the heavy lifting work pre-publication, going through what will be published, in order to remove anything that they consider to be in contradiction to the government line and direction.”

'Online patrols'

There are around 9.4 million internet users in Jordan, including 6.3 million with Facebook accounts.

In July, the government announced it was beginning "online patrols" to keep an eye on what was being published on social media.

The patrols are made up of security personnel who monitor what is being written on social media, and then follow up with the authors if they feel a crime has been committed.

Facebook is used by many political opponents in Jordan, who find its live video stream a perfect tool for criticising the government and sometimes the king.

The continuing deterioration of the economy has resulted in a spike in the use of live streams.

In recent months, the government has moved to cancel such coverage, including streams of protests by the teachers' union, and demonstrations over the case of Prince Hamzeh and the Pandora documents.

Jordan has also blocked the Clubhouse application.

Government review

King Abdullah II last month asked the government to study all convictions brought under the lese majeste code in order to provide a private pardon to many of those who had been convicted under the law.

Last week, the government also promised it would “review the Cybercrime Law” in a statement made by the new minister of media affairs and the government spokesman, Faisal Shboul.

Shboul told journalists on Thursday that “there is an initial government plan to review all the legislation that is regulating the work of the media in cooperation with the Jordan Press Association". "This includes the cybercrime law,” he added.

Khalid Khlaifat, a lawyer specialising in cases involving printing and publication, including cybercrimes, told MEE: “There is a need for a full review of the Cybercrime Law."

Khlaifat has called for the replacement of the existing law with another law rather than amending it.

He says that there were many issues that need to be addressed in any new law and many others need a totally new text.

“A review between what exists now in the Cybercrime Law and the telecommunications law is needed so that internet users and the media know what the limitations are of what they can do legally online,” he said.

'War against journalists'

Nidal Salameh is a journalist who is still waiting for the result of a case brought against him by the government and some of its ministers.

In a tweet he posted in 2020, Salameh called on the minister of interior to stop the heavy-handed treatment of teachers, whose protests had been violently broken up.

Salameh told MEE: “Using the law to suppress freedoms has become a sword against the necks of journalists who want to publish documented criticism.

'Using the law to suppress freedoms has become a sword against the necks of journalists who want to publish documented criticism'

- Nidal Salameh, journalist

"This is a war against journalists and activists, and it is necessary that all journalists unite and call for the abolishment of this law which is hampering efforts to expose corruption.

"I was in jail for one month and five days on a case that was well documented and I was released thanks to a general amnesty.

"This restriction is contrary to what the king had called for when he requested a joint effort to fight corruption.”

Jordanian parties have called for a demonstration against the government on 12 November after Friday prayers in front of the Husseini Mosque in Amman.

Among their demands are the suspension of the Defence Law, including order No 8.

Meanwhile, Kameel remains in jail and his son Bassam keeps customers happy by providing them with hot coffee at the expense of his education.

Supporters know they can do little to help, but at least they buy the coffee as a token of support for his imprisoned father.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].