Let it be Morning: Israeli director rejects categorisation for award-winning drama

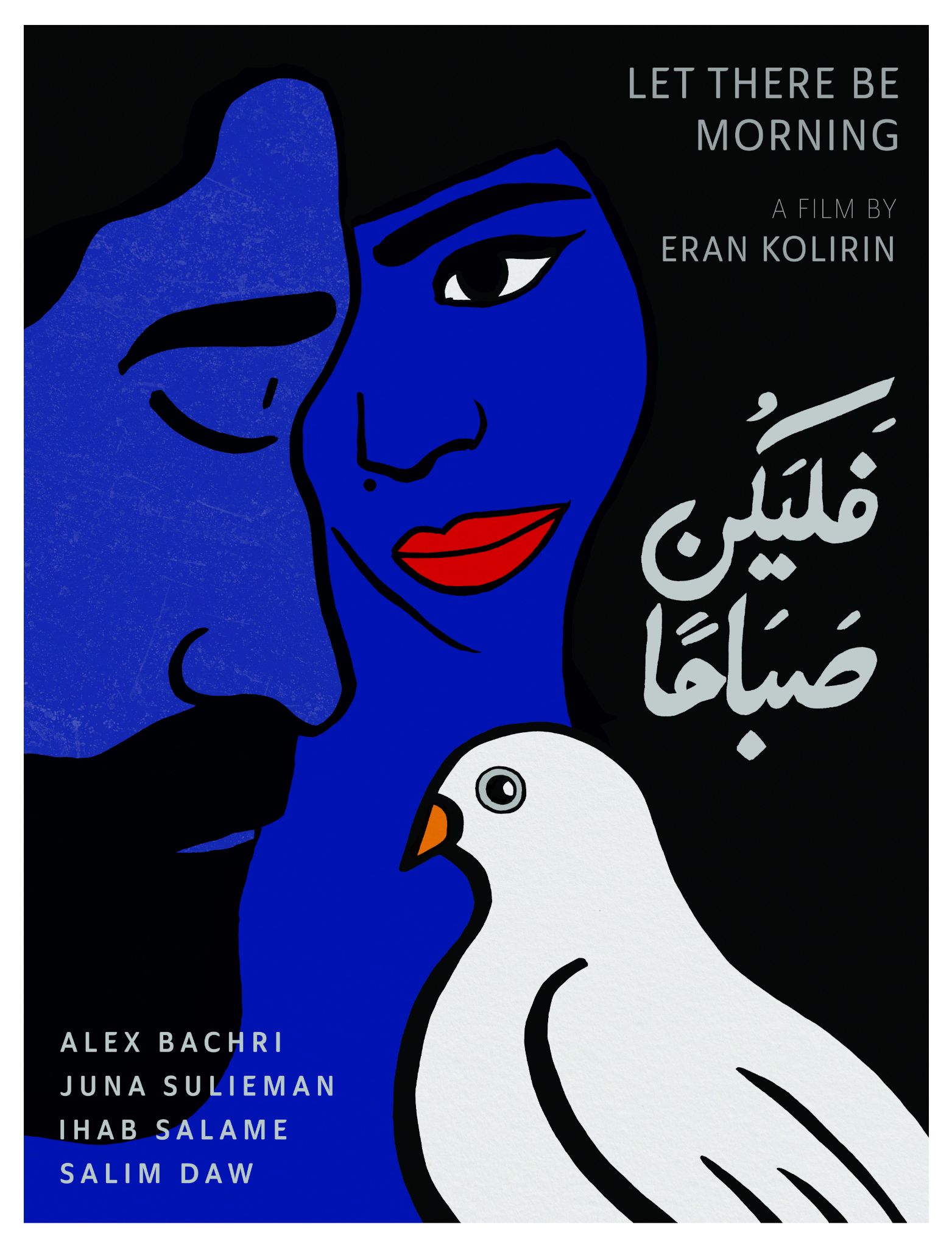

Let It Be Morning opens with a wedding. The groom’s older brother, Sami (Alex Bakri) is an urbane Palestinian IT executive residing in Jerusalem with a young son and straight-shooting wife Mina (a striking Juna Suleiman).

From the very beginning, it is clear that Sami is a fish out of the water. Sami hasn’t been in touch with his family and old friends for years. There’s a great gulf in the way he converses, moves, and generally holds himself, and the rest of his bumbling relatives and past acquaintances.

Distanced and restless, Sami is already craving to return promptly to the city, partially because he’s having an affair with what appears to be an Israeli woman.

For some inexplicable reason, the village suddenly falls under a military siege. Both the village denizens and Sami find themselves cut off from the outside world as communication is severed and supplies dry up, forcing them, individually and collectively, to search for a way out.

What follows next is an intimate, delicate yet incisive multi-character comedic drama of classism, communal power dynamics, the broken dream of freedom, and the struggle for identity.

The book behind the film

The film, an Israeli production helmed by The Band’s Visit’s director, Eran Kolirin, was adapted from Let There Be Morning, a novel written in Hebrew by controversial Palestinian writer, Sayed Kashua.

Born in the Israeli-occupied Arab district of Tira, Kashua received his education at the Israel Arts and Science Academy in Jerusalem, where he was the sole enrolled Arab. He later embarked on a writing career that saw him become one of the most influential Arab commentators in Israel thanks to his popular column in Haaretz.

His literary career commenced with Dancing Arabs (2002), a semi-autobiographical novel about the experience of a young Arab student in an elite Israeli boarding school struggling to fit in – a theme that informs most of his writing.

Kashua is not the first Palestinian author to write in Hebrew. Atallah Mansour, aged 87, and Anton Shammas, 71 – both first-generation children born after the 1948 Nakba – have preceded him. The 46-year-old Kashua, by comparison, is a third-generation Nakba child who has known no other home than Israel.

In a famous Haaretz column, he justified his decision to write in Hebrew: “I learned that Arabic is a form of a cultural pre-emptive reaction ... which maintains identity and prevents assimilation. I learned that I’m not just writing little stories about life, but that I exemplify a process called ‘distorted Israelisation’ which is bound to fail ... I understood that I would never be welcome, be accepted or become a permanent resident of the Hebrew language.”

The only means by which he could convey the Arab voice to the Israeli public, he deduced early on, is by reaching them in their own language.

Kashua’s writing remains as urgent, as provocative as ever – a rare portal into the systematic ghettoisation of Palestinians by an apartheid state that regards its Arab populace as disposable

Judging by his best-selling novels, TV and film adaptations, and endless press his writings have received, Kashua did succeed in planting the Palestinian narrative within an Israeli political discourse determined to erase the Arab identity from its society.

In 2014, however, Kashua finally decided to leave Jerusalem and move to the US. In a Guardian article published the same year, he explained that:

“Twenty-five years of writing in Hebrew, and nothing has changed. Twenty-five years clutching at the hope, believing it is not possible that people can be so blind.

“When Jewish youth parade through the city shouting ‘Death to the Arabs,’ and attack Arabs only because they are Arabs, I understood that I had lost my little war.”

Seven years later, Kashua’s writing remains as urgent, as provocative, and as unique as ever – a rare portal into the systematic ghettoisation of Palestinians by an apartheid state that, in its most benign intentions, regards its Arab populace as disposable.

‘A suicide mission’

Let It Be Morning is not the first work to be adapted from Kashua’s writings. In 2014, Israeli director Eran Riklis (Lemon Tree, The Syrian Bride) helmed a feature film version of Dancing Arabs whose script was written by Kashua. Two TV series based on Kashua’s work bracketed the film: Arab Labor (2007) and The Writer (2015).

For Let It Be Morning, it was Kashua himself who approached Kolirin to realise the adaptation of his 2006 novel while he was moving to the US seven years ago. Kolirin was familiar with Kashua’s Haaretz column, which he thought was funny, but had not read his novels and never imagined he could adapt his stories for the sheer fact that he’s an Israeli.

“It was a suicide mission, but I was in a suicide mood,” Kolirin told Middle East Eye. “There was a moral side to it though. When someone opens up their house to you and offers you their belongings, it means that they trust you, and trust is the most precious gift someone could grant you. That’s why I was determined to be as open as I can, as honest as I can with the material.”

Kolirin continuously consulted Kashua with the script, sending him multiple drafts over the lengthy writing process, but the latter gave him free reign to adapt the story whichever way he wanted.

The main challenge for Kolirin, who describes himself as a “non-professional director”, was to find himself within a story “which is about a man who’s trying to find himself inside my story” as he puts it.

Adapting Let It Be Morning felt even more gratifying for Kolirin, who is fluent in Arabic, as he ventured to bring the Hebrew-written novel back to Arabic.

“As strange as this may sound, this is a very personal film for me. The family at the centre of the story is not very different from mine,” Kolirin said.

“The estrangement Sami feels towards them is the same estrangement, the same tension, I sometimes feel towards mine. The stakes and story are certainly different, but the story is not the issue for me: it’s the tone, the emotions, the relationships.”

Kafkaesque condition

A key change Kolirin has made from the source novel is altering Sami’s line of work from journalism to IT. In the book, Sami’s role as the sole Arab reporter in an Israeli leftist publication augments his alienation as he becomes conscious of the limitations of freedom given to him.

“The privilege of criticising government policy was an exclusively Jewish prerogative,” he declares in the book. By changing Sami’s profession, a substantial part of this barbed criticism is eliminated, replaced however by a subtler subtext that is no less strident.

This change ends up tilting the story towards the Kafkaesque; this condition, it transpires, is integral to the Palestinian experience

“Like filmmakers, journalists, as characters, were never interesting for me simply because they’re too self-aware. I wanted to have an ordinary hero who thinks he’s away from politics but realises he isn’t after all,” Kolirin said.

“I didn’t want him to grapple with these issues of identity in an explicit way – I wanted him to be non-self-aware. He lives his life, carries out his work, and just doesn’t want to look at the reality around him. But one day he’s finally forced to, and that’s when he starts to question himself, his identity, and his reality.”

This change ends up tilting the story towards the Kafkaesque – an ordinary man who appears to be in control of his life finds himself stuck in an outlandish situation that makes him realise how feeble his existence is. This Kafkaesque condition, it transpires, is integral to the Palestinian experience.

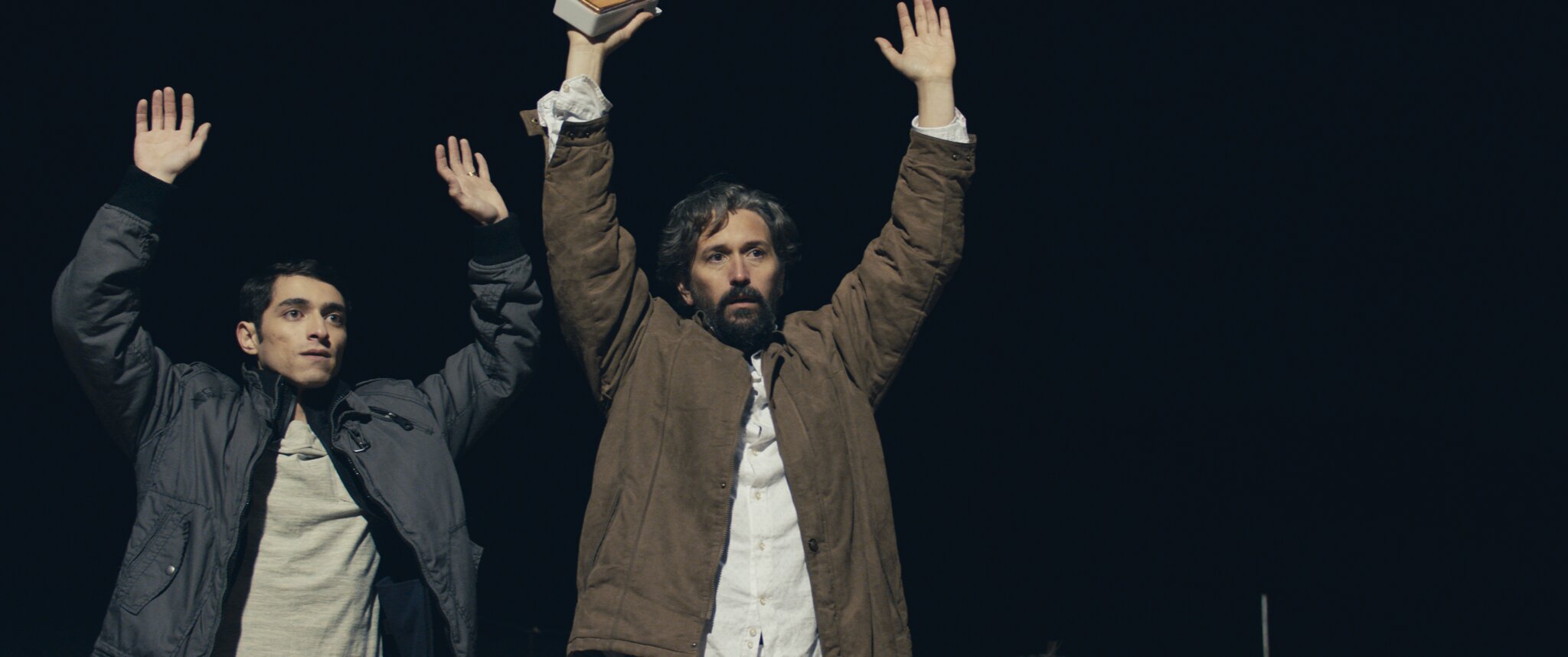

“Sami is treated like a success in his village, and he appears to be on top of things. When he goes and pleads with the young indifferent Israeli soldier at the border to give him any information about what’s happening, his people realise he’s powerless. That’s painful. And it’s in that moment when he realises that whatever elevated social status in Israel he may have had is nothing but illusion.”

The flimsy existence of Sami and his wife in Israel is augmented by the fact that nobody outside the village seems to care that they have disappeared. In their capitalistic Israeli life, they’re cast in disposable roles, chucked off so casually at any given moment and replaced by other cogs in the machine.

Kolirin links this very modern Palestinian experience, conversely, to the heritage of Jewish literature.

“It goes in line with lots of great Jewish writings like Kafka’s about the disposability of man,” Kolirin said. “The fact that one day you can simply have your life put in danger and nobody around you cares or does anything about it that it simply becomes banal. This is also how occupation works, in the most viciously banal daily fashion.”

No heroes

Unlike The Band’s Visit and his subsequent feature, The Exchange (2011), Let It Be Morning is Kolirin’s least formally rigorous film to date. Gone is the still framing, deadpan humour and mannerism of his early work, replaced by a more dynamic and less showy visual style informed by the characters’ relationship to one another.

'I don’t feel the urge to be as formally rigorous as before; don’t feel the urge to feel important anymore. Sometimes the lack of style is a style in itself'

- Eran Korilin, Israeli director

“It’s evolution in my cinema I guess, of me growing less concerned about style,” he said. “If certain emotions need more camera movement or close-ups, then why not? I don’t feel the urge to be as formally rigorous as before; don’t feel the urge to feel important anymore. Sometimes the lack of style is a style in itself.”

One of the most fascinating aspects of both the film and the book is the class division Sayed captures so vividly and shrewdly through the dialogue. A term the village inhabitants use frequently is “Dafawis,” a reference to the Palestinians of the West Bank whom they regard as lowly. This class division, as Kolirin points out, is also an upshot of the occupation.

“Jews are essentially a powerful minority controlling another weaker minority. The same power dynamics govern Arab Israelis’ relationship with their countrymen of the West Bank in a never-ending series of suppression,” Kolirin said. “What Kashua subversively illustrates is that every minority is destined to find another minority to exercise its power on [a clear reference to Nietzsche’s Genealogy of Morality]”.

The thorniest territory Kolirin has stepped into is what some observers may superficially deem an unflattering representation of Palestinians.

Like the book, there are no heroes in this story; resistance has been replaced by composed resignation; internal conflicts have mushroomed; and collective spirit is a token from a bygone era (“In this village, we can’t get two people together for backgammon,” one character comments).

What Kolirin does, however, is provide a deeply flawed, and thus profoundly humane, portrait of a relatable set of Palestinian characters. They have dysfunctional families, messy sex lives, unfilled desires, and an unshakable sense of loss that has been passed from one generation to another.

In creating these unruly, unheroic multi-dimensional characters, Kolirin has honoured Kashua’s text and by default his Palestinian compatriots.

The Cannes controversy

From the early stages in production, Kolirin was adamant on having an entirely Palestinian cast – a process aided by Suleiman, whom the director calls “his partner” in building the world of the film.

“I wanted my cast to be politically aware individuals who know the significance of the story. Since The Band’s Visit, I think I developed a good reputation inside the Palestinian community so I didn’t face any resistance from the Palestinian performers I approached for the film.”

And this was one of the main points of contention when, in the wake of events in Sheikh Jarrah and the subsequent Israeli aggression waged against Palestinians last May, the Palestinian cast of the film – all Israeli citizens – decided not to participate in the festival in July for its branding of the film as Israeli.

The Israeli government did not take well to the situation. The new Israeli minister of culture, Hili Tropper, asserted that artists “who knew how to ask the state for a budget to make films” were in no position to “be ashamed of Israel”.

While accusations were banded about on both sides, the film itself continued to garner more acclaim. On 6 October, Let It Be Morning swept the Ophir Awards, known as the Israeli Oscars, winning seven awards, including best director and screenplay for Kolirin, best actor and actress, respectively, for Alex Bakri and Juna Suleiman, and best supporting actor for Ehab Elias Salami.

Bakri and Suleiman, both of whom are now living in Germany, did not attend the ceremony and released separate statements condemning “the efforts being made to wipe out the Palestinian identity” as the latter put it. (link?).

Salami, who did attend the ceremony, delivered a more tempered speech: “I have a dream, and that dream does not harm humanity … It’s in two acts - first, a just peace for the Palestinian people; the second act is a calm life, a peaceful life, a creative life for the citizens of the [Israeli] state.”

The statements of Suleiman and her co-stars continue to raise heated arguments about the position of Palestinian performers and Palestinian stories within the Israeli art scene.

When the dust settles, however, Let It Be Morning may finally be recognised for what it is: a daring, fresh and atypical snapshot of Israel-residing Palestinians torn between a flailing Palestinian persona and an alienating Israel adamant on perpetually shunning them.

“Would you mind if the film is dubbed 'Palestinian'?” I asked Kolirin.

“I have no problem with that, no,” he said. “I’m a Jew by heritage. I’m a different Jew from my father, and my father is a different Jew from his grandfather. I’m an Israeli by passport and I have nostalgia for a certain Israeli culture and I’m in big conflict with actions of my government. I’m also a Mediterranean – a child of this region.

'It was a terrible time for Palestinians in Israel. They were attacked... And then came the invitation from Cannes and it was just inconceivable for them to simply go and party'

- Eran Kolirin, Israeli director

"I’m all of these things. And I make a movie about a story that moves me with people I like. So you can call the film whatever you want. If you want to call it Palestinian, I’d be humbled and thankful.”

As we finished discussing the film, I couldn’t help asking Kolirin the one question that has been hovering on everyone’s mind: what happened in Cannes?

“It was a terrible time for Palestinians in Israel. They were attacked. There were militias of settlers backed by the government inside Palestinian neighbourhoods bullying them. The son of cast member, Izabel Ramadan, had the door of his house marked as a Palestinian. It was crazy.

“And then came the invitation from Cannes, and it was just inconceivable for them to simply go and party in there. It just didn’t feel right and I naturally understood their decision not to go.”

Still, Kolirin said he did wish they would have attended the festival, raised their Palestinian flags, and said whatever they wanted to say. The cast eventually opted to make a statement instead, which he publicly backed.

The cast’s statement intended to provoke a discussion regarding what constitutes an Israeli film and what doesn’t. In the case of Let It Be Morning, should the source of finance solely designate the branding of a Palestinian story based on a Palestinian novel and fronted by Palestinian performers as Israeli? And if yes, then why? Who sets these rules? Who determines the identity of the film, and on what criteria?

“I love that these discussions are arising. I think the question is absurd to begin with. Movies do not have identities; films are citizens of the screen. Our identities are always complex: I don’t think the word Israeli covers my entire identity. This question is forced upon us by the propaganda system,” Kolirin said.

“The term 'Israeli film' has no meaning. Have you ever seen Scorsese going on stage to present 'his American film'? Categorisation is a fluid question, and the importance of the cast’s statement is that it does tackle this question.”

The hostile reaction in Israel to the statement is rooted in the cast’s paradoxical identity: Palestinian citizens who are legally considered Israelis and who pay taxes to the state of Israel. Their struggle, ironically, is thus no different than their characters’.

At the end though, what comes across on screen is a picture made with a lot of love that stands as mirror to an underrepresented facet of the Palestinian experience, and a subtle, piercing censure of the crushing impact of the Israeli occupation.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].