Egyptians in New York: The untold stories of early immigrants to America

In the early days, Sami Boulos and a handful of Egyptian friends and acquaintances used to gather in an apartment in Manhattan once a month.

Hosted in the home of Saba Habachy, Egypt’s former minister of commerce and industry, they momentarily transported themselves back to their native country, while dishing out servings of food that reminded them of home, like macaroni bechamel – an Egyptian staple based on the Greek dish pastitsio.

They were among the first Egyptian immigrants to the US, and as good ambassadors of their country the gatherings would not be complete without the whole package: they watched documentaries about the pyramids; invited researchers to deliver lectures on archaeology; listened to music, and screened movies and photographs from recent visits to Egypt.

“There was really a sense of community, a sense of closeness, because in the late 50s and early 60s [they were] a small number,” Michael Akladios, an Egyptian historian at the University of Toronto Mississauga focused on oral history and immigrant adaptation, tells Middle East Eye.

They were united by their shared experience of being expats, but their backgrounds were varied.

Boulos had only started working for Egypt’s Ministry of Education as a school inspector in Cairo in 1951, a decade after completing his undergraduate degree. Then, in 1955, he was offered the opportunity to travel on exchange to the US, which he readily accepted.

Thanks to a grant from the US Office of Education, a 35-year-old Boulos arrived in New York alone in 1957 for his doctorate. He left behind his family, expecting to return to Egypt once his two-year temporary migrant visa expired.

But then Boulos decided to stay on permanently. He secured a teaching position at the State University of New York in 1959 and applied for exit visas for his wife and child to join him.

Given that the US didn’t relax immigration restrictions until the late 50s and early 60s, when it abolished the discriminatory national origins quotas, Boulos and his family became one of the earliest Egyptian immigrants to the country.

Back then, on a day off, a recent arrival to the US might sit by the phone all day, waiting for a call, before the days of the mobile phone

At that time, Akladios estimates that there were between 100 and 200 Egyptians in the US, based on the American Immigration Services Records, almost all Coptic.

They greeted each other on arrival after coordinating by phone or mail, and stayed in regular contact. Those without direct contacts in the country would usually arrive with a letter of introduction and an address given to them by an elder or religious leader back in Egypt.

Boulos’ wife, for example, would stay up late chatting to her friend, Saba Habachy’s wife Jamela, on the phone. They would discuss where to find certain spices, how to cook traditional Egyptian dishes with only the ingredients available in the US, and how to raise their children, who were going to American schools and learning English.

Back then, letters and phone calls kept them connected with Egypt, but Akladios notes that it was a far more arduous process than today.

Letters could take a while to arrive, and they would often wait anxiously to hear news from family or friends. Similarly, phone calls were scheduled well in advance, often by mail. On a day off, a recent arrival to the US might sit by the phone all day, waiting for a call, before the days of the mobile phone.

Arriving in New York City

Four years after Boulos’ arrival, on 4 June 1959, friends Elhamy Khalil and Atef Moawad arrived in New York aboard the German ocean liner SS Columbus, with a visa intended for a maximum period of five years of study. The 24-year-olds Khalil and Moawad, who had studied medicine together at Cairo’s Fouad First University, left Egypt with only $60 in their pocket.

To Khalil, the trip was an adventure - visiting a country he had only ever read about in books and seen glimpses of in movies. Their journey by boat was filled with excitement.

Nearing the docks in New York, 'everybody went on the deck of the ship and clapped when we saw the Statue of Liberty'

- Elhamy Khalil, early Egyptian immigrant to the US

Nearing the docks in New York, “everybody went on the deck of the ship and clapped when we saw the Statue of Liberty,” Khalil recalls, in Akladios’s forthcoming book Ordinary Copts: Ecumenism, Activism, and Belonging in North American Cities.

For Khalil, that “was the beginning of an adventure. It was amazing!”

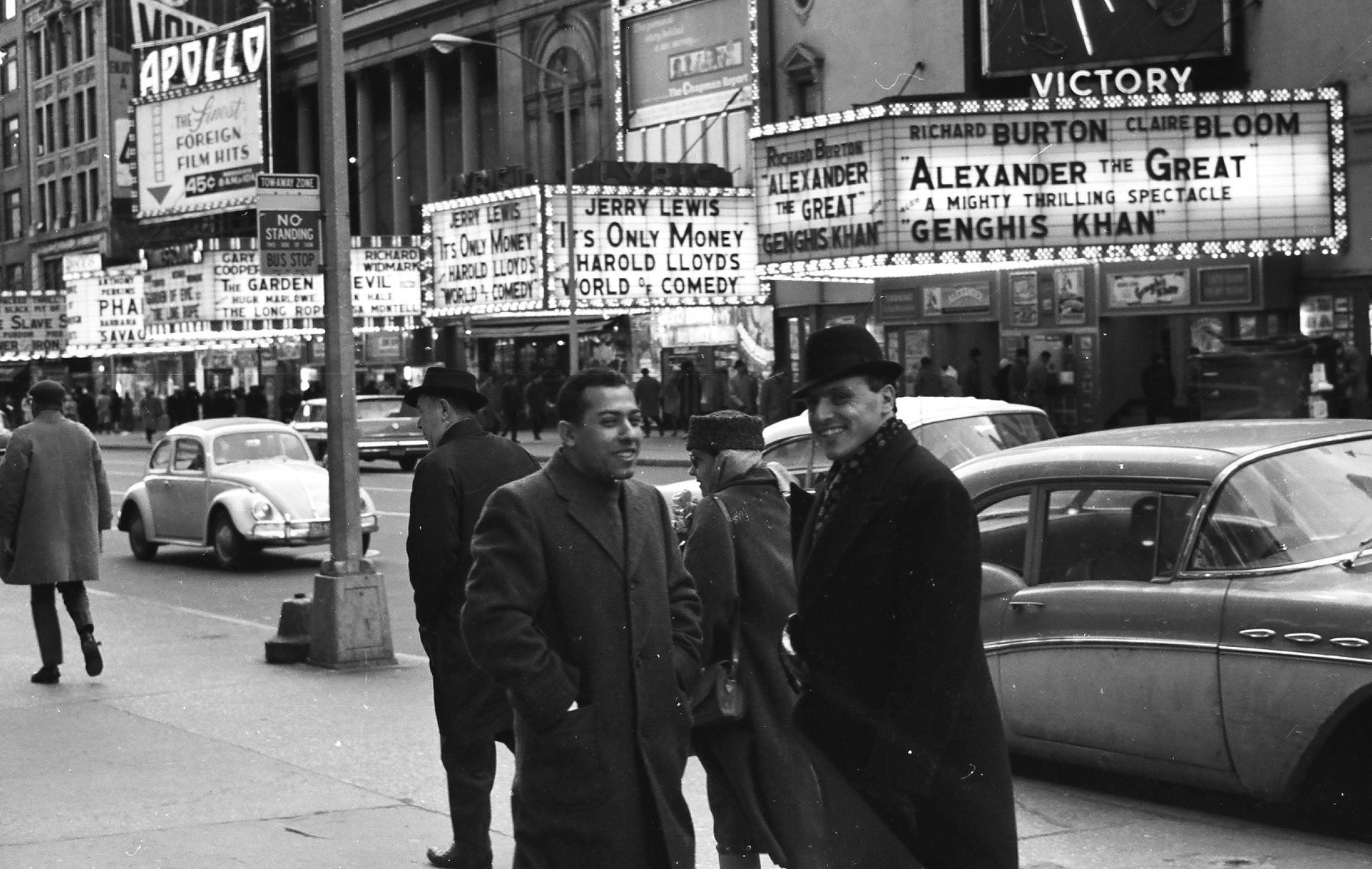

The pair secured accommodation at a hostel on 34th Street, near Times Square, for just two dollars a night. As they wandered the streets of New York, they discovered a rotisserie selling a whole chicken for 99 cents, which, along with a baguette from a local bakery, was their food for the day.

They spent a little more cash on museums and some of the city’s sites, including the Radio City Music Hall. For a dollar, they enjoyed a whole day full of shows.

“For Egyptian professionals from a bustling metropolis like Cairo, the cityscape or latest fashions were not a new sight,” Akladios said. “Rather, the culture shock was experienced when using unisex bathrooms in the hostel, listening to a street-corner preacher openly evangelise, and shop amidst the abundance and extravagance of department stores.”

In the end, Khalil and Moawad only spent a few days in New York. Money was running low, and after returning from a conference in Chicago it was time for them to separate and head off to their respective universities.

Khalil then moved to Newark, the most populous city in the state of New Jersey, and Moawad to the neighbouring city of Elizabeth, also in New Jersey, where they began their residencies at university hospitals. Yet they still gathered with other Egyptian immigrants on weekends when they were not on call.

An archive of Egypt’s diasporas

Stories and memories of migrants from Egypt like Boulos, Khalil and Moawad now rest in the Clara Thomas Archives of York University, in Canada. The first collection of its kind, it documents the life and the histories of Egypt’s migrants, and it can all be accessed in-person.

The repository is cared for by Egypt Migrations, a non-profit archival, educational, and community outreach organisation aiming to preserve and provide open access to source materials on the experiences of Egypt’s migrants and their descendants. The team is also slowly working on digitising some of the collections.

“It’s these little, everyday stories that had always attracted me to do the research I do, and the work we do at Egypt Migrations,” says Akladios, its founder and executive director.

Egypt Migrations first began in 2016 as the Coptic Canadian History Project (CCHP). Back then, Akladios was researching the Coptic Christian community in Canada and the United States for his PhD.

After he realised that there was no archival material about Egypt's migrant community that could help with his research, he decided to establish an organisation dedicated to preserving and promoting the histories of Coptic immigrants from Egypt in Canada.

In November 2020, following his dissertation defence, Akladios decided to reimagine the initiative and to be more inclusive of all Egypt’s migrants. The result was Egypt Migrations, which came about as a way to document, preserve and promote the diverse experiences of all Egypt’s migrants in their local communities.

“In my mind, the value is in capturing these little, mundane events and things that make up the larger picture, as opposed to talking about a spiritual leader or a politician,” says Akladios.

From Egypt to Brazil

One of the best-documented communities by Egypt Migrations so far is that in Canada and the US. Another group of Egypt’s migrants to which the organisation has recently devoted its attention through a collection of oral histories is that of Brazil.

There, the arrival of Egyptians took place in several waves. One of the most important of which was in the 50s, when the late Egyptian president, Gamal Abdel Nasser, expelled many Europeans and Jews from Egypt, says Diogo Bercito, a Brazilian journalist and scholar focused on Arab migration to Brazil, and the interviewer for this collection.

Among them was Jacques Sardas. Born in 1930 in Alexandria to a Sephardic Jewish family, Sardas and his relatives moved to Cairo when he was still a child. There, he held a variety of jobs, including at a department store, and in 1956 he married a woman named Esther Pesso, whose parents came from Yugoslavia and Greece.

As a result of the rise of anti-Semitism in Egypt following the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948, and the Suez Canal crisis in 1956, Sardas and Pesso, who was pregnant with their first child at the time, moved to Sao Paulo.

Only three days after their arrival in Brazil, Sardas managed to get a job at a bank, even though he still couldn’t speak Portuguese or English and was living in a refugee camp. Three months later, he was hired at the American tyre maker Goodyear.

Their arrival in Brazil, Bercito notes, was not easy. “They did not know the country, its language, or its people. It was a journey into the unknown,” he tells MEE.

One of the things that helped them in Sao Paulo was a network of other Egyptian Jews that had migrated to Brazil before them, and who helped them settle down.

'A lot of Brazilians don’t even know there is an Egyptian community in Brazil, and the stories are not recorded'

- Diogo Bercito, Brazilian journalist and scholar

Over time, Sardas rose from file clerk to sales manager and he was eventually transferred to Paris, where he became president of Goodyear France, and finally to Ohio in 1974.

Sardas never returned to Egypt. In fact, Bercito notes that his exit visa made it clear he was not allowed to return. He retired in 2008, and now lives in Dallas with Pesso, their four daughters and their eight grandchildren.

Yet, like other Egyptian migrants, he still maintains his emotional connection with the homeland, mostly through food: “During the interview, he mentioned dishes like foul, falafel, and kofta, with a smile on his face.”

Documenting the lives of migrants is fundamental, Bercito says: “A lot of the stories of what happened to Syrian and Lebanese migrants [to Brazil] are lost because a lot of these people migrated at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th. A lot are already not among us, and did not transmit their stories.

“The same thing happens with Egyptians. A lot of Brazilians don’t even know there is an Egyptian community in Brazil, and the stories are not recorded.”

Migration to the Gulf

So far, Egypt Migrations has catalogued one metre of archival records and a set consisting of 3GB of digital material. Sixteen more boxes of archival material will soon be deposited in the Clara Thomas Archives, which have been closed for much of the time since the onset of the pandemic.

The documents include newspaper clippings, photographs, documents, letters, journals and magazines, and all come from family collections and personal records. As the organisation grows, it has also begun to direct its attention beyond the Americas; in January 2022, a collection of 10 oral histories of migrants in the Gulf is due to be released.

Mohsen El Shimy returned to Egypt before the 1991 Gulf War and when he returned for his work, he found his offices had been looted and destroyed

One of them is Mohsen El Shimy’s story. Born in Cairo in 1944, he graduated with an English degree and worked briefly with British Airways before deciding to move to Kuwait in 1966 to pursue a job in the Ministry of Education, Alya Osman, a student at New York University Abu Dhabi and the interviewer for the Egypt Migration Gulf series, tells MEE.

“Mohsen’s story is quite exceptional in that, although many Egyptians would move to Kuwait in the 1970s and 80s, the country was not a popular destination for expats when he moved there,” she says.

When he first arrived, landlines were not yet available and people had to book an appointment at the Central Communications Office to use the phones there.

El Shimy then returned to Egypt before the 1991 Gulf War for family reasons but found himself unable to travel back to Kuwait until the war was over. When he returned for his work, he found his offices had been looted and destroyed.

The country he remembered was also very different.

“He commented on the effect of the Gulf War on expats, feeling that the trauma of the experience made the Kuwaiti population much more reserved and may have led to greater xenophobia and less hospitality,” Osman said.

Despite this, El Shimy stayed in Kuwait on and off for 49 years, during which time he got married and had children. Throughout this time, he still found time to travel to Egypt regularly, and maintained connections with his family and children. And like many Egyptian migrants to the Gulf, Mohsen returned to Egypt in 2015 once he retired, and has never returned to Kuwait since.

“In many ways, his story embodies the transnationalism and cultural dexterity of so many Egyptians abroad and in the diaspora,” Osman says.

Referring to the other stories as well, she said that “the interviews tell stories of people’s aspirations and what encourages them to journey, what makes them able to put up with certain downsides of living abroad”.

“[Many] talked about loneliness, or xenophobia, or moving because they were aspiring for better lives for their kids.”

Egypt Migrations also aims to highlight the diversity of Egypt’s diaspora communities beyond boundaries of gender, class or generation, and on integrating varied and opposing voices. To this end, the organisation works with partner groups like Coptic Queer Stories, from California, and Progressive Copts, from Ontario.

“The most valuable part of Egypt Migrations to me is that it became - and with its growth it is becoming more and more - a place in which different people who are either critical or have been left out of the official narrative can come together and discuss what being Egyptian and being a migrant means to them,” Miray Philips, a PhD candidate at the University of Minnesota and the organisation’s former editor, tells MEE.

“Egypt is one of the most labour-exporting countries in the world, and we have a huge Egyptian population that lives outside of Egypt. But they are not always seen as part of the social fabric either of Egypt or the countries they migrate to,” Osman said.

“[Egypt Migrations] is creating a document of these experiences that millions of Egyptians have had,” she added.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].