How Tunisia inspired Kandinsky and enabled expressionist art

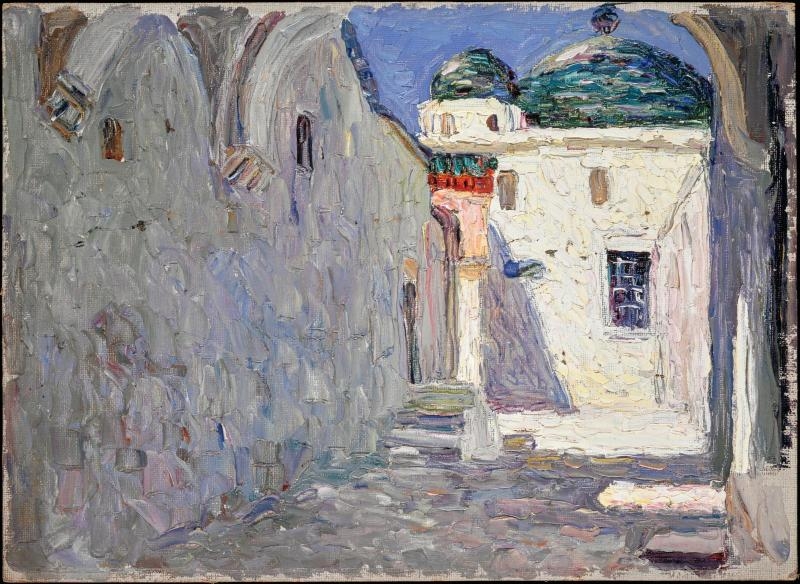

The traditionally studded doors of Tunisia’s Sidi Bou Said village would have appeared dream-like to Vasily Kandinsky's artistic sensitivity.

For the Moscow-born painter, white symbolised the harmony of silence and blue was a heavenly colour.

Having arrived in the country with his German partner Gabriele Munter on Christmas Day in 1904, Kadinsky spent the next three months in Tunis, first at the Hotel Saint Georges, then the cheaper Hotel Suisse.

Their perceptive photographs, sketches and gouaches capture glimpses of Tunisia’s capital city and beyond. The pair also briefly visited Sidi Bou Said, Hammamet, Sousse and Kairouan.

Even before he arrived in North Africa, Kandinsky was already making a name for himself. He had shown at the Salon d’Automne in Paris in 1904 and taught in Munich between 1901 and 1903, where he met Munter, a fellow artist. However, Kandinsky’s artwork had yet to evolve into the elaborate abstract compositions for which he is now famous.

In Tunis though, we see in his brush strokes the waning influence of neo-impressionism and an increasing attention towards colour, permeating from the everyday motifs he chose.

Life in the city, though relatively brief, would have a lasting impact on his works even decades later.

Munter’s camera was a shared accessory that immortalised street life and memories. Years later, these photographs would help Kandinsky revive the colours and scenes of Tunis from afar, in the manner of postcards or a first sketch.

Kandinsky recalled in 1938 how he had felt under the "strong impressions of the phantasmatic environment" in Tunisia. Munter affirmed this view in 1960, after Kandinsky’s passing, stating that he "already expressed a great interest in abstraction" when in Tunisia.

Specifically, Islamic art and Islam’s religious prescription against the pictorial representation of the divine may have further prompted Kandinsky to experiment with new forms and colour, to begin questioning the power of the non-objective and explore the idea of "form-feeling" that the painter would later develop, notably in his ground-breaking art theory volume, On the Spiritual in Art.

'Hearing' colour

Less than a week after Kandinsky’s arrival, Japanese forces seized Port Arthur and the Russo-Japanese War continued its uncertain, dangerous course. It’s amidst deep worry for the fate of his compatriots, including his enlisted brother, that Kandinsky attempted to engage with his surroundings, limiting contacts with outsiders.

He and Munter arrived in Tunis, a generation after the establishment of the French protectorate of Tunisia, in 1881. Unlike Algeria, the Bey remained in nominal authority while France, through its highest representative, the resident general, took over diplomacy and finances, as well as stationing its army on Tunisian soil.

The pair witnessed traditional celebrations during their stay - of Eid Al Adha for instance, which Kandinsky sketched in his Fete de Moutons (Tunisian Sheep Festival, shown at the 1905 Paris exhibition, now in the Guggenheim’s Founding Collection). The painting portrays recognisably Muslim and Jewish people, including children, near a modest ferris wheel. The festive event, a fete foraine or travelling carnival, seems to have taken place in Halfaouine Square and is blessed by a rainbow.

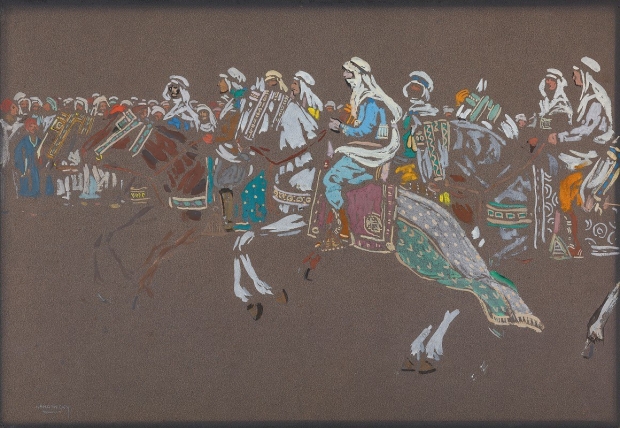

In her photographs, Munter also captures the equestrian "fantasia", in which skilled horse riders were selected to parade the streets of Tunis holding rifles. In that image, a prominent Tunisian flag is held by one of the riders. Another rider follows him, this time holding a French flag of the same size.

Kandinsky’s rendering of the scene conveys movement and folklore. In Arab Cavalry, published in 1905, he strips away historicity and space, and what remains evokes the timelessness and resonance of the wild steppes of his native Russia.

What they see matters as much as what stays hidden from them and absent. As non-French Europeans, their gaze is largely confined to public spaces - to alleyways, to squares such as Halfaouine, Bab el Khadra or Bab Souika, or parks such as the Belvedere.

Nevertheless they remain attentive to Tunisia’s diverse social and cultural fabric, for instance painting Black subjects, daily workers, and Sufi Marabouts, the latter being the tombs of local saints, religious guides or founders of a zaouia (religious establishment).

Orange Sellers (1905) is based on the Marabout of Sidi Sliman, which no longer exists. The painting contains touches of vivid colour and the placement of oranges like notes on sheet music in front of the Marabout highlights the idea that Kandinsky could "hear" colour as he possessed a rare ability called synesthesia.

Kandinsky and Munter works during their visit to Tunisia demonstrate that they were more interested in the contemporary Arab soul of Tunis than its classical past and the ruins of Carthage. They visit the Bardo Museum, located in a 19th century Beylik palace, and not the Byrsa Hill, the site of an ancient Phoenician citadel, which was the heart of Carthage before its destruction by Rome.

They painted the modern villas of Tunis and the tombs of the Beys, capturing a city at a standstill and transformation, between tradition and modernity. Even long after his sudden return to Europe due to family matters, Kandinsky regularly went back to revisiting his Tunisian memories, for example in the visually more daring Arabs I (Cemetery) painted in 1909.

Impact on other artists

Kandinsky and Munter created the Blue Rider (Der Blaue Reiter) movement a few years after leaving Tunisia, in 1911, with other artists, such as Marc Franz, Paul Klee and August Macke. The symbol of the horse and its rider for this avant-garde group takes a spiritual connotation, one of artistic freedom, and inevitably refers to the Tunis cavalcade in its essentialised form.

Tunisia re-emerges in Expressionist art history, via two other artists affiliated with the Blaue Reiter, the Swiss Klee and German Macke. With a third friend, Louis Moilliet, a compatriot of Klee's, who had floated the idea of the trip since 1913, the artists visited Tunisia in 1914 on the eve of the First World War. Klee consigned his impressions in a diary, which provides us with rich insights on his artistic practice as well as daily life.

Kandinsky and Munter transcribed the domination of the French in Tunisia in symbolic terms, through flags and the official "Republique Francaise" insignia that would be included in (relatively few of) their paintings and photographs. Klee had also noticed the fleeting "Frenchness" of the protectorate.

The Tunisian independence movement before war mainly occupied the elite. In 1907, the Young Tunisians formed a political party and tried to increase the outreach of their message of liberal reforms and greater Tunisian participation in the country’s affairs with the launch of the bilingual newspaper Le Tunisien (Arabic edition launched in 1909).

With mounting social unrest in the context of the recent Italian takeover of Tripoli, further compounded by a French decision to regulate land ownership in a cemetery, French authorities declared a decade-long state of emergency from 1911 which forced the editor of Le Tunisien, Ali Bach Hamba, into exile. At the outcome of a trial, the French guillotined several pro-nationalist protesters.

This helps in understanding Klee’s caustic remark when he wrote in his diary on Easter Monday, 1914, just before travelling to Hammamet: "Tunis is Arab in the first place, Italian in the second, and French only in the third. But the French act as if they were the masters."

Klee encounters French people, who were mostly arrogant, mocking - the three artists were presumed to be Germans and treated as such - and unwelcoming. He describes in later pages, as Kandinsky had also mentioned, the rickety trains and a dilapidated highway - not so advantageous for the image of the French colonial project which was to modernise public works among other "civilising" feats.

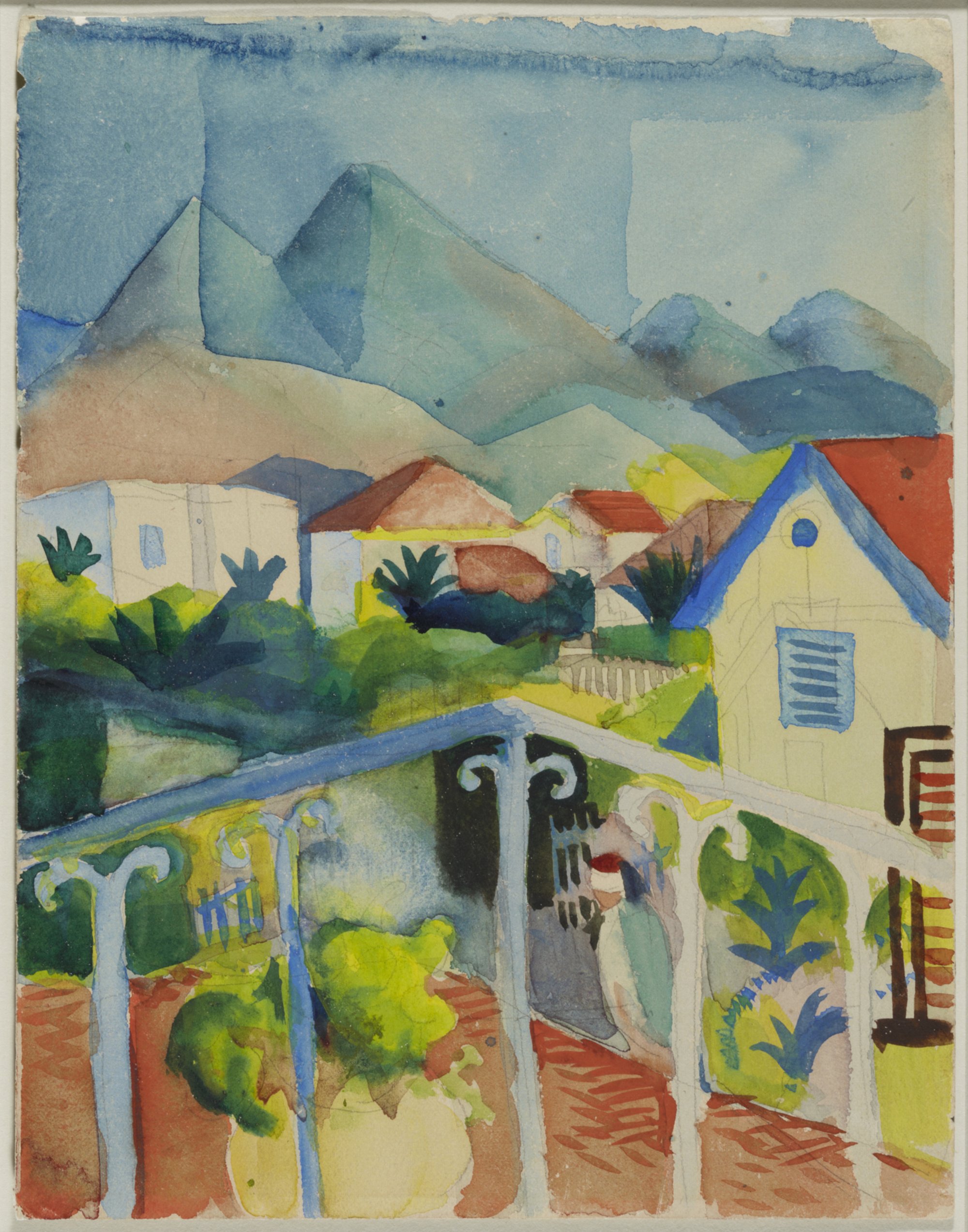

Klee was attracted to architecture, cafe life, as places of socialisation, gossip and storytelling; he often painted in Halfaouine Square. His interest encompassed vistas and gardens. In Tunis, the three men stayed with a Swiss doctor and his wife, who also owned a secondary home in Saint-Germain, today’s Ezzahra, less than 13 miles away from Tunis on the seaside. In Ezzahra, in a villa not far from the beach and close to Boukornine mountain, Klee and Macke drew evocative watercolour sketches.

In Saint Germain near Tunis (1914), Macke stylises Boukornine in blue, pyramid-like forms in the backdrop of a panorama, which includes both Arab and French houses amongst an ebullient flora.

From a similar-looking vantage point, Klee’s chromatic values are obliquely deeper, the hues less saturated and his watercolour, View of St. Germain (1914), suggest a subdued reverence.

We explore Klee’s journey as a geography and as an inner progression, towards works that highlight colour and abstraction, such as in Hammamet with its Mosque (1914) and Before the Gates of Kairouan (1914). In these two luminous watercolour paintings, we feel the stroke of a blinding Mediterranean high-noon sun and the awe of a spectacular, kaleidoscopic landscape. His exploration culminates in density, richness, depth and saturation in In the Style of Kairouan (1914), painted shortly after his return from Tunisia. Years later, like Kandinsky, he would remember Tunisia and its southern gardens.

Tunisia uniquely altered Klee’s artistic journey, which he likened to an "intoxication". Both Macke and Klee encountered local artworks and presumably interacted with their styles.

It was in the holy city of Kairouan that Klee discovered colour and experienced almost an epiphany.

"Colour and I are one. I am a painter," he wrote on 16 April 1914, leaving Tunisia shortly after, explaining: "I had to leave to regain my senses."

Macke was killed in action in France early during the war in September 1914.

Championing inner expression

Klee and Kandinsky would teach together at the influential Bauhaus school, which was formed in Germany after the war. The institute emphasised modern art theory and also taught other disciplines, such as design and architecture.

Following the rise of Hitler and the confiscation of some of their artwork, which were considered "degenerate" by the Nazi regime, both artists eventually left Germany.

A 2014 exhibition marking the 100-year anniversary of Klee, Macke and Moilliet’s trip to Tunisia underscores the contribution Tunisia made to European Expressionism.

The combined legacies of Kandinsky, Klee and Macke, as pioneers of the non-objective, and champions of using the canvas as a gate towards inner expression and the spiritual, is immense and extends a sphere of influence over artists such as Mondrian, Rothko, Pollock and others.

And behind this chromatic liberation, somewhere, is the memory of Tunisia’s shores, its markets, towns and people and the distant drums of a darbuka reverberating in strokes, shapes and gradients, colliding in beauty beyond words and an un-representable truth.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].