While you were sleeping: The importance of dreams in Middle Eastern culture

Arms outstretched, gliding through a deep-plum sky; running from monsters known and unknown; fights in which a punch never quite seems to land with any force; and finally, a sudden jolt, and you’re back in your bed and in a reality where the laws of physics matter again.

Given the defining role they have played in human civilisation, from religious experiences to scientific revelations, dreams are perhaps one of the least understood human phenomena.

Explanations for why we experience dreams range from the purely material - a type of processing mechanism for memories; to the mystical, where dreams serve as a gateway into the subconscious and all the mysteries contained therein.

In The Red Book, the Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung wrote: “Dreams are the guiding words of the soul.

“Why should I henceforth not love my dreams and not make their riddling images into objects of my daily consideration?”

'Dreams are the guiding words of the soul'

- Carl Jung

For Jung, dreams were a platform where symbols, both common to all humans and unique to the individual, arose to warn the dreamer of problems in the conscious life. His contemporary Sigmund Freud believed every aspect of a dream carried a symbolic significance, no matter how outwardly trivial it seemed.

Many scientists reject such explanations, arguing Jung and Freud drifted too deep into unfounded speculation, a charge their supporters continue to reject today.

Irrespective of scientific explanations, there’s no avoiding the role dreams have played in the development of human history.

The Egyptian president, Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, purportedly said he dreamt of becoming leader of Egypt, before overthrowing the country's first democratically elected president, Mohamed Morsi.

Further back, both the Bible and the Quran describe dreams by prophets and other figures, which believers say contained instructions or warnings from God.

Book of dreams

While dreams are likely to have influenced the formation of religious beliefs many thousands of years ago, the earliest documented works on the topic are found in Ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt.

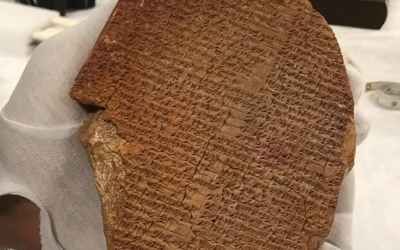

The Epic of Gilgamesh, which was first compiled in around 2100 BCE, is thought to be the oldest epic poem and contains the earliest known dream description.

The epic follows the semi-mythical King Gilgamesh of Uruk as he tries to find the secret of eternal life and battles the gods in the process.

In one scene, Gilgamesh describes a dream in which he encounters a meteor that falls to earth. His goddess mother, Ninsun, interprets this as the impending arrival of a close companion, which later turns out to be Enkidu, a wild man created by the gods to stop Gilgamesh from oppressing the people of Uruk, and who later becomes Gilgamesh’s best friend.

The tablet describing the episode was found in the Library of Ashurbanipal in around 1852, along with a set of 11 other tablets that described dreams and their meanings. These were later compiled into a book known as Iskar Dzaqiqu, and translated in 1956 by Assyriologists into The Assyrian Dream Book.

Ancient Assyrians believed dreams were of three types - messages from the gods, prophecies, or expressions of the dreamer’s own psychology - with later civilisations following a similar classification of dream categorisation.

Ancient realms

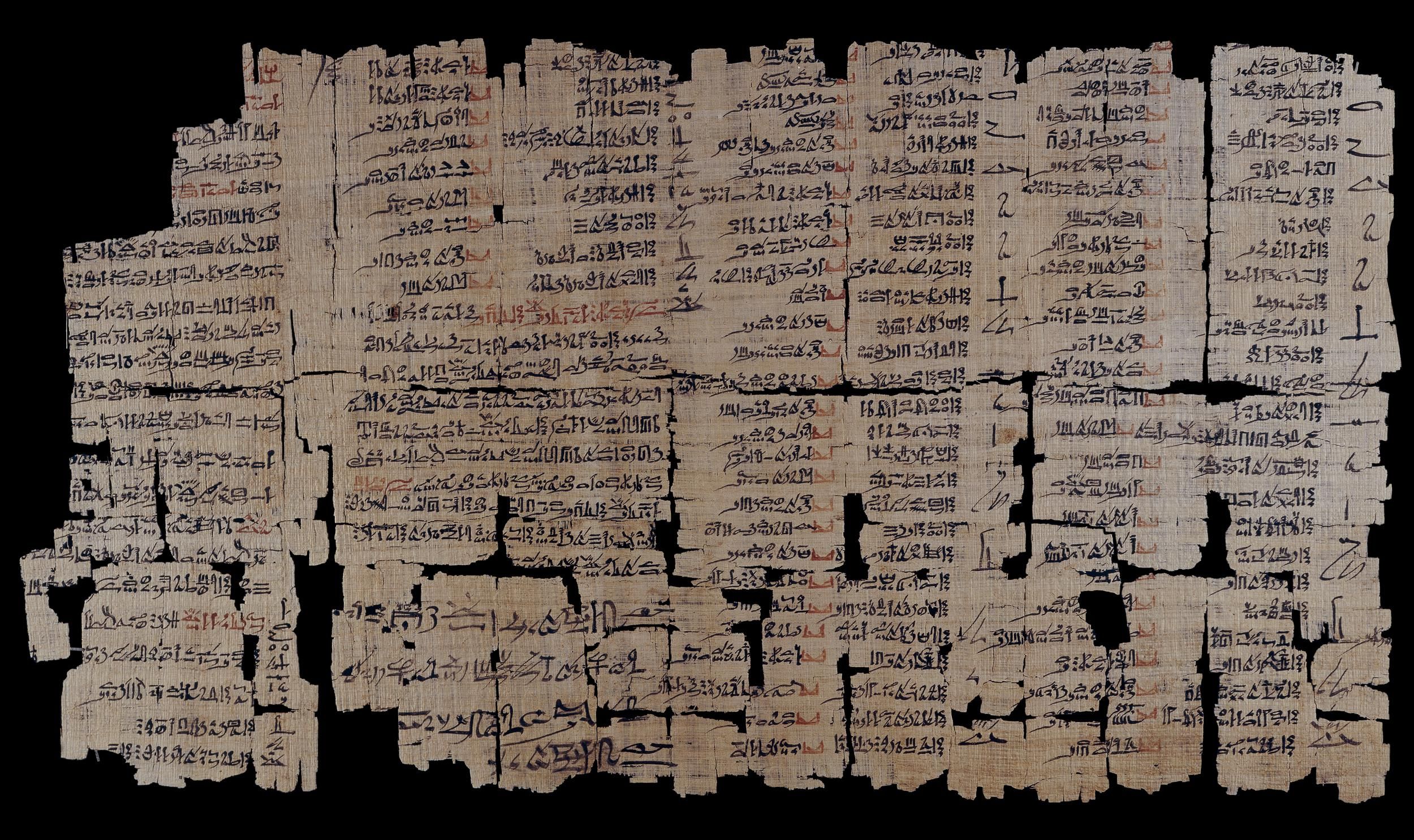

The subject of dreams was also important enough for the Ancient Egyptians to have a dream book of their own.

Written on papyrus in hieratic script (a form of cursive hieroglyphics) and dating to somewhere between 1279 and 1213 BC, during the reign of Ramesses II, the book begins with the words, “If a man sees himself in a dream”, followed by 108 descriptions of dream events and their meaning.

The visions are interpreted as either good or bad and contain short interpretations.

Some examples include:

“If a man sees himself dead this is good; it means a long life in front of him.”

“If a man sees himself putting his face to the ground this is bad, it means the dead want something.”

Some dreams were straightforward and were clear to decipher, but the Egyptians’ fascination with oneiromancy, or the interpretation of dreams, led to greater study and soon oracles were performing specific rituals to induce dreams.

Dream incubation was a way to try and ensure specific dreams or visions, or seek an answer to a particular problem through a dream. Forms of the ritual have been practised by Mesopotamians, Greeks and Jews, and the Muslim Istikhara prayer (prayer for guidance) has also been described by some as a method of dream incubation.

In Ancient Egypt the process of dream incubation would involve the dream interpreter going to a temple, like the one at Dendara, and performing a series of rituals (such as sacrificing an animal or fasting), before sleeping in order to dream an explanation for an earlier dream.

Sufi Muslims incorporate a type of dream incubation in their worship or practice lucid dreaming in order to reach higher consciousness. Ibn Arabi, a 12th century Sufi philosopher, described the "great benefits" in training oneself to experience lucid dreams.

Divine wisdom

It is clear from the importance placed on dream-related rituals that for ancient peoples and for many religiously inclined people today, dreams are a gateway into a spiritual realm.

According to the Jewish tradition, from which other Abrahamic faiths descend, dreams were one mode of communication between God and his prophets.

In the biblical account, Abraham was instructed by God to sacrifice his son Isaac in a dream and the story of Joseph involves both him interpreting the dreams of others and his own.

In Judaism, sleep is seen as a veil between the living world and the one beyond of spirits and angels, dreams were a way to access divine wisdom.

In Christianity, Joseph, the husband of the Virgin Mary, was said to have been considering leaving his wife upon discovering her pregnancy. He then had a dream where an angel ordered him to stay.

And in Islam, the Prophet Muhammad told his companions that after his death the only form of prophecy and guidance would come in the form of true dreams and visions, called ru’ya.

Years later, the 13th-century scholar and philosopher Ibn Khaldun divided dreams into three categories; clear dreams and visions, which come from God; dreams from angels, which have a hidden meaning or message that may require interpretation; and confusing or bad dreams, which are attributed to the devil.

Scholarly interpretation

Demonstrating the importance placed on dreams in early Islam, compendiums of dream meanings and symbolism were compiled by Muslim scholars to help in interpretation.

According to John Lamoreaux, an academic specialising in early Islamic studies, there were 63 dream books written in the first 450 years of Islam, an indication of their widespread popularity, although few have survived.

The earliest surviving dream book is by the Persian scholar Ibn Qutaybah. His work called On the Interpretation of Dreams (Ta῾bir al᾽Ru᾽yā) was written in the ninth century and outlines nine methods of interpreting dreams, including “interpretation through opposites” (Ta’wil bil did wal maqlub) - so giving birth would mean dying.

1. Ta’wil al asma - interpretation by etymology. If you dream of a quince (safarjal), then it means a journey (safar)

— Ali A Olomi (@aaolomi) September 4, 2019

2. Ta’wil bil ma’na- interpretation through meaning. If you are given a drink, then you will have children because water is a blessing and gives sustenance.

Other notable Islamic dream interpreters include the ninth-century scholar Ibn Sirin and the 10th-century writer Abdullah Ibn Abi Zayd al-Qayrawani.

Such traditions were not unique to Islam or the other Abrahamic faiths.

Zoroastrians have their own rules, including one which insisted a dream could only be accurately interpreted on the same day as its occurrence. The Sifat-i-Sirozah is a detailed compilation setting out how dreams are to be interpreted and classified according to the day of the month.

For example, the third day of the month is the day of Ardebehist, the guardian angel of fire. Dreams had on this day will not come true. But the sixth day of the month is the day of Khurdad, the angel presiding over water and vegetation. If a dream is had on this day, it will come true before the month is over.

Despite these rules, the art of interpretation retained a degree of subjectivity and the importance of choosing the right dream interpreter is lightheartedly addressed in an anecdote from the Middle East. The same dream, of teeth falling out, is interpreted for a king in two different ways. In one the interpreter warns the monarch that his family will die before him, in the other he is told he will outlive his family. One leads to the interpreter being punished and the other leads to the interpreter being rewarded.

While dream interpretation may not be the career option it used to be, there is still evident interest in the topic.

Psychoanalysts like Freud and Jung have their followers in the Middle East, as they do elsewhere, but there are also practitioners whose methods are rooted in either religion or contemporary forms of superstition, such as astrology.

In Saudi Arabia, more established dream interpreters have warned of the dangers of approaching scam artists promising to unlock subconscious secrets in exchange for money.

There have also been instances of charlatans using the information they glean about a dreamer’s personal life to blackmail them.

Paralysed and unconscious

What does modern science tell us about dreams?

We all know sleep itself is important for a healthy life, with sleep deprivation used as a form of torture.

The average person will spend around a third of their life sleeping, and are believed to experience four to six dreams a night, which occur during moments of rapid eye movement (REM).

While dreaming, our bodies are described as being paralysed but our brains continue to be active.

Using electroencephalogram (EEG) scans, scientists can tell when we are dreaming. They can also tell that our brains are responding to visual and auditory stimuli that are not necessarily present in the waking world around us.

But beyond that, the field of dream study is subject to speculation and theorising, with no confirmed ideas on why we dream.

The rather more prosaic and rationalist theory is that dreams help us process the day’s events and store important memories and experiences.

For Jung, the dream state was that in which the subconscious aspects of our mind awoke.

The deepest of these levels was the “collective unconscious”, an aspect of our mind common to all humanity and whose symbols, instincts and archetypes were formed over the course of human evolution.

This residual consciousness, Jung argued, explained why so many disparate cultures shared the same symbols and even why so many of us share variations of the same dream.

While unproven and arguably unprovable, the theory might explain the enduring popularity of dream narratives from Gilgamesh to the Bible.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].