Ghost towns, rockets and drones: Polisario’s war in Western Sahara

Polisario calls this the “liberated territories”.

At times soft and sandy, more often it’s a hardscrabble desert, where wiry shrubs poke out of the earth like knots stitching the land together. Goat herders languidly following their flocks were a common sight 12 months ago. For those seeking the traditional nomadic life, Polisario-held Western Sahara was a paradise, a land of limitless skies and quietude.

Today, that silence will be broken by a rocket attack, the latest raid in a year of sporadic conflict between the Polisario Front, a Saharawi national liberation movement, and Morocco.

This is a war fought at arm’s length, a conflict of artillery fire, attrition - perhaps the odd drone strike. But three decades of ceasefire were undone on 13 November 2020, and after so long, Polisario's energised fighters clearly desire more direct engagement.

“We are fighting to liberate our land from the Moroccan occupation,” says Mohammed Salem, the battalion commander leading the operation. “The Moroccan regime is a dictatorship.”

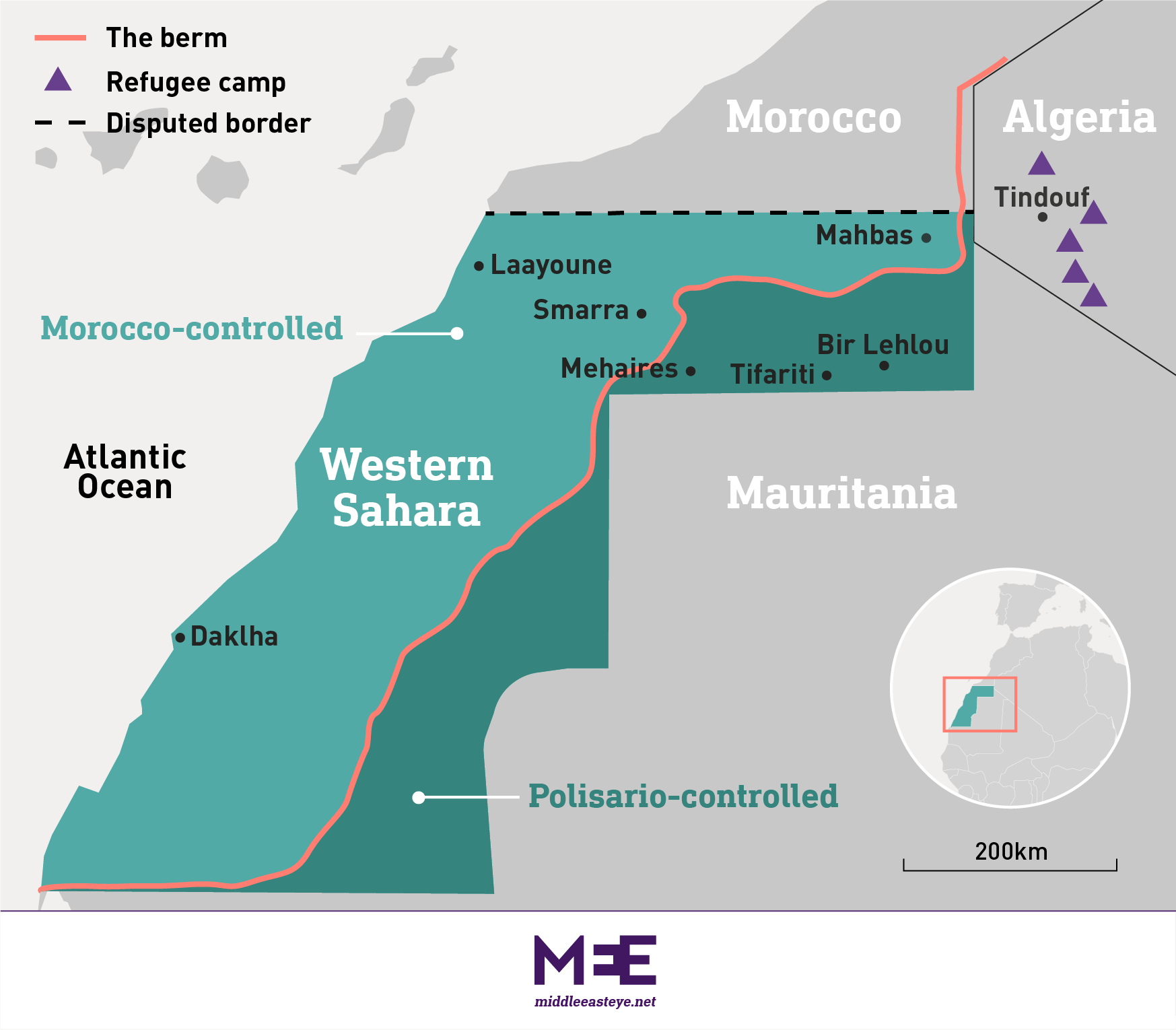

Polisario-held Western Sahara is a barely recognised statelet known as the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR). It lies in the 20 percent of Western Sahara that the movement seized from Morocco and Mauritania after Spain, the colonial power, exited in 1975.

During the past decade, Polisario has made a point of encouraging some of the 176,000 Sahrawi refugees living in camps over the border in Algeria to settle in this sliver of desert. But now the scattering of homes and tents that make up the SADR’s settlements lie empty.

In the town of Bir Lehlou, the porticos of an ochre-painted school are absent the patter of children’s feet. Hot pink exercise books lie browning on abandoned classroom floors.

Further south, in Mehaires, a hospital’s walls and bedsheets have taken a sepia tinge, dust and grime creeping in through the cracked windows. The oasis town’s market street, shuttered and silent, is a tumbleweed away from a Western shootout.

This land was far from bustling in the first place - no more than 10,000 people lived in its approximately 53,000 km2, an area the size of Greece.

But then Polisario declared war on Morocco and the evacuations began. Now only convoys of soldiers break the still. “Hundreds of families lived here, but more than 90 percent of people are now back in the camps,” says Mohammed Bega, a Polisario military commander.

These buildings have only been abandoned a year, at most. But in the Sahara, months age materials like years.

Sahrawis plan attacks on the berm

Time has been hard on the Sahrawis. Since the 1991 ceasefire began, they have seen Morocco develop Western Sahara’s towns and cities, settle its citizens there and win support from several African states and the Trump administration over its claim on the territory.

Western Sahara’s natural resources, its major urban centres and the coast are all held by Morocco - or rather, Polisario argues, occupied, according to international law.

In the meantime, Sahrawi refugees have waited for a promised referendum on independence that never came, languishing in the limbo of forgotten camps in a corner of Algerian wasteland. Maddeningly hot in summer, frosty during winter, little fresh produce makes its way to these Polisario-administered settlements. No surprise, then, that news of the ceasefire’s disintegration was received rapturously by the majority of Sahrawis in the Tindouf camps and “liberated territories”.

For those who fought in the 1975-1991 war, here was a chance to relive former glory. To the youth, the resumption of the conflict was the opportunity to write their own history.

Western Sahara explained

+ Show - HideWestern Sahara is a largely desert expanse (266,000 sq km) in the northwest of Africa that is bordered by the Atlantic, Morocco, Mauritania and Algeria. Its indigenous people are the Sahrawis, who mostly speak Hassaniya, an Arabic dialect.

The region was colonised by Spain during the late 19th century and later became known as the Spanish Sahara. Morocco, parts of which were also a former Spanish colony, has long made claims on the region.

In November 1975, King Hassan II of Morocco sent 350,000 civilians and 25,000 troops into what was still Spanish territory, as part of what became known as the "Green March".

Fearing that conflict with Morocco would destabilise the government at home, as it had done with other European colonial powers like France (in Algeria) and Portugal (in Angola), Spain rapidly departed Western Sahara, cutting a secret deal with Morocco and Mauritania, the latter of which also claimed close links to the area.

Signed in the last week of fascist leader General Francisco Franco’s life, the Madrid Accords removed the Sahrawis and their chief representatives, the Polisario Front, from the equation. Two thirds of the territory was given to Morocco, and one third was given to Mauritania.

When Morocco and Mauritania entered Western Sahara in 1975, war began with the Polisario Front, and thousands of Sahrawis were forced to flee to refugee camps in Algeria. Their place has been taken by Moroccan settlers, who have been incentivised to move into the region by Rabat and who now make up the majority of Western Sahara's population.

Polisario, which seeks independence for the territory and is backed by Algeria, defeated Mauritania in 1979. The land won in this war is now known to Sahrawis as the "liberated territories", a largely uninhabited stretch of desert to the east of Morocco's 2,700 km-long border wall.

A 1991 ceasefire broke down in November 2020. There has been sporadic fighting since then.

Timeline

1884: Spain declares Western Sahara a protectorate on 26 December. The Spanish meet immediate resistance from the Sahrawis.

1956: Morocco gains independence from France and Spain on 2 March.

1957: At the United Nations, Morocco makes its first modern claim on Western Sahara (certain treaties from the 17th and 18th centuries included Moroccan claims to some of the region).

1958: Spain creates the overseas province of Spanish Sahara on 10 January.

1966: Creation of the Harakat Tahrir, or the Movement for the Liberation of Saguia al-Hamra and Wadi al-Dhahab. It campaigns for a peaceful end to Spanish rule and self-determination for Western Sahara.

1970: A Harakat Tahrir protest in Laayoune on 17 June is brutally suppressed by Spanish forces, resulting in at least 10 deaths and hundreds of injuries. The movement disbands.

1973: Creation of the Polisario Front on 10 May to represent the Sahrawis.

1974: Spain announces on 20 August that it will hold a referendum to decide the future of the region in the first half of the following year. Morocco rejects the idea. The UN asks the International Court of Justice (ICJ) for an advisory opinion.

1975

16 October: The ICJ rules in a non-binding decision that while there were legal ties between Western Sahara and Morocco and Mauritania, these did not “establish any tie of territorial sovereignty”; also that such legal ties did not apply to "self-determination through the free and genuine expression of the will of the peoples of the territory”.

31 October: Morocco invades Western Sahara from the north.

6 November: At the urging of King Hassan II, an estimated 350,000 unarmed Moroccans cross into Sakiya Lhmra in support of territorial claims in an event that becomes known as the Green March (below). Spanish troops are ordered to let them pass to avoid bloodshed.

14 November: Fearing conflict with Morocco, Spanish support for Sahrawi self-determination falters. Under the Madrid Accords, Western Sahara is ceded to Morocco (the northern two-thirds of the territory) and Mauritania (the remaining south). While the deal states that the views of the indigenous population need to be respected, no Sahrawi representatives are present at the talks due to Moroccan insistence.

1976: Spain announces its official withdrawal from Western Sahara on 26 February. A day later, the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic is declared by the Polisario Front. With support from Algeria and Libya, it fights on against both Morocco and Mauritania, its forces bolstered by refugees.

1979: After three years of attacks by the Polisario Front, which have destabilised the country, Mauritania is forced to withdraw and renounces its claim on the region on 5 August. It recognises the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic. Morocco takes much of the territory previously controlled by Mauritania.

1980 onwards: Sporadic fighting continues between Morocco and Polisario. A giant sand wall is built between Western Sahara and southwest Morocco to deter attacks by Sahrawis. “The berm” will eventually extend 2,700km and take seven years to complete.

1991: Ceasefire declared on 6 September under the peacekeeping mission United Nations Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara (MINURSO). Its purpose is to monitor the cessation of fighting, including the movement of troops on both sides; repatriate prisoners and refugees; and conduct a referendum in 1992. The UN recognises Western Sahara as a "non-self-governing territory".

1992: No referendum takes place, amid a dispute as to who can vote.

1997: The Houston Agreement, coordinated by James Baker, UN representative and former US secretary of state, fails to restart plans for a referendum.

2003: The UN-sponsored Baker Plan, intended to replace the Settlement Plan, stalls amid Moroccan opposition to any referendum.

2020

13 November: The Polisario Front says on 13 November that the ceasefire has come to an end after Morocco resumed military operations in a buffer zone.

10 December: The US recognises Morocco's sovereignty over Western Sahara in return for a Morocco-Israel normalisation deal.

Malfoth Hmed, a 30-year-old drummer in Polisario’s army, fought in the skirmishes in the days immediately following the flare-up at the southern Gueguerat border post that began the current round of hostilities. “I was proud that the war began, it’s good for all young people,” he tells Middle East Eye.

Armed with Kalashnikovs and mortars, Hmed and a couple of dozen other soldiers would stage attacks on Moroccan bases along the berm, a 2,700km-long fortification mostly made of sand walls that has locked Polisario out from 80 percent of Western Sahara.

“First we would approach the wall and fire our Kalashnikovs to cause distress in the base,” he says. “Then the older soldiers would fire their mortars. We had the passion to storm the base but were told to keep in line. We were promised that a proper assault would come later, but for now mortars cause the most damage.”

“You can see all generations have passion,” Hmed says. “It means all Sahrawis take freedom very seriously.”

Occasional Polisario military bases - medleys of breeze blocks and blankets - can be found at safe distances from the berm and Morocco’s prying eyes and arms. For units plotting an attack of some sort, clandestine camps are set up closer to the target.

In the area around Mehaires, sweeping dunes shielded by craggy ashen hills make the perfect spot. The sand here is spotless, ruffled only by bird, goat and camel prints - and the obligatory tracks of Land Cruisers. “We strike at the wall every few days to keep the Moroccans on alert,” says Bega, the commander. “That constant status tires and depresses them, and that is when we attack a base.”

In preparation, Polisario takes MEE to a ridge a handful of kilometres from the wall, scoping out the target. Through binoculars, the berm is little more than a chalky smear on the hot horizon. “Before 13 November, you could see lots of life on the other side of the wall. Movement between houses,” Bega says. “Now there’s nothing.”

Polisario believes it’s causing “human and material losses”, though when you’re attacking from distance it’s difficult to tell. More than 1,600 “combat operations” have been launched during the past year, the majority in the north in the Mahbes region.

Then there’s the psychological impact on Moroccan troops. According to the Polisario Front, the past year has seen Moroccan courts sentence deserters to three to 10 years in prison over charges of fleeing the battlefield. Some 114 soldiers were tried in October on the same charges, the movement said. The Moroccan foreign ministry repeatedly failed to respond to these allegations when asked by Middle East Eye.

Meet the Polisario veterans

Polisario’s military leaders keep their cards close to their chest. Commanders refuse to divulge how many men are in their units, let alone how many have been killed during the fighting overall. It’s believed to be over a dozen, all apparently buried in the “liberated territories”.

The leadership boasts that Sahrawis are returning from the diaspora in their droves to fight. Good luck finding out how many are actually participating in the conflict.

Many soldiers are in their 60s and 70s: others are far younger. “The youngest solider I have in my unit is 15,” says Salem, the battalion commander. “He is involved in all elements of service.” As for equipment, MEE is told that Polisario’s soldiers have all manner of weapons, “from the Kalashnikov up, up, up”.

At the Mehaires temporary base, 23mm anti-aircraft guns are displayed with swagger, until one breaks down during a training exercise. There are Grad rockets and mortars in Polisario’s possession, too, some Soviet-era tanks and even the odd drone, hobbyist crafts adapted for military matters.

But fresh arms supplies are a distant memory. Algeria, Polisario’s closest ally and patron, has an antagonistic relationship with Morocco, and gives Sahrawi attacks its blessing. It is unlikely, though, that Algiers is providing Polisario with new gear. Other previous weapons deliveries came from Muammar Gaddafi, and he’s dead.

Riccardo Fabiani, analyst at Crisis Group, a conflict-resolution organisation, says: “All the equipment dates back to the late 1980s, early 1990s. They haven't really been able to secure anything else after that. The Algerians are reluctant to really provide them with any more serious types of equipment.”

Morocco, in contrast, has one of the most powerful armies in Africa. Fabiani says: “This is a country that has been investing in their defence facilities, particularly in Western Sahara, for decades. So they have detection equipment and radars and drones and all sorts of facilities all along the sand berm. They can spot a unit from 50-plus kilometres away. They don't need to wait until they get close to the berm.”

Polisario’s fighters point out that they’ve always been outgunned. Despite Moroccan military superiority, the movement scored notable successes in the 1975-91 war, particularly during the early years.

Back then, Sahrawi knowledge of the land was an incalculable asset. Polisario fighters would emerge and disappear at will. That know-how hasn’t evaporated: Sahrawi soldiers still breathlessly charge through the desert at night without lights or roads, guided by the stars above and the stones below. But technology has now outstripped that advantage.

Ali Mohammed is a man with a round face and a square cap who, after years studying in Havana, speaks Spanish with the occasional Cuban flourish. He remembers well the last conflict and, though sanguine, is realistic about the challenges faced in this new millennium.

“I can say that I am honestly quite scared when attacking the Moroccans,” he tells MEE. “I have only this Kalashnikov when I’m shooting at the base, and they have all this new technology. Most frightening of all are the drones”.

Fear of Morocco's drones

Morocco has Turkish- and Chinese-made combat drones, and has been striking an import deal with Israel too. The kingdom insists it uses neither its combat drones nor surveillance craft east of the berm.

But Polisario points to various incidents that it maintains were the work of drone strikes. The first two were in April, 13 days apart but both reportedly near the Erni River in northeastern Western Sahara’s Tifariti region.

In the first alleged strike, Addah al-Bendir, head of the Polisario gendarmerie, was killed. The loss was stinging. “He was one of our very best. In knowledge, experience and technical ability,” Bega says.

Then in August, Polisario accused Morocco of targeting a convoy of civilian trucks with a drone strike. The missile, Bega says, hit the back of one truck. The three passengers escaped out the front.

Today its burnt-out wreck lies in the triangle of territory where Western Sahara meets Algeria and Mauritania, preserved and isolated like the carcass of an elephant that has wandered off to die.

“We found fragments of the missile inside the truck,” Bega says. “Our tests indicate the drone was almost certainly Israeli.” MEE has been unable to verify that claim independently.

More recently, Polisario has accused Morocco of killing Sahrawi and Algerian civilians in drone strikes. Images circulating online suggest UAE-supplied Chinese-made Wing Loong II drones were used.

Fabiani says: “There is by now a lot of circumstantial evidence that Morocco has been using drones against the Polisario in Western Sahara and probably in the attack against Algerian trucks at the beginning of November.”

Yet questions remain over the killing of Bendir. “There were many conflicting theories and interpretations, and it looked like an F-16 had actually been involved in the strike and the drone was just there to identify the convoy.”

On the ground in Western Sahara, drone attacks are a point of pride. MEE asked multiple Polisario fighters and commanders if they had witnessed strikes. Most said they hadn’t. A handful refused to answer.

“The drones patrol here all the time,” says Salem, the battalion commander, who is responsible for the 200km of berm around Mehaires. “I myself have never faced a drone strike - but they exist, they exist, they exist.”

Algerian anger at Morocco

This war, if it can indeed be called a war, is low intensity to say the least. Morocco refuses to even acknowledge the breakdown of the ceasefire.

And as victories against Morocco go, the most significant for Polisario during the past year has been not on the battlefield but in the corridors of power. In September, the European Court of Justice sided with Polisario and ruled an EU-Morocco trade deal illegal.

Yet the fighting has energised Sahrawis young and old. Brahim Ghali, the Polisario president, has suggested negotiations to end the fighting are possible, particularly with the arrival of Staffan de Mistura, the new UN special envoy to the region.

But it could be a hard sell to many Sahrawis.

Salem is 74. He was born in Laayoune, Western Sahara’s biggest city now under Moroccan control, and joined Polisario at 26. As someone who has lived through both war and peace, he’s adamant about which direction the Sahrawis need to take.

“Our land cannot be freed diplomatically. There is no point in negotiating. Thirty years was enough,” he says. “As Sahrawi fighters, the main thing is we have hope. We know if we don’t take our land by force we will never get it.”

The threat of escalation looms, particularly as tensions between Algeria and Morocco risk boiling over. Algeria has been enraged by Morocco’s unilateral moves and diplomatic successes in Western Sahara, where various Arab and African countries have begun setting up consulates. De Mistura’s appointment, Algiers hopes, will increase the chance of a negotiated settlement.

A source in the Algerian foreign ministry told MEE: “The question of Western Sahara is a question of decolonisation, which falls under the UN. Algeria has always defended the inalienable right of the Sahrawis to self-determination and condemned the aggressions by Morocco.”

But ties between Algeria and Morocco are currently at a nadir. In August, Algiers broke off relations, citing Western Sahara and “hostile manoeuvres”. The killing of three Algerians near Bir Lehlou in November only soured things further.

Meanwhile, Mohamed al-Wali Akeik, the Polisario army chief of staff, has threatened to expand operations beyond the berm. Polisario sources said this could include targeting Moroccan infrastructure and industry.

For now, it’s time for the rocket attack. Salem’s troops have waited for the last moments of daylight, and a clutch of twentysomething-year-olds have set up a rocket launcher in a glade of pale acacia trees.

Three times Grads howl through the foliage towards the Smarra section’s Base Nine. Smoke rises in the distance, and the commanders’ eyes widen in excitement. As they flee, faces are turned up at the twilight sky, searching for those elusive combat drones. No sign.

“We rely on freedom-loving people across the world to stand with us,” Salem says. “We are sure people will support us. Our cause is right.”

Soldiers of the Polisario Front launch a rocket against Moroccan forces near Mehaires, Western Sahara in October 2021 (AP/Bernat Armangue)

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].