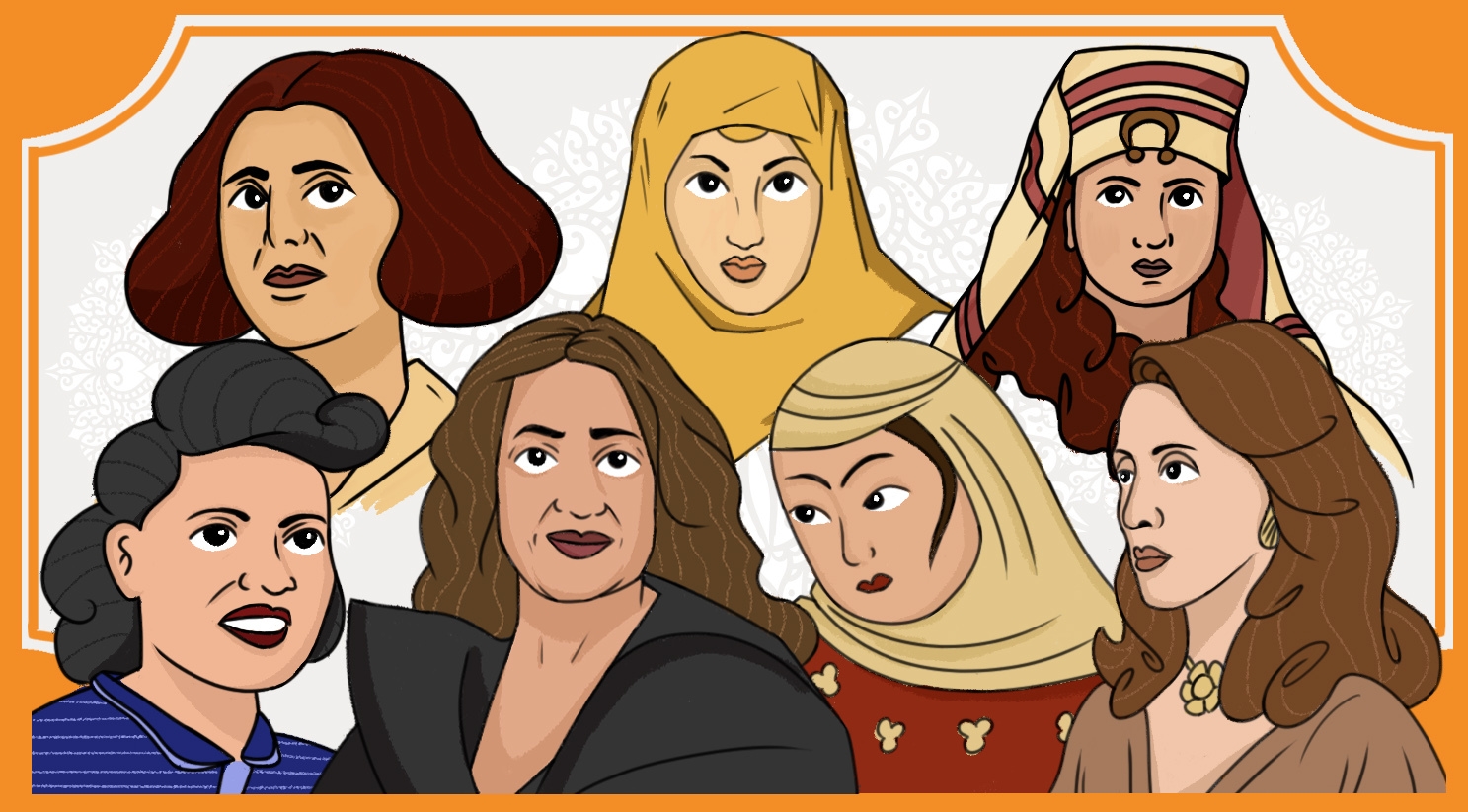

Seven female icons who helped define the Arab world

The role of women in Arab societies has long been a subject of debate and fascination both within the region and outside of it.

On the one hand, gender inequality is widespread and women are poorly represented in governance across the Arab world, as well as in other influential sectors.

On the other, the region has produced women who went on to influence the development of religious thought, the arts and the sciences.

They have been involved in the development of ascetic trends within Islam, founding the first educational establishments in the region and even creating daring new forms of architecture.

Here Middle East Eye profiles seven personalities, who represent a cross section of influential women from the medieval age up until the modern era.

Fatima al-Fihri

Fatima al-Fihri was born in 800 CE in the Tunisian city of al-Qarawiyyin and is credited with establishing the world’s first university in the Moroccan city of Fez.

The University of al-Qarawiyyin was first established as an educational institution in 859 CE, and both Unesco and Guinness World Records have acknowledged it as the world's oldest university.

Al-Fihri was born to a wealthy merchant family who taught her the importance of education and religion.

While little is known about her personal life, it is believed she spent a lot of time as a youth studying Islamic jurispudence, as well as sayings and teachings attributed to the Prophet Muhammad.

When al-Fihri's father died, she inherited his wealth and decided to put it to good use by establishing a madrassa, or school that taught Islamic teachings.

Migrating to nearby Morocco in later life, she decided her new home needed a place where everyone, including women, could study.

Consequently, she established an institution for higher education, which she named after her hometown of al-Qarawiyyin.

The institute was made up of a mosque, library and teaching rooms, and taught Islamic and secular subjects, such as Quranic studies, Arabic grammar, mathematics and music.

Al-Qarawiyyin institute offered diplomas to certify academic attainment, seperating it from other similar places of learning which had been established earlier.

Famous graduates include the Jewish philosopher Maimonedes and the medieval Muslim sociologist Ibn Khaldun.

Sameera Moussa

Born in Egypt's Gharbia governorate in 1917, Moussa went on to become one of the country's most important nuclear scientists.

She first became interested in nuclear technology after the death of her mother from cancer while she was still a child.

Realising the importance of nuclear research in the treatment of disease, she is said to have promised to make: "Nuclear treatment as available and as cheap as Aspirin.”

Moussa excelled at and graduated with a degree in Radiology in 1939, before becoming a researcher specialising in the impact of X-rays on different materials. As little was known about the field at the time, she became one of the world's leading authorities on the topic.

In the aftermath of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki by the US in 1945, Moussa worked to ensure exclusively peaceful use of nuclear technology and organised a conference called Atomic Energy for Peace to lobby governments against the use of atomic weapons.

Her death in a car accident in 1952 was nevertheless shrouded in mystery, with some claiming it was orchestrated by Israel's Mossad intelligence agency to prevent the advancement of Egypt's nuclear research programme.

Zaha Hadid

Born in Baghdad in 1950, Hadid would go on to become one of the most important architects of the modern era, designing structures that are today found in global cities as diverse as London, Baku, New York and Antwerp, among others.

Her designs are notable for their unique and dynamic forms, which incorporate styles inspired by natural phenomena, such as waves and glaciers. Bucking mainstream trends in architecture, her radical designs earned her a reputation as a "deconstructivist".

Made a dame in 2012, the British-Iraqi struggled early on her career in a male-dominated industry. Her earlier designs were considered too "aggressive" and never became more than plans on paper.

Hadid studied mathematics in the American University of Beirut, before studying architecture in London.

In 1979, she established Zaha Hadid Architects and her imaginative, unique designs became world renowned.

In 2004, she was the first woman to be awarded the Pritzker Architecture Prize, and following designed some of the world’s most iconic and striking buildings, such as the London Olympics Aquatic Centre and China’s Guangzhou Opera House.

Hadid also won the Stirling Prize for her work on the Evelyn Grace Academy, a Z-shaped secondary school in London’s Brixton, which features a running track running through the centre of the building.

Another of her notable designs is Abu Dhabi’s Sheikh Zayed Bridge, which features high arches and curves inspired by the rippling of sand dunes.

Hadid died in 2016 at the age of 65, leaving behind 36 unfinished projects, including Qatar's Al Janoub World Cup Stadium and the King Abdullah Petroleum Studies and Research Centre in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Anbara Salam Khalidi

A writer, translator and feminist, Khalidi was the founder of one of the earliest women’s societies in the Middle East, with her influence extending far beyond the borders of Lebanon, where she was born in August 1897.

From a family of Muslim religious scholars and politicians, Khalidi was well read, and became engrossed in reading literature from a young age.

She was soon introduced to feminist thought by a teacher at her school and started writing on the importance of women's education for newspapers in her teens.

During the First World War, Khalidi and a group of like minded women worked in schools and shelters as teachers, and later she travelled to Britain, where she familiarised herself with the suffragette movement and other feminist movements.

According to her memoir, published in Arabic in 1978, Khalidi said she rebelled against the veil at an early age and also refused marriage proposals until she was 30, after which she married Ahmad Samih Khalidi, who was from a well known family in Jerusalem.

In Palestine, she dedicated her time to campaigning and organising for Palestinan civil society, and resisting growing Zionist settlement.

However, along with more than 700,000 Palestinians, the Khalidis were forced to flee Palestine in 1948 during the Nakba. Khalidi died in Beirut in 1986.

Shajarat al-Dur, Sultana of Egypt

A ruler of Egypt with a name meaning "tree of pearls", Shajarat al-Dur was the wife of the first sultan of the Mamluk Bahri dynasty, and the first woman to sit on an Egyptian throne since Cleopatra.

Born in the early 13th century in what is now Turkey, al-Dur is known for being a rare example of a woman reaching the pinnacle of power in the pre-modern Islamic world.

Al-Dur was originally a slave but rose quickly within the palace to become Ayyubid Sultan As-Salih's main concubine and later wife.

When he died, his widow kept his death a secret and took partial control of Egypt's Muslim forces, helping them defeat Crusader armies at the Battle of Mansoura in 1250. The victory thwarted Crusader plans to use Egypt as a base with which to attack and recapture Jerusalem.

With As-Salih's death, there was an expectation for his consort to move aside and cede power to another man, however, al-Dur held on to power first by becoming the Sultana and then by marrying one of her husband's officers, a Turkic Mamluk, called Aybek.

In doing so, Aybek became sultan and the Ayyubid rule in Egypt came to an end with the Mamluks taking their place.

While Aybek took charge of military duties, al-Dur ran the sultanate, but their relationship turned sour when her husband took on a second wife. Al-Dur had Aybek murdered and tried to explain away the murder as a sudden and unexpected passing.

The Mamluk sultan's officers suspected foul play and under torture al-Dur's accomplices admitted the plot. Al-Dur was first imprisoned and later murdered herself.

Rabia al-Adawiyya, Sufi saint

One of the most important figures in the development of Sufism, Rabia al-Adawiyya, sometimes referred to as Rabia Basri, was born into an impoverished family in Basra, Iraq.

Born in the year 701 CE, al-Adawiyaa was sold into slavery, as her family struggled to make ends meet.

Records of her life state that after finishing her household duties, she would spend the entire night in prayer.

According to legend, one day, her master saw a shining light above her head, which illuminated the area around her, some accounts describe it as similar to a halo.

The vision convinced the man to release her on the basis that it would be wrong to keep such a pious woman in his service.

When she became free, Adawiyya dedicated herself to an ascetic lifestyle, rejecting material goods and marriage, and instead dedicating her life to the worship of God.

Her religious views were summarised in her poetry, and she held that belief in God should be based on love instead of fear of punishment or want of reward.

Adawiyya died in her early to mid-80s, and would go on to inspire Sufi thinking for centuries to come.

Fairuz, singer

The voice of Fairuz is ubiquitous around the Middle East and beyond. Her songs evoke feelings of nostalgia, serenity and longing.

Born in Beirut in 1934, Fairouz, born Nuhad al-Haddad, was discovered in her teens by a musician named Mohammed Fleifel. She later acquired the nickname Fairouz, Arabic for turquoise, after her first performance on Radio Lebanon in the late 1940s.

Fairuz's larger than life personality and musical breadth have helped form the archetype of the Arab diva, which artists even today attempt to emulate.

The Lebanese singer grew in popularity, with lyrics extolling the virtues of the Arab nation, of love, and the Palestinian cause.

One of her most well-known songs is Sanarjaou Yawman (We Shall Return One Day), which was dedicated to those forced into exile following the creation of Israel in 1948.

The artist, now 86, is considered an institution across Lebanon and the wider Arab world.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].