Why Biden's 'democracy summit' got it all wrong

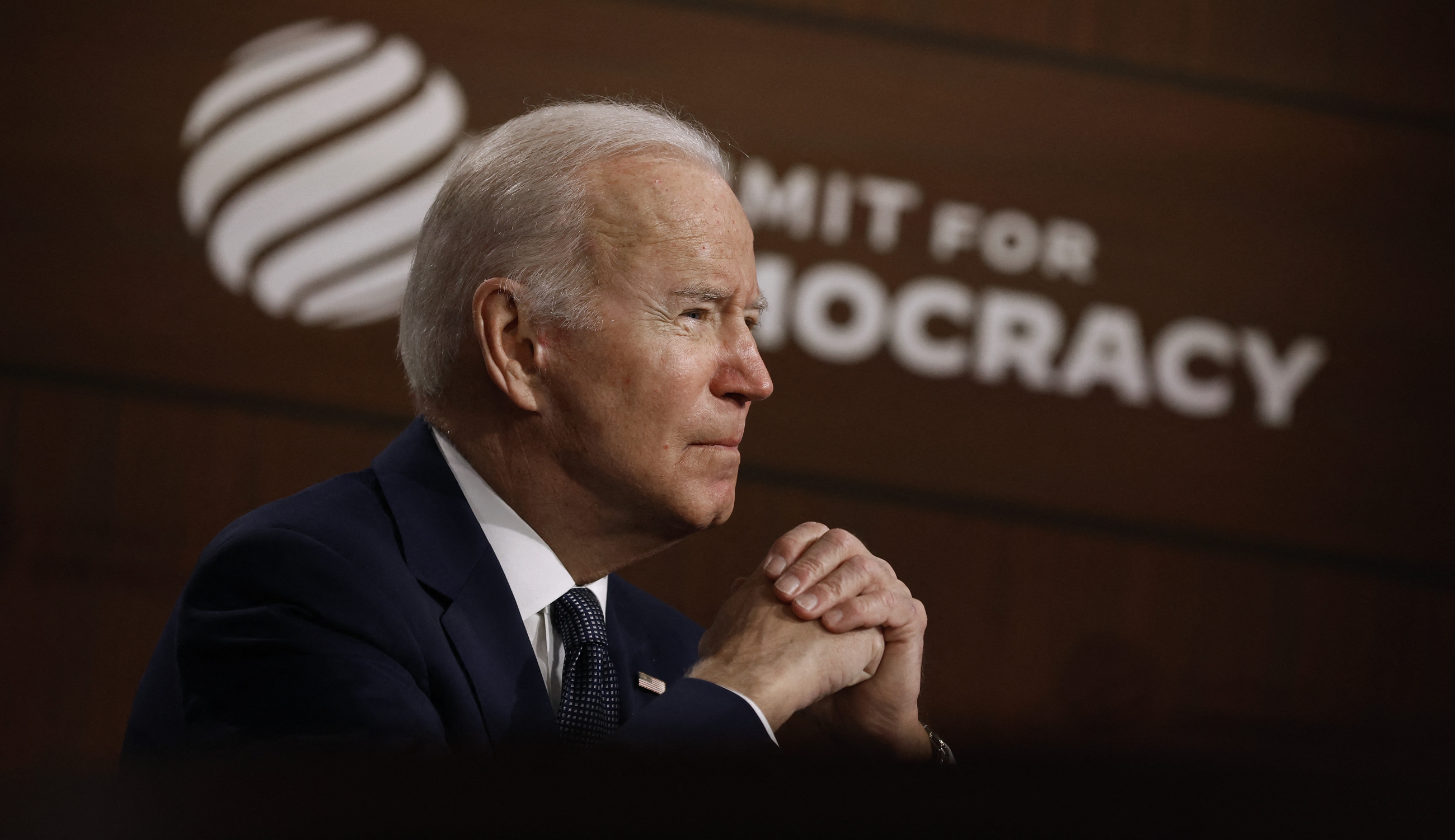

In keeping with his claim that the battle against autocracy is the main geopolitical challenge of the 21st century, US President Joe Biden last Friday chaired a virtual "Summit for Democracy" aimed at defending the West and its satellite states from authoritarianism, fighting corruption, and promoting respect for human rights.

Maybe some great democracy will finally understand that to be credible, it should discard autocratic allies who make embarrassing bedfellows

It is a heartening message, except for two inherently contradictory aims. To fight corruption effectively, tax havens must be tackled, but they flourish among western democracies. As for human rights, maybe some great democracy will finally understand that to be credible, it should discard autocratic allies who make embarrassing bedfellows.

It was a summit for democracy, instead of democracies, an implicit recognition that democracy is a work in progress, that no democracy in the world is perfect and that striving to improve it is necessary. After all, the summit’s main message was that "…renewing democracy in the United States and around the world is essential to meeting the unprecedented challenges of our time."

A confusing guest list

Unfortunately, the summit created confusion with its guest list. Turkey and Hungary (two Nato members) were excluded, while the similarly illiberal Poland, Brazil, Democratic Republic of Congo and Namibia were part of this righteous fest, just to take one example.

As for the Middle East, the inclusion of Israel and Iraq alone on the guest list may have raised a few eyebrows.

The first has a dismaying record in terms of carrying out a trigger-happy security policy in the region, in its daily abuse and humiliation of the occupied Palestinians and even in constraining its own Arab citizens’ freedoms; while the second (Iraq) is still very far from being a working democracy.

The ever-flexible guest list was a figment of US imagination rather than examples of democracy in action.

The decision to invite Taiwan, however, must have added insult to injury in Beijing’s eyes. Chinese President Xi Jinping is probably wondering what Biden exactly meant when, during the three-hour video call the two leaders held on 15 November, he said that the US and China should work for a managed competition. Avoiding provocative actions, apparently, is not part of the toolkit contemplated by Biden’s administration.

For starters, Taiwan is not even a member of the United Nations, nor has formal diplomatic relations with the United States.

As the summit established that protecting and renewing democracy is the core issue, then assessing correctly what threatens it becomes crucial. The US and its close allies have no qualms about it. Democracy is under threat, they argue, by a group of rising and die-hard autocracies with China, Russia and Iran on top of the list.

The summit seemed to be conflating issues here by focusing on an increased US concern about a possible Russian invasion of Ukraine, Chinese military manoeuvres around Taiwan and the nuclear negotiation with Iran. It is not clear if this was deliberate hype to further increase the summit’s momentum or reflected a real fear based on solid evidence.

China, Russia, and Iran are troublesome beyond their borders, but the notion that they are the main threat to democracy is flawed.

A mistaken assumption

Democracy is under threat because of inadequate or just plain bad governance. Its governing elites and economic lobbies have let down too many people for too long.

Crying wolf constantly by pointing at China, Russia, and Iran is a weapon of mass distraction

The enemy is not, for the most part, external. It is internal political and social decay. The dearth of wise leaders is hurting democracy far more than autocrats who can - at best - play the role of spoilers given the right opportunity.

The summit, then, was another good example of a praiseworthy US initiative built upon a largely mistaken assumption.

Over the past few decades there were a number of developments that hurt democracy: tough, and largely ineffective, fiscal adjustment plans dictated by the so-called Washington Consensus; a global financial crisis triggered by Wall Street’s recklessness; the EU’s austerity measures with dire impact on its citizens; an exponential growth of inequality and globalisation that has left too many people behind.

The Covid-19 pandemic was the cherry on the cake as decades of neoliberal policies pushing massive public budget cuts left many health systems completely unprepared for such an emergency. If many democracies continue to perform so badly, many of their citizens might be open to trade some of their freedoms for a more effective government.

Setting a good example

These negative developments ultimately risk boosting the Chinese view that democracy is more about ends than means.

Beijing’s leadership is increasingly and proudly proclaiming its economic performance: according to state-run media, 800 million people lifted from poverty in just a few decades, the great infrastructure it has built, and how effectively it has dealt with the Covid-19 pandemic: all can be compared favourably to Western democracies as a clear sign that its model ensures better governance and does not fail its citizens.

Better and more effective government at home rather than going after autocracies abroad is the best way in which democracy can prevail. Crying wolf constantly by pointing at China, Russia and Iran is a weapon of mass distraction.

The US president is right in claiming that democracy delivers better results than the alternatives, but it must be a functioning democracy and the best way to prove it is by setting good examples.

As it has been authoritatively recalled by a leading American scholar, the US does not seem in a great position right now to preach the virtues of democracy; and there is the serious risk that it could be in a far worse situation in 2024 if the Republicans return to the White House.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].