Arab despots may have won the battle, but the struggle is not yet over

This was the year when a state funeral was held for the Arab Spring. Governments and parliaments that were either dominated or supported by Islamists, and others who gained power through the ballot box, have been thrown out in Tunisia and Morocco.

The last men standing have fallen.

Only one model for the Arab state survived - an absolute ruler, military or royal, it hardly mattered, atop a structure built out of secret police, special forces, and bought journalists

Last summer, when Tunisian President Kais Saied froze parliament, dismissed his prime minister and announced he would rule by decree - in a move his own advisers had dubbed "a constitutional coup'' - Tunisia fell under the same authoritarian shadow it had spent the last decade trying to escape.

Tunisia's Islamists found themselves shunned and alone, treated like a toxic political brand, outside the locked gates of parliament.

Few of Saied's secular opponents were initially prepared to go out onto the streets for them. Sensing the tide of public opinion had turned against them, Rached Ghannouchi, the leader of Ennahda and the Arab Spring's chief intellectual, acknowledged his movement's share in failing to deliver tangible economic benefits.

Everyone then pitched in by writing the Arab Spring's obituary.

The West, which had never stopped conflating political Islam with violent radicals, breathed a collective sigh of relief. Had not the Arab Spring morphed into an Islamist winter, they reminded themselves? Sage looks all round. The Russians saw the Arab Spring as another "colour revolution" hatched by the CIA, like those in the former Yugoslavia, Georgia, and Ukraine had been, and potent enough to break up empires.

The Chinese saw this demise of democracy as justification for their own continued campaign against the Uighurs. The Iranians had a complicated relationship with the Muslim Brotherhood, but they never welcomed the Brotherhood challenging the Islamic Republic's claim to be the sole representative of Islam.

Last, but not least, were the Arab princes themselves.

An Orwellian mixture

Tunisia was the last scalp to be placed in the trophy cabinet displaying the democracies those Arab princes had managed to subvert. It was a triumph for a younger generation of despots, princes whose rule was so Machiavellian it made their fathers and uncles seem like Guardian-reading social workers in comparison.

Henceforth, only one model for the Arab state survived - an absolute ruler, military or royal, it hardly mattered - atop a structure built out of secret police, special forces, and bought journalists.

Their people were governed by a truly Orwellian mixture of mind control and oppression. In their hands, the internet became an instrument of mass surveillance.

The opposition, whether secular or Islamist, rotted in prison, and many of them died there. Those who could not flee would wait to be reported by neighbours. A tweet would be enough to decide your fate. Those who fled would be permanently concerned about the fate of the families, who were in effect hostages.

This was the year when the resurrection of Donald Trump's "favourite" dictator Abdel Fattah el-Sisi of Egypt - "he is a fantastic guy, he took control of Egypt" - continued under Joe Biden.

Biden expressed his "sincere gratitude" to Sisi and his mediation team for playing "such a critical role" in the diplomacy that ended Israel's attack on Gaza last May.

Far from being an international pariah, the Egyptian dictator has become a regional role model. Saied in Tunisia and General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan in Sudan turn to him for advice.

Members of Egyptian military intelligence were in the presidential palace in Carthage when Saied grabbed power. Egypt's intelligence chief, Major General Abbas Kamel, was similarly in Sudan days before al-Burhan's October coup. He reportedly told Burhan that Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok "must go".

Sisi, the chief practitioner of military coups at home, now exports them. And Washington still has his back. On the stump, Biden promised no more blank cheques. In power, he wrote out a few more.

Game over?

So, is it really game over for the revolution that swept the Arab world in 2011? Did all those hopes and intoxicating dreams of freedom and dignity just evaporate into thin air? Was it a brave but ultimately doomed venture?

Irrespective of whether the Brotherhood is dead and buried, the Arab State itself is in headlong, and I would argue, terminal decline

Both sides of Tahrir Square, secular and Islamist, made huge mistakes, each, in turn, placing their faith in an army that betrayed each in turn.

To take just the latest error, Ennahda backed the candidacy of Saied. They could have looked a little deeper into his past history. It's all there.

In Egypt, the experiment lasted a year. Mohamed Morsi was in office but, as we now know, was never really in power. Tunisia's experiment lurched on through one compromise after another for 10 years, but, for much of that time, Ennahda was neither in office nor in power. It was, however, blamed for the mistakes committed by governments it did not oppose. But in the rush to blame the victim for the crime, analysts have missed one glaring point. It stares them in the face.

Irrespective of whether the Brotherhood is dead and buried, the Arab State itself is in headlong and, I would argue, terminal decline.

The plotters of coups far and wide cannot rule their own countries. They simply do not know how. It's not in their DNA. Remember the three demands of the January revolution in Egypt: "bread, freedom, social justice". On each of these counts, Egypt is weaker in 2021 than it was when Sisi staged the military coup against Morsi in 2013.

A weaker Egypt

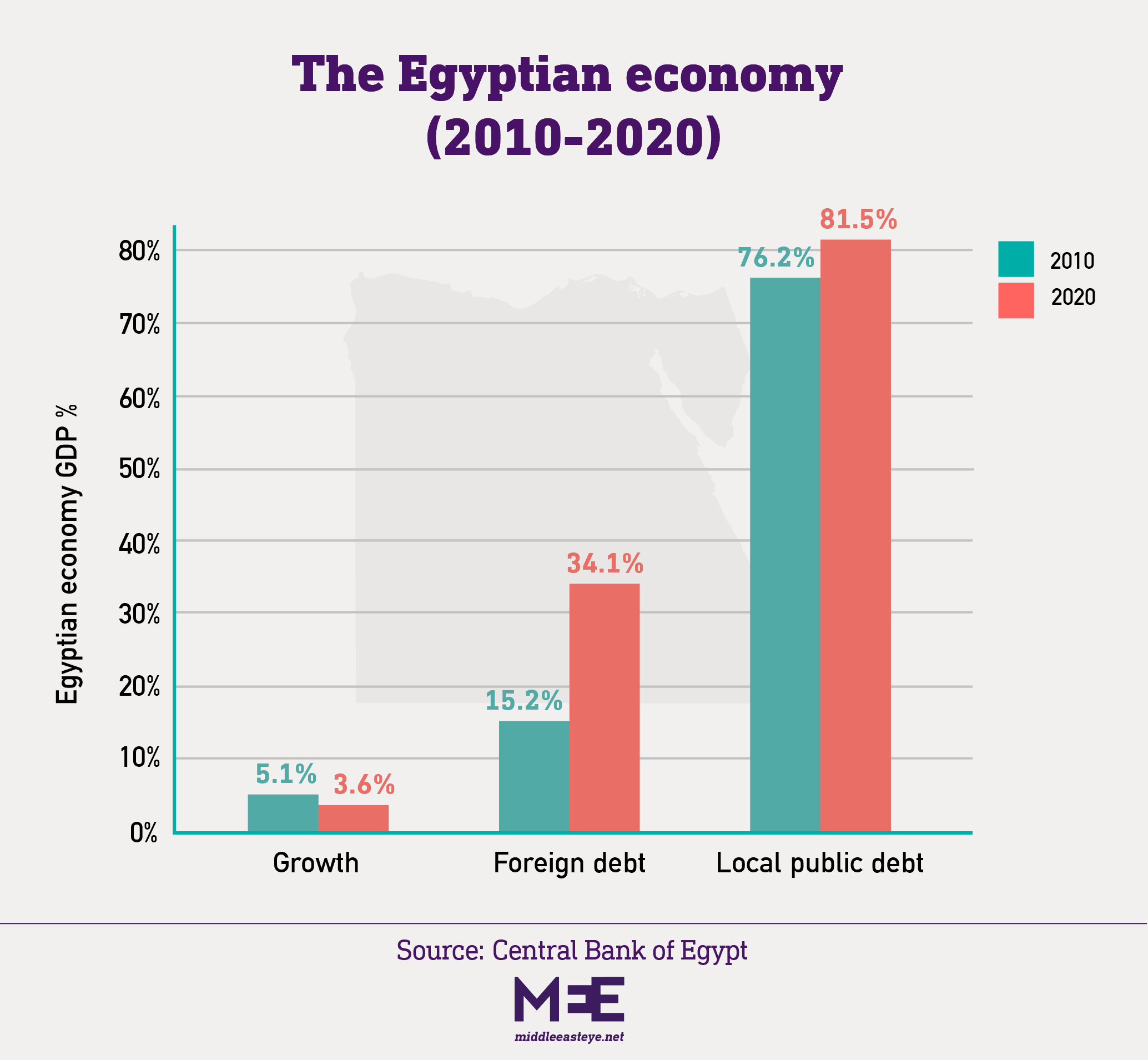

In 2010, growth in GDP was running at over five percent. In 2020 it is 3.6 percent. In 2010, foreign debt accounted for 15.9 percent of GDP. In 2020, it is 34.1 percent. Domestic public debt accounted for 76.2 percent of GDP. In 2020, that figure has risen to 81.5 percent. Foreign debt has gone from $33.7bn in 2010 to $123.5bn in 2020.

All these figures are taken from the Central Bank of Egypt's own records. These figures have only got worse with Covid-19. The current account deficit widened from $11.2bn to $18.4bn in the financial year to June 2021 after tourism plummeted and the trade deficit increased to $42.06bn from $36.47bn.

According to Mamdouh al Wali, an expert on the economy and former chairman of Al Ahram Foundation's board of directors, Egypt is struggling under a mountain of debt. Repaying the interest on foreign and domestic public debt now accounts for 44 percent of the budget, double the figure for salaries, triple the figure for subsidies, and quadruple the percentage for government investments.

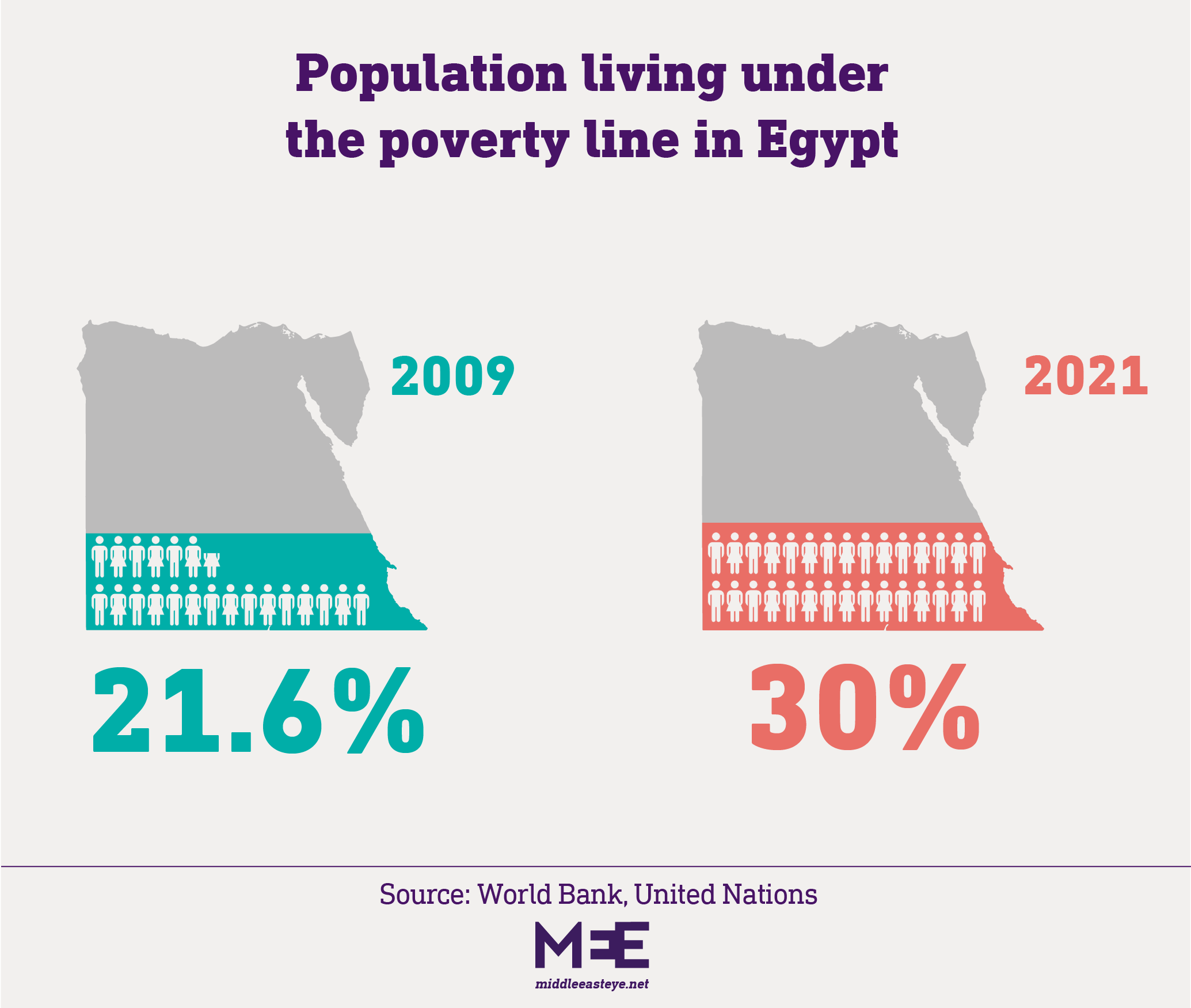

The collapse of Egypt's economy has real effects. No one trusts the official data on poverty rates, which, according to official figures, went up to a peak of 32.5 percent and then reduced slightly to 29.7 percent in 2019/20. But even the latest massaged figure is higher than when Sisi took over in 2014.

In 2009, the United Nations recorded 21.6 percent of the population below the poverty line. In 2021, that rate had gone up to 30 percent, according to the World Bank. This means Sisi has impoverished at least nine million Egyptians.

No wonder that in regions like the governates of Upper Egypt, where poverty is endemic, a boat mafia of traffickers already exists for the perilous journey to Libya and then on to Italy.

"They get on from here [Mansura] to Salum, and then people will take them from the mountain and take them to Benghazi. When they get to Libya, the person will call their representative, who waits until he has around 100, 200 people, then puts them on a boat and sends them to sea. If they make it, they make it, if they don't, they don't," said one parent.

Abdel-Aziz Al Jawhari, uncle of one of the victims, explains how it works. The children, not the mafia, call the parents and ask for money. "The children will call the parents, tell them where they are, say that their friends have already crossed, and ask for 25,000 pounds. If the parents have any belongings, they’re forced to sell them to pay their kids the money."

The Mediterranean coast is now the scene of regular tragedies.

While Sisi spends his money on vanity infrastructure projects of dubious economic benefit, like the extension of the Suez Canal or the Rod El Farag suspension bridge - promoted by a media campaign claiming the accomplishment was the talk of the world - his poorest people are literally dying to escape. All this after tens of billions of dollars has been poured into Egypt's coffers and the army’s pockets by Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Kuwait.

Obscene inequalities

Misrule is regional. The UN's Food and Agriculture Organization calculated that 69 million people were going hungry in 2020 in the MENA region, as a result of multiple social pressures - protracted crises, social unrest, lack of equality, climate change, the economic fallout of the Covid-19 pandemic.

In Iraq, a country brimming with oil and natural resources, 25 percent of the population was poor and 14 percent unemployed. But it has produced one tradable commodity - five million orphans, roughly five percent of the world total.

But life goes on for the Gulf princes in unparalleled luxury.

A court in London ruling on a divorce settlement between Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid al-Maktoum, the ruler of Dubai, and his ex-wife Princess Haya heard how the married couple spent £2m ($2.68m) on strawberries. Their children Jalila, 14, and Zayed, nine, had annual allowances of over $13m each and access to a fleet of aeroplanes including a custom-fit Boeing 747. There were 80 staff just for the children and mother alone.

These obscene inequalities are the stuff that revolutions are made out of.

What's left of Biden's and Europe's Middle East policy would crumble as quickly as the cake Marie Antoinette advised her people to eat if they woke up one bright morning in DC to see on their televisions the head of Sheikh Mohammed dancing on a spike.

The timber that sparked the wild fire of 2011 is even drier 10 years on. The first wave of mass protest that erupted on the streets of cities across the Arab world in 2011 has passed. But its embers are still burning in those streets and in the hearts and memories of millions.

What happened 10 years ago is only the first chapter of a prolonged and mighty struggle. Another one must surely follow.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye Fench edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].