Palestinians drown at sea while escaping death under Gaza's siege

In a small living room, devoid of furniture, Yahya Barbakh, a survivor of a drowning incident off the Turkish coast, sits on a plastic chair with his son on his lap.

To his left, his mother serves coffee and baklava, a traditional Arabic sweet, to guests visiting the humble home in Khan Younes, in the southern Gaza Strip, to congratulate the family on Barbakh's "miraculous survival".

The young man had returned from Turkey a few days earlier after a failed attempt to migrate to Europe in search of a safe place to live and better living conditions.

The boat that carried Barbakh and nine other Palestinians from the Gaza Strip capsized on 5 November as it sailed from the Turkish port city of Bodrum to Greece, killing two people and leaving one missing.

A long, costly journey

"Two months ago, I decided that I had to do something about the miserable life we are living. I had already done all I could. I've worked as a driver, as a barber, and taken every opportunity to work and live, but, at some point, all of this was just not enough for me and my family to live in dignity," Barbakh, a father of two, told Middle East Eye.

'I woke up and saw only one man lying beside me. I started shouting and gesturing with my hands at the coastguards, trying to tell them that there were 10 people on the boat'

- Yahya Barbakh, survivor

"When I first told my family that I was thinking of migrating, my mother disapproved and was afraid that I would die there. But then I managed to convince her."

The 27-year-old said the family had sold his mother's and his wife’s gold and had borrowed money from his sister in preparation for what he had imagined would be the start of a decent life.

To reach Cairo's airport on the first leg of his journey, Barbakh had to pay around $480 for a visa and ticket, and another $500 for tanseeq, or "coordination," a term for the bribes that ease the crossing from Gaza through Rafah into Egypt.

The money is usually collected by mediators, or go-betweens, in Gaza then transferred to Egyptian officers they are in contact with.

The amount of money Barbakh paid for tanseeq is the equivalent to 37 days' work for the average wage earner in Gaza.

Once in Turkey, he was told by traffickers to head to a neighbourhood in Bodrum, where he had to pay them $3,000 through a mediator's office.

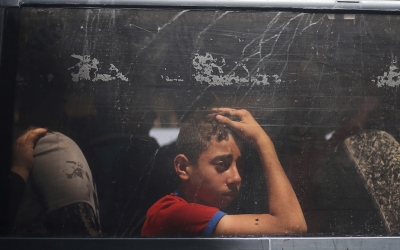

When he arrived in the neighbourhood, Barbakh found dozens of people, including children, from different nationalities, mostly Syrian and Palestinian, waiting for the traffickers to help them migrate.

"They sent us the location through WhatsApp, and we had to walk through forests, so dark that we could not even see our hands, in order to reach the point where they wanted to board us on the boats," he said.

"They had promised us that no more than seven people would be on a safe boat. But when we arrived there on the first day, we were surprised that 30 or 40 migrants and asylum seekers were waiting to board an inflatable boat that had five holes."

According to Barbakh, traffickers usually threaten migrants with calling the police when they refuse to board, and they force them on boats at gunpoint.

Once the boat was full, a trafficker turned on the engine and asked if any of the people on board could drive the boat.

"Driving the boat was not difficult. They just asked us to keep sailing for around 20 kilometres until we reached the other side, the Greek territories," he said.

Barbakh said he and companions had made three failed attempts, the first of which ended with the Turkish police and coastguard arresting them for several days before releasing them. Their last attempt ended in tragedy.

"In the third attempt, we boarded a wooden boat that capsized in the middle of the sea, leaving us fighting off drowning for hours."

‘The fish ate us, mom’

On that fatal day, 14 people, including nine from Khan Younes and one from Rafah, boarded the boat that had the capacity to carry only 10. The traffickers then asked four elderly men and a lady to get off the boat, but the woman refused, insisting on reaching her fiance in Europe.

"Not long after we started sailing, the wind blew the boat and water started streaming in. We panicked and used everything we had to remove the water," Barbakh said.

'This is too much for us to handle, too much pain. He escaped wars and lack of opportunities only to die like this, away from home'

- Um Nasrallah

"Some of us took off our woollen shirts and jackets to soak the water and wring it out back into the sea."

Barbakh helplessly watched two people, including his friend, Nasrallah al-Farra, who had planned for the journey with him, immediately drown after the boat overturned.

"The boat capsized, and two guys got stuck underneath. We were unable to rescue them because everyone was drowning just like them," he said.

"It was too dark, and I was sure I was going to die. My life flashed before my eyes as I was struggling to keep my head above water."

About two-and-a-half hours later, Barbakh passed out, and woke up on a Turkish coastguard ship.

"I woke up and saw only one man lying beside me. I started shouting and gesturing with my hands at the coastguards, trying to tell them that there were 10 people on the boat," he said.

"I only calmed down when I saw them pulling out more people alive from the water. By the end of the day, only seven of us were alive. They pulled out two bodies, and one person remains missing."

While he was waiting for the coastguards to pull out the rest of his companions, Barbakh used the mobile phone of one of the survivors to send his mother voice notes on WhatsApp, which were widely shared on social media.

"We kept drowning for two hours, mom. This is Yahya, mom. Abu Adham [Nasrallah] is gone, Abu Adham drowned. Tell Abdallah," Barbakh said in the recording while crying.

"The fish ate us, mom, the fish ate us."

Intolerable environment

Since Israel's deadly attack on the Gaza Strip in 2014, hundreds of people and families have risked their lives boarding shabby rubber and wooden boats to leave Gaza in search of a better life in Europe.

Two weeks after Israel's military campaign ended, Palestinians woke up to the news of the tragic drowning of more than 400 migrants and asylum seekers in international waters southeast of Malta. Most of the victims were Palestinians from the blockaded enclave.

Since then, the number of migration attempts by sea has risen significantly, with the number of people trying to leave Gaza growing after each military attack on the Strip.

Although Barbakh knew that the journey would not be easy, he did not expect that he would end up in Gaza again.

"I already knew that we were going to experience some difficult circumstances, but I thought that, whatever would happen there, it would be easier than my uncertain life here," he said.

"We don't have any future here. My father is dead, and I have to make a living for myself and my family, including my mother and siblings. I thought that, when I arrived in Europe, I would work in any profession and send my family money."

According to the World Bank, the unemployment rate in Gaza is roughly 50 percent, while more than half of its population live in poverty. Following Israel's military campaign on Gaza in May, 62 percent of Gaza's population are now food insecure.

'I want my children to live'

While Barbakh returned home a few days after he was rescued, two other families were preparing funerals for their sons who had drowned in the incident.

Um Nasrallah, Farra's mother, told MEE that she knew of her son's death only a few days after the incident.

"They told us that he was still alive in the hospital, but two or three days later they said that he had died," the mother of the 42-year-old man said.

"It is was for breadwinning that he had gone. He had a family that he wanted to support."

Nasrallah's father was transferred to the hospital as his heart problems were exacerbated by the news of his son's death.

'They did not just decide to migrate out of the blue or for fun. They had suffered and experienced poverty and hunger for years before they sought a dignified life'

- Kamal Qudaih, relative

"Ever since he heard the news, his health has severely deteriorated, and we are now spending all day with him at the hospital. It's not easy knowing that the son who had travelled to support his and our family will return a dead body," Um Nasrallah said.

"This is too much for us to handle, too much pain. He escaped wars and lack of opportunities only to die like this, away from home."

Anas Abu Rjeila, who was sitting beside Nasrallah when the boat capsized, was also found dead. His body had floated for hours off the Turkish coast before it was retrieved. Anas's cousin, Mahmoud Aburjeila, is still missing.

"The extreme poverty Anas and Mahmoud were living in and the unstable situation in Gaza are what pushed them to seek a better life abroad," Kamal Qudaih, the men's cousin, told MEE.

"Mahmoud was a father of two children. They had both started small projects in an attempt to make a living before choosing to migrate."

Anas bought two iron barrels to sell barbecue chicken, and Mahmoud built a poultry farm, but both projects had failed.

"Mahmoud used to tell me: 'I want my children to live.' He always repeated this sentence whenever he talked about looking for work opportunities."

Since the beginning of 2021, an estimated 1,600 people have died or gone missing in the Mediterranean Sea while trying to migrate or seek asylum in Europe.

"They did not just decide to migrate out of the blue or for fun. They had suffered and experienced poverty and hunger for years before they sought a dignified life," Qudaih said.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].