While crackdowns on Mediterranean traffickers grew in 2021, so did their business

In 2021, more than 120,000 people fleeing conflicts, poverty and repression crossed the Mediterranean to Europe, according to the UNHCR - an increase of 25,000 from the year before. As those numbers have grown, so too have the people-smuggling networks and the crackdowns by authorities.

The dangers of maritime crossings - let alone the journey to the Mediterranean coast in the first place - are well known. Yet departure countries and NGOs working in them have reported a growing people-smuggling industry.

In Libya, one of the leading departure countries for those looking to enter Europe, reports have found that smugglers pack people into unsafe rubber boats and even extort money from families before they can leave.

The operations have become so lucrative that a recent report found that crossing the English Channel has made migrant smugglers tens of millions of euros this year alone.

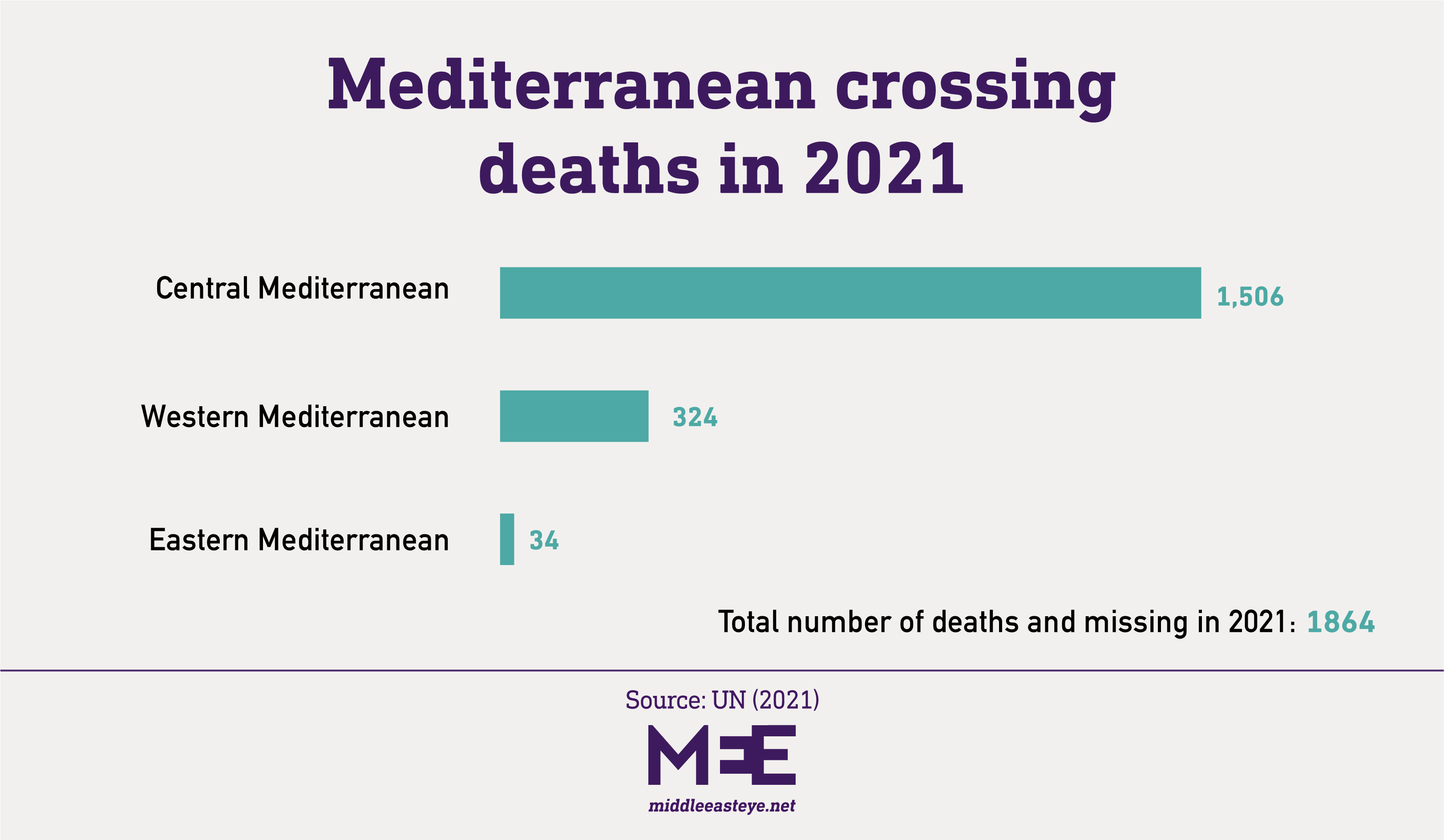

The UNHCR estimates that more than 2,500 people have died or have gone missing at sea this year after attempting to reach Europe. The Internation Organisation for Migration's (IOM) missing migrants project has recorded 23,150 people lost since 2014.

These are estimates, the actual number is likely higher.

According to an annual report by the EU's law enforcement agency Europol, while migrant smuggling networks slowed down during the first wave of the Covid-19 pandemic, they quickly resumed activities.

After entering Spain, Italy, or Greece, smugglers continued to facilitate the journey towards other destination countries, such as France and the UK.

Dr Luigi Achili from the European University Institute, who specialises in migration, told Middle East Eye that the rise of smugglers was a "self-fulfilling prophecy".

In 2015, when one million migrants entered Europe, there were no smugglers, Achili explains. But, "it was in large part created by the implementation of tougher border control measures".

Pushbacks of migrant boats are illegal under European law, yet authorities of several countries are accused of doing them anyway. According to Achili, people trying to cross the Mediterranean develop experience from repeated pushback, and some even become traffickers on that route because of the expertise they've gained.

"What all this means is that the intensification of border control and more restrictive measures, what they do is basically somehow force migrants into smuggling, because you get stranded in a situation of protracting that irregularity," Achili says.

To cope with protracted vulnerability, he says, people turn to smuggling. "You may not, it's not obligatory, it's not mandatory, but you may get into that way to cope with the situation."

In terms of the lucrative nature of the smuggling networks, Achili tells MEE that Western idea of a smuggler kingpin is not necessarily reflected in these networks: operations are conducted by several people in charge of different things, like transport and housing.

"This means that all this multi-billion business doesn't flow into the pocket of smugglers, just a tiny part. Everybody gets something, and they get a slice of the pie. So you won't see smugglers becoming like El-Chapo."

Crackdowns

Though smuggling networks have grown, so have the crackdowns on them.

There are three main routes across the Mediterranean: the eastern, from Turkey to Greece, the central, from Libya or Tunisia to Italy or Malta, and the western, which mostly runs from Morocco to Spain.

Libya has been in turmoil since 2011, with splintered and competing authorities, so little reliable information on efforts to curb networks is available. But it is believed the people involved in the trafficking are also part of the authorities charged with dismantling the networks.

To the west, however, Morocco boasts scores of operations against traffickers.

According to a report by InfoMigrants, Moroccan police have dismantled "150 criminal networks active in organising illegal immigration" since the beginning of the year.

The Directorate General of National Security said since January, it has detained "415 organisers and mediators and 12,231 candidates for illegal immigration".

Security forces also reportedly seized "752 forged travel documents, 67 inflatable boats, and 47 engines and 65 vehicles".

However, the figures only account for police operations, not naval interceptions of migrants heading to Spain.

With Spain only around 20 kilometres from Morocco, the kingdom is a key crossing point. However, crossing the Mediterranean and Atlantic into Spain is very dangerous.

According to the IOM, at least 1,025 people have died this year trying to reach Spain by sea.

Switching routes

To the east, it is a similar story.

At the beginning of the year, the Turkish official Anadolu Agency reported that at least 72 suspected human traffickers in operations based in Istanbul had been arrested.

More recently, after three separate shipwrecks in the Aegean this month, which resulted in at least 31 people dead and more missing, Greek police have reportedly arrested three people on smuggling charges over one of the disasters.

But after a capsized boat was found off the island of Folegandros, after hitting rocks near Antikythera, there are now suspicions that people smugglers may be switching to more dangerous routes in an attempt to avoid Greek patrols.

Meanwhile, traffickers have begun attempting crossings to Italy from Turkey, following the creation of an extended wall at the Turkish-Greek border and increased interceptions, which human rights groups have criticised on the grounds that they often involve alleged illegal pushbacks.

While an official report on smuggling networks in 2021 has not yet been collated, according to an IOM report published last year, 4,282 people smugglers were apprehended by Turkish authorities in various locations inside the country.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].