Turkey is now on an election footing, and the economy could decide it

There is still one and a half years left until the presidential and parliamentary elections in Turkey, due simultaneously in June 2023, according to the law. But the country appears to have already switched to poll mode, as political tensions escalate between the ruling alliance and opposition bloc over the question of when to hold the elections.

Turkey’s election-oriented political atmosphere affects almost every aspect of the country’s decision-making process

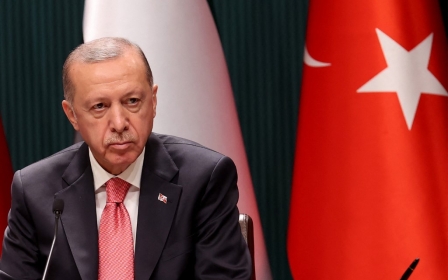

President Recep Tayyip Erdogan held a rally in Siirt, his wife’s homeland in eastern Turkey, last month, while main opposition leader Kemal Kilicdaroglu addressed a gathering in Mersin, a southern province, where a Republican People’s Party (CHP) mayor won the local elections two years ago.

Turkey’s election-oriented political atmosphere affects almost every aspect of the country’s decision-making process - from foreign policy on Libya, Syria, Azerbaijan, Armenia and GCC countries, to domestic issues such as the durability of the newly established presidential system and the government’s efforts to rectify the Turkish lira’s freefall against the US dollar.

The opposition bloc is pushing for early elections, buoyed by opinion poll results which would give them the upper hand if elections were to be held now. The Nation Alliance - which includes the CHP and the Good Party (IP) - is hoping that early elections could give them a fighting chance of defeating Erdogan and his allies after nearly two decades in power. But ultimately, it will be the People’s Alliance, a partnership between the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) and the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP), which controls the Turkish parliament, that will decide on the election dates.

It is unlikely that the government will walk into the elections without strong winds blowing in its favour. The AKP has also made 2023 a big deal, as it's the 100th anniversary of the establishment of the Republic of Turkey.

Before the election year, the AKP has promised that some of its big projects will come to fruition, such as TOGG, Turkey's first domestic production car; Canal Istanbul, a sea-level waterway between the Black Sea and the Sea of Marmara; and other developments in defence technologies.

The ruling party also expects to see some positive results from its new economic programme, which is hotly debated across different sections of Turkish society, as the newly discovered natural gas sources in the Black Sea and the eastern Mediterranean are expected to help Ankara recover from its economic woes.

What’s the opposition agenda?

Opposition leaders accuse Erdogan’s leadership of many failures, but their main target is his presidential system, which they say has created a management crisis in the country. Turkey switched to a presidential system from a parliamentary one following the contentious referendum of 2017.

The new presidential system centralised civilian political power with the president while continuing to keep key powers with parliament. But equally importantly, the new system necessitated political alliances, as it mandated a 50+1 percent vote in order for a candidate to become president. The new system made it almost impossible for a single party to win such a huge mandate.

Subsequently, after the referendum, both the AKP and the main opposition CHP established their own alliances to get the upper hand in the elections.

Despite opposition parties’ furious rejection of the presidential system, it appears to have made the political field more competitive in Turkey. In the previous parliamentary system, the political sphere was under pressure from many powers, such as the bureaucracy, the military and other interest groups with a stake in the capital. Turkish political life has witnessed many interferences from these groups in the past.

But today, with the presidential system, both political successes and failures are attributed directly to politicians. This puts civilians at the centre of political discussions and shows that the government will be held directly responsible for its failures.

The new system also forces political parties with clear differences - from ideology to ethno-cultural issues - to work together in certain alliances, showing how fundamentally the political space of Turkey has transformed.

In this context, besides the alliance of the AKP and MHP, the diverse character of the opposition bloc has revealed an interesting picture. Under the Nation Alliance, the CHP, a centre-left secular party with a strong Kemalist emphasis, has been allied with the nationalist and centre-right Iyi Party, and the Felicity Party, a party that defends some sort of Islamism.

But the Nation Alliance also has some unlikely partners, such as the Peoples' Democratic Party (HDP), a predominantly Kurdish movement with leftist tendencies. During the latest municipality elections, the HDP gave strong support to the Nation Alliance’s candidates in Istanbul and Ankara.

Also, newly established centre-right operations the Future Party and DEVA Party, which broke from the AK Party ranks, appear to support the Nation Alliance.

It shows that for the first time in the republic’s history, seeking a political consensus has become a dominant aspect of the country under the presidential system, even though tensions between the ruling and opposition camps have continued to escalate. As a result, the most decisive factor in the upcoming elections will be the character of political alliances and their ability to forge reconciliation and national consensus.

The empty pot

As with every other country, in Turkey, economic conditions will be a crucial factor in the election. As the late president and prime minister Suleyman Demirel famously said: “There is no government which is able to resist the empty pot.” The pandemic hit Turkey's economy severely, as it has across the globe. Inflation has also recently increased across the world, but its effects have been more negative in Turkey due to decreasing interest rates.

According to the government, the new economic programme, which advocates high exchange rates and low interest rates, aims to turn Turkey into a leading production centre by increasing exports, as commodity prices in the world are rising faster than exchange rates. Moreover, Erdogan pledged to protect his people's money against the dollar, after the lira fell 30 percent against the world's reserve currency on 21 December 2021.

Despite strong criticism of Erdogan’s unorthodox economic policy, recent Turkish export figures appear to support the new approach. Last year, Turkey recorded the highest exports in its history. In November, compared with the same month the previous year, exports increased by 33.44 percent, reaching nearly $21.5bn.

In addition, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has pegged Turkey's 2021 growth rate at nine percent. In the second quarter of 2021, according to Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) data, Turkey became the second fastest-growing nation among OECD members.

Foreign policy

Under Erdogan, Turkey's foreign policy has also changed substantially. While his party initially followed the “zero problems with neighbours” policy, Turkey's relations with its neighbours have deteriorated in the last 10 years, forcing it to deal with various instabilities in Iraq and Syria.

Ankara has also had to deal with Iran's nuclear conflict with the US, as tensions between Azerbaijan, a Turkish ally, and Armenia escalated into war in late 2020. In addition to these developments, the Erdogan administration needs to respond to uncertain developments in Libya, where it supports the UN-backed Tripoli government against eastern military commander Khalifa Haftar.

Tensions with Greece in the eastern Mediterranean over newly found gas reserves and the unresolved Cyprus issue between Athens and Ankara are other problems Turkey continues to face.

Turkey's purchase of the Russian S-400s missile defence system has also created a rift between Ankara and Washington, two Nato allies. Turkey has long been a crucial ally for defending Nato's eastern flank.

Along with these developments, Turkey is reconstructing its relations with GCC countries and Armenia. Most of these foreign policy issues have also increased political differences between the governing alliance and opposition bloc, as Turkey continues to host millions of refugees from Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan.

The opposition bloc, particularly the CHP, promotes the idea that Syrian refugees should be sent back to their country following an agreement with the administration of Bashar al-Assad, which the AKP considers an illegitimate entity.

While other opposition parties like Future and DEVA have different approaches toward the refugee issue, it’s likely to simmer in Turkish society, and will have a crucial impact on the outcome of the elections.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].