As Chile celebrates a left victory, the Arab world’s hopes for change are crushed. Why?

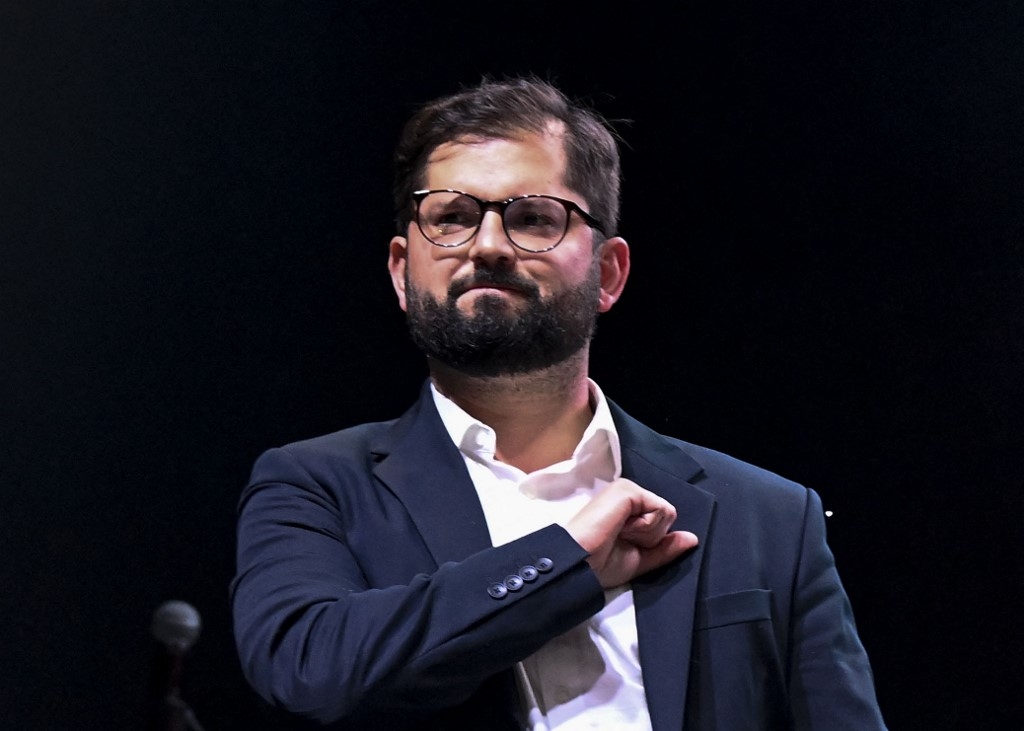

Following a closely fought second round presidential election in Chile, the radical young student leader turned socialist candidate Gabriel Boric won decisively in December, capping a year in which the pink tide swept back across Latin America.

Boric's victory was the culmination of an uprising that began on 25 October 2019, when over 1.2 million people took to the streets of Santiago to protest against social inequality, demanding the resignation of the right-wing billionaire president, Sebastian Pinera.

Boric will preside over a nation that hosts the largest Palestinian community outside the Middle East

One of the talking points of the campaign, and his victory, were Boric’s outspoken remarks on Palestine. He signed a statement of support to the Palestinian cause in a meeting with the president of the Chilean Palestinian community and has backed the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) campaign against Israel’s occupation.

Boric will preside over a nation that hosts the largest Palestinian community outside the Middle East, with between 300,000 and half a million descendants of migrants from pre and post-1948 Palestine.

Historic links

Despite an ocean and many thousands of miles separating Santiago from Jerusalem, the historic links and political parallels between the two regions - the Arab world and Latin America - are worth examining.

Both regions have experienced a period of great social upheaval and waves of uprising and civil violence during the first decades of the 21st century. In Latin America, this process has seen a polarisation between far-right populist leaders such as Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro and Colombia’s Ivan Duque, and a revival of leftist movements in Bolivia, Peru, Honduras and Chile.

While authoritarian and US-backed political forces have sought to destabilise leftist governments across the region, such efforts have largely failed, as seen when the successor to Evo Morales was swept back to power in Bolivia only a year after he was overthrown in a coup.

In Venezuela, US-backed attempts to remove socialist president Nicolas Maduro since 2015, including botched assassination attempts and a blockade of oil sales since 2019, have not achieved their desired goal, leaving Hugo Chavez’s successor securely in power following recent election wins.

The contrast with the Middle East could not be more striking.

The 2010-13 revolutionary wave that shook the region’s authoritarian regimes was met with the brutal force of counter-revolution, leading either to a restoration of the military regime, as seen in Egypt, or a prolonged period of civil war and foreign military intervention, as in Syria and Yemen.

Uprisings from Chile to Algiers

While uprisings swept both regions between 2018 and 2019, the outcome of this popular wave of revolt saw a consolidation of popular-democratic power in Latin America, and its negation in the Middle East.

In the Middle East, hopes were high as mass popular rage against corruption and poverty shook the old older from Beirut to Baghdad.

In Algeria, Sudan, Lebanon and Iraq, the second wave of uprisings to sweep the region scored initial successes against corrupt ruling elites; and yet the forces of oligarchy and counter revolution were able to head off any move toward popular-democratic rule. Tunisia’s democracy fell to an auto-coup by its president, Kais Saied, last July, and Sudan’s future is in the balance, following the October military coup.

A critical question is why? What were the differences between the social movements in each region, the domestic political forces arrayed against them, and the regional and geopolitical factors that intervened to shore up the status quo?

These are not questions that can easily be answered in a column. But some common factors are discernible.

Weak and strong states

The battle against dictatorship and a neoliberal economic order had already achieved some advances in Latin America prior to the recent wave of uprisings.

Despite serious shortcomings, the popular movements that rose up in the late 90s and 2000s had achieved certain victories, first in Venezuela, and later in Bolivia, Nicaragua, and Ecuador. A common element was a link between a mass movement of the poor against neoliberal economic systems, and a demand for greater popular democracy.

The endurance of the post-colonial militarised state, with its access to oil rents and dominance over a weak civil society, has been a huge obstacle to democratic development

The economic crisis and looting of oil rent in Venezuela, and the defeat of the left elsewhere, erased many gains in terms of poverty reduction and hopes for greater democracy.

In the face of coups and judicial seizures of power, as occurred in Brazil, Honduras and Ecuador, popular movements faced defeats and repression, but were not fractured and crushed as they were in the Middle East following the 2011 uprisings.

There are of course big historical differences between the regions. In Latin America, the state is relatively weak as a result of centuries of colonial predation and the resistance to slavery and exploitation by its peoples. In the Arab world, the post-colonial militarised state has endured, with its access to oil rents and dominance over a weak civil society, presenting a huge obstacle to democratic development.

To paraphrase Mirabeau’s description of 18th century Prussia, as one analyst did: “Every state has an army, but in Algeria the army has a state.” Middle East states from the Gulf to North Africa spend huge sums on the military, largely to protect the elite from their own people, and fight proxy wars from Yemen to Libya.

Wars, dictators and sectarianism

The price of resistance and demands for justice are high in both regions. In the Colombian capital Bogota, Senkata in Bolivia, and Santiago in Chile, protests in 2019 were met with bullets and tear gas, just as they were in Basra, Khartoum and Cairo.

Yet from Syria to Iraq to Libya, the extreme violence of foreign-backed intervention, ingrained and pervasive military dictatorship, and violent sectarian movements backed by regional powers, ensured that popular movements were unable to achieve advances around broad goals of social justice and democracy.

The political forces that existed in the region were not conducive to mass democratic involvement, separating the street from political parties. A combination of ideological incoherence within the new protest movements, a pervasive neoliberal orthodoxy among Islamist and liberal secular forces, and the divisions of sectarian politics enabled corrupt regimes to re-establish control across the region.

Even where the peaceful mass movements did not succumb to these divisions, such as in Algeria and Morocco, the old regime was able to re-establish control through a combination of repression, co-option, and a failure of the popular movements to achieve critical mobilisation, combining mass extra-parliamentary street action and organised electoral forces.

Protecting Israel

A decisive factor weighing against the region’s peoples was the role of western and regional powers - led by Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates - in supporting the forces of counter-revolution.

Across the region, thousands of tonnes of US, Israeli, Turkish and Russian-made ordnance, drones and shells rained down during occupations in Iraq and Gaza, wars against the Islamic State, and campaigns against rebel groups, such as the Kurdish PKK and Yemen’s Houthis.

Washington’s geo-strategic focus on the Middle East since the fall of the Soviet Union paradoxically gave Latin America just enough breathing space for its mass popular forces to win key victories

Further, the US has in recent decades invested much more political, financial and military capital in ensuring the security of Israel, primarily by shoring up neighbouring client regimes such as Egypt and Jordan, while giving carte blanche to Israel to suppress internal Palestinian resistance and to destabilise its near enemies in Syria and Lebanon.

While Latin America has suffered a century of US intervention, Washington’s geostrategic focus on the Middle East and Central Asia since the fall of the Soviet Union paradoxically gave Latin America just enough breathing space for its popular and democratic forces to win key victories.

Tragically for the Middle East, it may only be a US refocus on East Asia and China, and its own domestic political paralysis, that gives the region’s long-suffering peoples a chance for democratic renewal in the years ahead.

Chile’s new president referred to the long arc of struggle since the bloody Pinochet coup of 1973, saying: "If Chile was the cradle of neoliberalism, it will also be its grave … Do not be afraid of the youth changing this country.”

Boric's journey from a young student leader of a powerful movement to oppose the privatisation of education in Chile, to stand successfully for president, aged 35, is a remarkable one.

The Arab world too has such figures, from Alaa Abdel Fattah in Egypt, to Marwan Barghouti in Israeli-occupied Palestine, both languishing in prison. Meanwhile, brutal dictators like Abdel Fattah el-Sisi and Bashar al-Assad, or "elected" billionaires such as Lebanon's Najib Mikati, monopolise power.

Forty years ago Latin America was dominated by military dictators, from Santiago to San Salvador. Today it isn’t. The day will come when the peoples of the Middle East will replace the oligarchs with their own Borics. It's a matter of time.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].