More than Cleopatra: Four other women that ruled Egypt

Cleopatra is back in the spotlight after the announcement of a new Hollywood biopic on the legendary Egyptian ruler starring Gal Gadot.

The casting of the Israeli actress in the role has been criticised by many within Egypt, who would prefer an Egyptian actress to play the role instead.

Nevertheless, the movie industry's continued fascination with the "sexy and appealing" queen and her ill-fated romance with the Roman general Mark Antony reveals her central place in the western imagination.

Who was Cleopatra?

Known for her beauty and intellect, Cleopatra was the last Egyptian ruler of the Ptolemaic dynasty and ruled Egypt between 51BC to 30BC.

She was the descendant of Ptolemy I, a Macedonian Greek who took over the eastern part of Alexander the Great's empire, which largely encompassed Egypt, the Levantine coast and southern Anatolia.

Upon her father Ptolemy XII's death, Cleopatra took the throne jointly with her brother Ptolemy XIII, who she also married.

The marriage and blood ties did little to stop the tussle for power between the pair and Ptolemy soon had Cleopatra removed from the throne and exiled.

With support from Julius Caesar, who became her lover and father of her son Caesarion, Cleopatra regained her position as queen and Ptolemy was himself removed from power and killed.

When Caesar died, Cleopatra once again found herself in the midst of another power struggle; this time between Octavian, Caesar's adopted son, and his friend and comrade, Mark Antony, with whom she also started a relationship.

It was a conflict Octavian would win; faced with the prospect of an undignified death at the hands of the Roman ruler, both Cleopatra and Mark Antony took their own lives.

According to one account of her death, the Egyptian queen took her own life by making a poisonous snake bite her on the breast.

Despite her enduring fame, Cleopatra is just one of Egypt's female rulers and others have stories that would compete with hers in terms of intrigue and drama. Here Middle East Eye profiles four others:

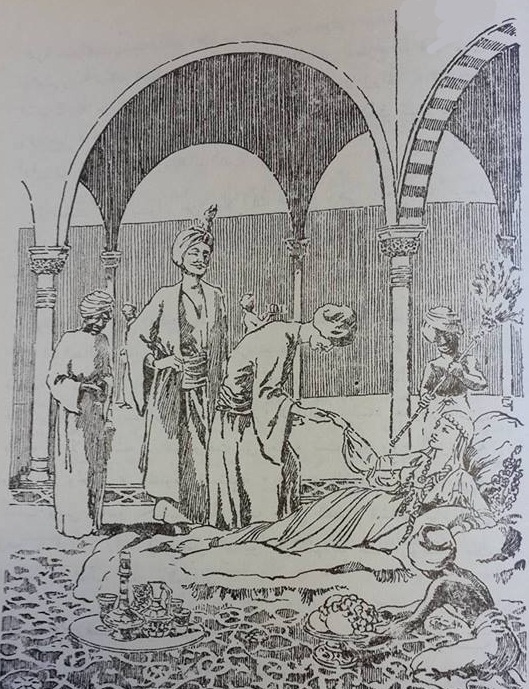

Shajar al-Durr

Under Shajar al-Durr, Egypt transitioned from rule under the Ayyubids, who were descendants of the famed Islamic general Saladin, to the Mamluks, an elite class of slave warriors who hailed from the Caucasus and Central Asia.

Little is known of the queen’s early years - legends say she may have been Circassian, Greek or even Bedouin – but she was most probably born in Armenia around 1220 to a family of nomadic Kipchak Turks.

While her origins are not known for certain, what is known is that she ended up as a concubine within the Ayyubid court.

She is said to have been given her name, which means "tree of pearls", as a reflection of her outstanding beauty.

She became Sultan As-Salih Ayyub’s personal concubine, who is said to have been so besotted with her that he took her on military expeditions with him.

Shajar al-Durr gave birth to As-Salih's son Khalil and the two were soon married, although their child died in infancy.

As her husband’s constant companion, Shajar al-Durr developed a strong understanding of military strategy and politics, knowledge she put to use when the sultan died of illness during a Crusader assault on Egypt.

The European forces had hoped to topple the Sultan’s dynasty, and use Egypt as a springboard to enter Jerusalem, but Shajar al-Durr took charge of the Ayyubid's military forces and successfully fended off the invasion, even capturing one of its key leaders, the French King Louis IX.

While the queen ruled alone for a period of 80 days, there was an expectation on her to take on a male consort, with whom she would share power.

As a result, Shajar al-Durr married the Mamluk officer Aybek, thereby ending the Ayyubid dynasty.

The marriage, however, soured with Aybek's taking of a second wife as part of a political alliance; in a rage, Shajar al-Durr had her new husband murdered, claiming he had died of natural causes.

Aybek's fellow Mamluks eventually extracted confessions from the queen's co-conspirators under torture and had her imprisoned and later killed.

Sitt al-Mulk

Born in Tunisia to Nizar al-Aziz Billah, the fifth Fatimid caliph, and a Melkite Christian mother of Byzantine heritage, Sitt al-Mulk moved to Cairo when the Fatimids shifted their capital to the city in 973 CE.

Her father’s favourite, he is said to have consulted with his daughter for advice on political matters.

When she was aged 26, her father died and her 10-year-old half-brother Al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah ascended to the throne.

The siblings are said to have had a strained relationship with differing views on how to treat non-Muslims and women.

When Al-Hakim mysteriously disappeared, and was later pronounced dead in 1021, his 16-year-old son az-Zahir was declared the new caliph, with al-Mulk as his regent, a position she held for two years until her death.

She is known for her fiscally disciplined administration of the Fatimid empire, as well as liberal and tolerant policies towards non-Muslims.

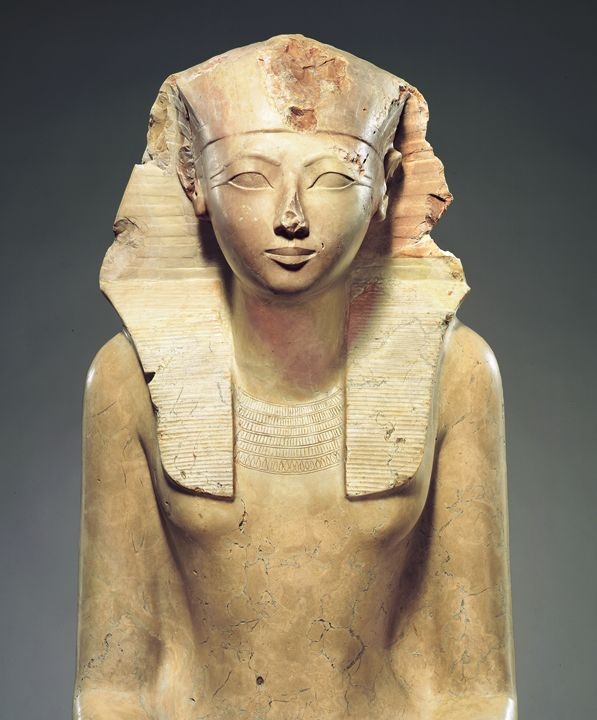

Hatshepsut

Hatshepsut ruled Egypt for just over two decades in the 15th century BCE and was a member of the 18th dynasty.

The daughter of Thutmose I, Hatshepsut married her brother Thutmose II when she was about 12-years-old.

After his death, she became regent to her stepson Thutmose III, who was Thutmose II's son with another woman and therefore also her nephew.

As pharaoh, Hatshepsut worked on building monuments and encouraged the arts; she herself features in a lot of sculptures as an androgynous character, sometimes presented as a male with muscles and a beard.

While leading military expeditions in Nubia during the start of her reign, Hatshepsut's foreign policy was largely focused on trade rather than war.

Under her rule, Egypt imported trees from the Land of Punt (modern-day Somalia). These were used in the production of myrrh, a resin produced from tree sap, which was used in medicine, perfume and as a preservative in Egyptian burial rituals.

Hatshepsut stood down as regent after Thutmose III took full power, and the new ruler set about taking credit for her accomplishments and attempting to remove her name from the historic record.

The former Egyptian queen was buried in one of her commissions, the Temple of Deir el-Bahri, in western Thebes.

Archaeologists and historians only became aware of Hatshepsut's identity and huge contribution to Ancient Egypt in 1822, when they were able to decode and read the hieroglyphics on the walls of Deir el-Bahri.

What is believed to be her mummy is now on display at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

Zenobia

Zenobia was queen of Palmyra, a city in the Syrian desert known for its temple ruins, and lived in the 3rd century CE during Roman domination of the Near East.

Known for her beauty, might and intelligence, she could speak Latin, Greek, Syriac and Egyptian Coptic.

She married King Odaenathus, the ruler of Palmyra, in Syria, when she was 14-years-old and when he died in 267 or 268, she became regent for their son Vaballathus.

Palmyra was located on a bustling trade route, with merchants from China and India and remote parts of the Arabian Peninsula passing through towards Roman lands.

While local rulers in the Near East at the time had limited authority, they were formally loyal to the Roman Empire.

At the time, Rome was dealing with invasions by Germanic tribes in its northern territories and, perhaps motivated by a desire to provide security to the eastern regions, Zenobia set about establishing her own empire.

Within a few years of her husband's death, she had taken control of Egypt, Syria and parts of Anatolia, and declared her independence from Rome.

As a key supplier of grain to the empire, the loss of Egypt was intolerable for Rome and the Emperor Aurelian soon dispatched an army to the east in order to put an end to the revolt and defeat Zenobia's army of tens of thousands of soldiers.

At its height, Zenobia's territory spanned from modern-day Ankara in the north to southern Egypt in the south, and the borders of Libya in the west to northern Iraq in the east.

At the Battle of Immae in 271, Aurelian defeated the rebels and soon encircled Palmyra, capturing Zenobia and Vaballathus, forcing the pair to Rome for a victory procession.

Whether they reached the city is debated among experts, with some saying Zenobia died before reaching Rome and others claiming that she was paraded on its streets.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].