Iraqi Kurdish gas to Turkey? Easier said than done

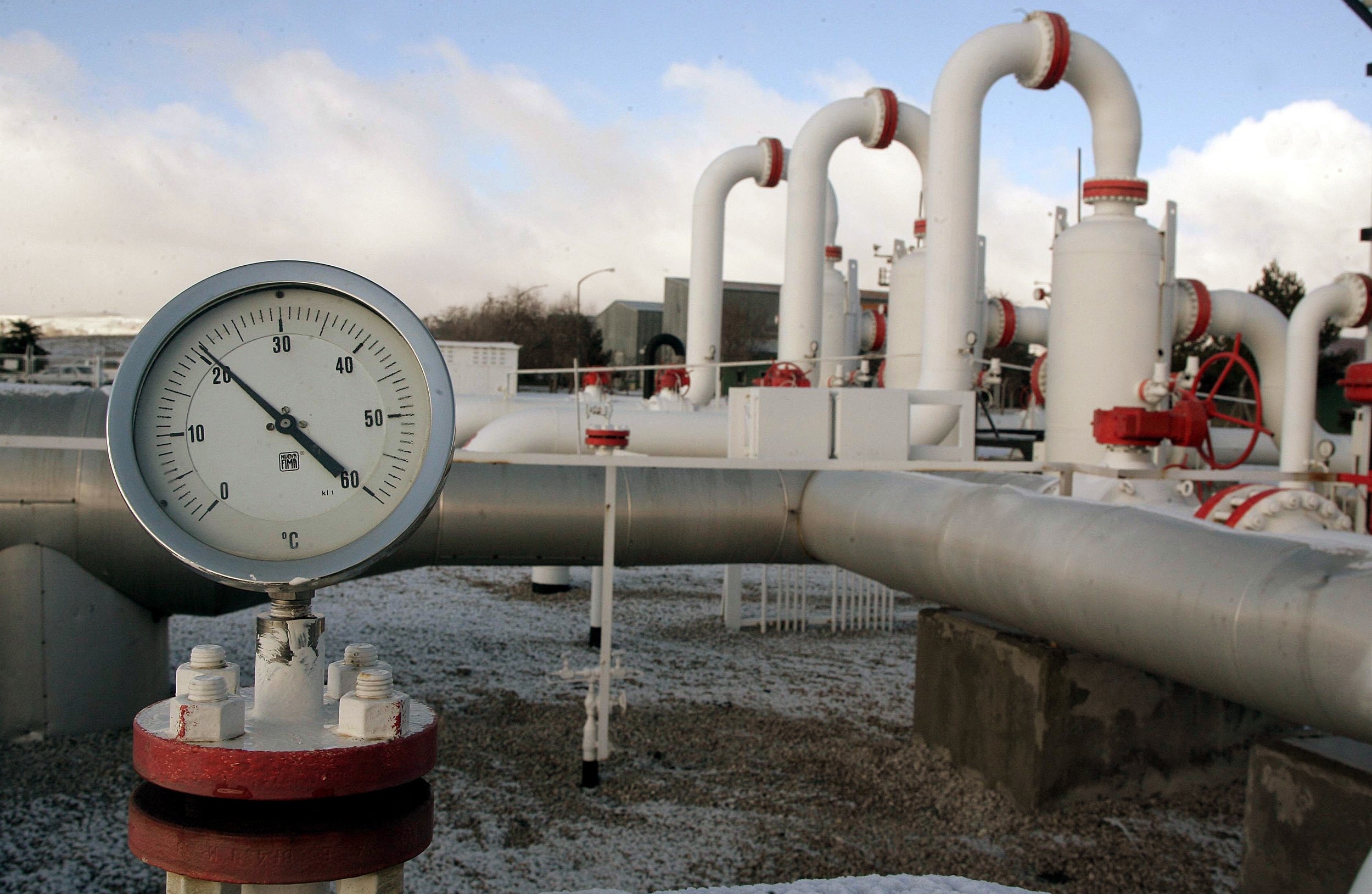

When Iran cut gas supplies to Turkey last month, blaming it on a technical failure in the pipeline, Ankara found itself in a conundrum: either it was going to deny gas to residential areas at a time when harsh winter weather was buffetting the country, or halt supplies to industrial zones.

Eventually, the Turkish government decreased the gas flow to industrial areas by 40 percent, effectively halting production for many companies for 72 hours. Following severe diplomatic protest and pressure, Iran resumed full supplies before the 10-day limit assured by Tehran.

Supplies were back, but questions over Iran's reliability remained.

Many Ankara insiders don't believe the Iranian malfunction excuses, and think Tehran preferred to use the gas for its own domestic consumption.

This is why Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan met Nechirvan Barzani, head of Iraq's semi-autonomous Kurdistan region earlier this month. Erdogan asked his Kurdish counterpart to help import gas from Iraqi Kurdistan's largely untapped reserves, estimated to be 25 trillion cubic feet.

However, the idea is facing many legal and technical hurdles, as an Iraqi Federal Supreme Court judgment this week cancelled a 2007 gas and oil law that granted the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) authority to independently manage its energy sector, including licensing and exports. The ruling also declared all current KRG contracts invalid.

Two senior Turkish officials told Middle East Eye that, even before the court decision, Ankara had intended to discuss the issue with Baghdad first. “We know that this is something we have to talk to the Iraqi government about and get their approval,” the official said. “So the latest court judgment is besides the point. However, its implementation wouldn’t be easy either.”

Iraq and Turkey are already in court over a deal between Ankara and Erbil in 2014, which allowed the latter to pump crude oil to Turkey through the Kirkuk-Ceyhan pipeline. Baghdad sued Ankara in 2015 through the International Court of Arbitration, saying the deal is illegal, seeking $25bn in damages.

The federal Iraqi government and the KRG have been locked in dispute over the latter independently selling oil and gas and taking all its revenue. Though the Supreme Court decision further solidified Baghdad’s legal case against the Turkish-KRG deal, it is believed the Iraqi government isn't particularly interested in pursuing the lawsuit all the way and collecting the damages for now.

One Turkish official said Iraqi Prime Minister Mustafa al-Kadhimi, who is seen close to Ankara, has postponed the arbitration dealings due to improving ties between the two countries. Erdogan’s opposition to an independence referendum held in Iraqi Kurdistan in 2017 brought Baghdad and Ankara closer together.

Political negotiations

Iraq is currently embroiled in tense political negotiations as its parties try and form the next government following October's parliamentary elections. Some believe developments in the courtroom are tied to political competitions being played out elsewhere.

“The timing of this Iraqi court decision isn’t a coincidence,” Sardar Aziz, an expert on Iraq and the KRG, told MEE. “If implemented, it will change the oil and gas dealings in the country but will also affect the government negotiations. The decision isn't constitutional at all.”

'It is definitely remarkable to see that the court is issuing these judgments one after another that are seen as politically motivated'

- Turkish official

Shia political forces close to Iran have emerged as the greatest losers in October's election.

The KDP, the most powerful party in the KRG, has been in talks with the Sairoun alliance of influential Shia cleric Muqtada al-Sadr - which won the highest number of seats - over forming what Sadr has called a "national majority government". The proposed alliance, which has also seen discussions with Sunni political parties, would exclude other Shia parties that are close to Tehran, prompting an angry response.

Amid these developments, Iraq's Federal Supreme Court has been called on to adjudicate on various petitions, including on the 2007 Ankara-Erbil deal. Some have accused it of being forced into making politically swayed judgements, like nixing the candidacy of the KDP and Sairoon Alliance's preferred choice as president.

The court, however, insists it is completely independent. Regardless, suspicion has arisen in Ankara.

“It is definitely remarkable to see that the court is issuing these judgments one after another that are seen as politically motivated,” the Turkish official told MEE. “Some believe these decisions are all about Iraq’s eastern neighbour.”

Plans afoot

Despite the legal challenges, the KRG is working on plans to bring Iraqi Kurdistan's gas to Turkey. The Erbil-based government last week struck a deal with Kar Group to build a new gas pipeline from Sulaymaniyah to first Erbil and then to Dohuk in the next 16 months for local electricity production.

The pipeline would also bring the infrastructure within 35km of the Turkish border, opening the way for future export plans.

Gokhan Yardim, a former director-general for the Turkish state-owned crude oil and natural gas pipelines and trading company Botas, said Iraqi Kurdish gas was a huge opportunity to resolve Turkey’s growing energy needs.

“Botas has already built a gas pipeline to the Iraqi border, Turkish infrastructure is ready,” Yardim told MEE. “The other side of the border is smooth. It wouldn’t take much time to build a pipeline.”

The KRG is currently using approximately 440 million cubic feet of gas per day from the Khor Mor and Chemchemal fields to generate electricity. UAE-based Dana Gas said last year that it plans to increase production by 60 percent and reach 630 million cubic feet per day in 2023.

“The current output isn’t enough for Turkey,” Ali Arif Akturk, a veteran energy consultant, told MEE. “Work is needed in other gas fields such as Miran and Bina Bawi, which contain sour gas, which has a high hydrogen sulfide level, which is poisonous.”

KRG officials believe at least $4-5bn is needed to start production in those fields and sweeten the gas.

Genel Energy, a Turkish-British company, has already spent around $1.4bn on Miran and Bina Bawi gas fields, including their acquisition, maintenance, drilling and other costs. However, the KRG last year terminated the contracts, triggering a Genel Energy court case against the decision.

Another Turkish company, Cengiz Energy, is also interested in the fields. Cengiz, which is seen close to the Turkish government, reportedly made an application to obtain a licence in 2020 to import Iraqi Kurdistan gas to Turkey. A Turkish official with direct knowledge on the matter told MEE that the authorities were still deliberating on the application and no final decision had been issued.

Akturk, the energy consultant, says Cengiz has a distinct advantage for these two gas fields because of its expertise on sweetening gas.

“They already have some experience in metal reclamation,” he said. “However it will take four to five years to build a new petrochemistry factory. But it is also possible to make additional money from sulfide.”

One KRG parliamentarian said last week that exports to Turkey could begin as early as 2025, which experts find brazenly optimistic.

One of them, Aziz, said Iraqi Kurdistan gas cannot immediately be an alternative to Iran but could nonetheless diversify Turkey’s energy imports.

Turkey in recent years cut its heavy reliance on Iranian and Russian gas by establishing several new pipelines, including for Azerbaijani gas and LNG imports. Ankara also plans to annually produce 20 billion cubic metres from the recently discovered Black Sea gas fields beginning in 2023.

However, Ankara will still need to import gas.

Akturk said despite the huge costs to begin importing Iraqi Kurdistan gas, it will still be relatively cheaper than that from Iran, whose contract with Turkey will expire in 2028. “It has great potential,” he added.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].