Russia-Ukraine war: Why Turkey isn't likely to close the Bosphorus

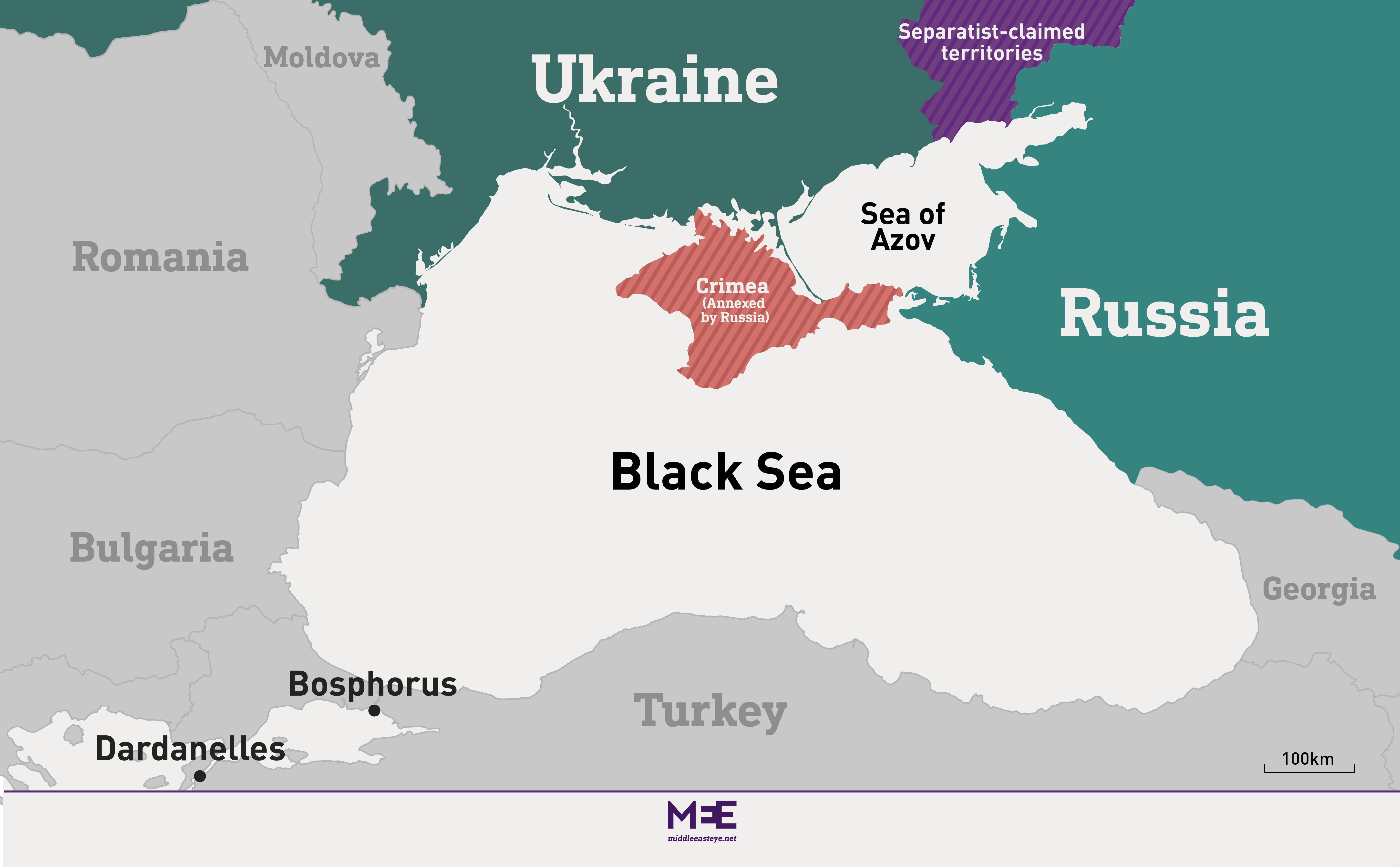

Soon after Russian troops began attacking Ukraine, Kyiv asked Turkey to close its waterways and airspace to Russia, something you shouldn't expect to see happening anytime soon.

There are a raft of legal and political reasons why Turkey is highly unlikely to respond to the Russian invasion by closing the Bosphorus and Dardanelles waterway that provides access to the Black Sea.

Ankara has complete sovereignty over the straits. Yet it is a party to a legally binding international treaty, the Montreux Convention, that regulates its decision to deny access to the crucial waterways.

Omer Celik, spokesperson for Turkey's ruling AKP, appeared to downplay suggestions that the Russians could be cut off. "Turkey will use its power over the issues that could escalate the situation to establish peace. Every application by different states is judged by their merits and criteria," he said about the Ukrainian request.

The Montreux Convention, which was signed by Turkey, the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union and six other states in 1936, clearly allows warships belonging to the Black Sea countries to sail through the straits without any intervention. The convention only limits the timing and the size of the ships.

“Article 19 of the convention is quite clear,” Mesut Akgun, a professor on international relations at the Istanbul Culture University, told Middle East Eye. “If Turkey isn’t a belligerent, it has to allow passage to the warships.”

The Ukrainian government alleges that the same article also gives Turkey the power to close the straits.

Though the article indeed allows warships to pass, even during wartime, it also denies access to battleships belonging to belligerent states. This is open to interpretation but is largely understood as warships that are actually engaged in combat. The article also adds that vessels of war belonging to belligerent powers, whether they are Black Sea powers or not, which have become separated from their bases, may return thereto.

However, the convention’s Article 20 says if Turkey is itself a belligerent, it is up to Ankara to decide whether to keep the straits open for warships. Article 21 also says that if Turkey considers itself threatened with imminent danger of war, it can close the straits.

“I don’t think Turkey will close the straits based on threats of imminent war against itself,” Akgun said. “Since there is no such thing.”

Several western officials, speaking on condition of anonymity, agree that Turkey will need to keep the straits open for warships.

“Otherwise it would be against the convention,” one official said. “And everyone knows that Russia had already sailed its ships through the straits before launching this invasion.”

Turkish officials, on the other hand, underline that Turkey only won the rights granted under the Montreux Convention after many years of struggle, securing the territories involved after the Turkish War of Independence in the 1920s.

One source close to the Turkish government said Ankara wouldn’t want to risk the status of the convention with a decision that would anger Russia.

“At the end of the day, Ankara could say things that could give itself powers under the convention to close the straits,” the source told MEE.

“Yet it would also harm its future standing. You don’t want to provoke Russians for just symbolic gains. It won’t have much impact on the invasion anyway."

Stalin's gambit

Russia hasn't always been happy with the convention's provisions.

After defeating Nazi Germany, the Soviet Union asked Turkey to allow it to establish naval and army bases along the straits, arguing that Turkish forces could not secure them alone. Moscow also requested Turkey hand over its three most eastern provinces.

Instead, Turkey gained US backing and eventually became a member of the Nato alliance.

Russian pressure remains, however. Moscow's demands persisted for years, and Sovier leader Joseph Stalin even personally pressured then-Turkish president Ismet Inonu to at least allow the Soviet Union to establish a military base in the Aegean Sea near the Greek border.

“Turkey won’t risk the convention,” Akgun said. “And that’s about it.”

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].