Who are the Crimean Tatars? The Turkic Muslim minority loyal to Ukraine

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has sparked what is likely to become one of Europe’s most complex conflicts pitting two multi-ethnic countries against one another.

Russian President Vladimir Putin has been keen to highlight the presence of neo-Nazis within the Ukrainian military in his purported quest to “de-Nazify” his western neighbour.

To back this assertion, his supporters have pointed to images, such as a video of far-right Azov battalion members, greasing their bullets with pig fat in preparation for battle with Muslim Chechen soldiers in the Russian army.

While the presence of far-right sympathisers in Ukrainian ranks is firmly established, characterising the entire Ukrainian military and those resisting the Russian offensive as “Nazis” is not grounded in reality.

Besides the fact that Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelensky is Jewish, such accusations are also belied by images of men in Ukrainian army uniform holding up their hands in Islamic prayer.

Muslim volunteers from Chechnya and former Soviet republics are known to have fought against Russian forces in Ukraine since the start of hostilities in 2014. Fighting alongside them are members of a small indigenous minority of Ukrainian Muslims, known as Crimean Tatars.

Who are the Crimean Tatars?

As the name suggests, Crimean Tatars are native to the Crimea region of Ukraine, which was unilaterally annexed by Russia in a 2014 invasion.

With roots in the region going back to at least the 13th century, they are a Sunni Muslim ethnic group who speak a language descended from the Kipchak branch of the Turkic language family, meaning it is a close relative of the Tatar dialects spoken in Russia and more distantly related to the Turkish spoken in Turkey.

The community has a complex history but, like related Tatar groups, their ethnogenesis begins with the spread of the Mongol Empire in the early 13th century.

In 1241, Genghis Khan’s grandson, Batu Khan, conquered the region establishing Mongol rule but in the following decades the huge empire, which covered a region from Eastern Europe to the Korean peninsula, began to fragment.

The western portion was ruled by a confederation of Turkic and Mongol tribes, which came to be known as the Golden Horde.

These new overlords began inter-marrying with native populations in both Russia and Ukraine and adopted Turkic dialects, as well as Islam, as a religion. The Ozbek Han Mosque in Staryi Krym, the oldest mosque in Crimea, was built in 1314.

As the Golden Horde itself fragmented, Crimean Tatars founded their own independent Khanate in the late 15th century.

However, with both the Russian and Ottoman Empires expanding on either side of the Black Sea, Crimea’s Tatars struggled to assert their independence amid imperial jockeying by the rival powers.

The Treaty of Kucuk Kaynarca between the Russian and Ottoman empires in 1774 was aimed at ensuring the Khanate’s independence but was violated by the Russians in 1783, resulting in the annexation of the territory into Imperial Russia.

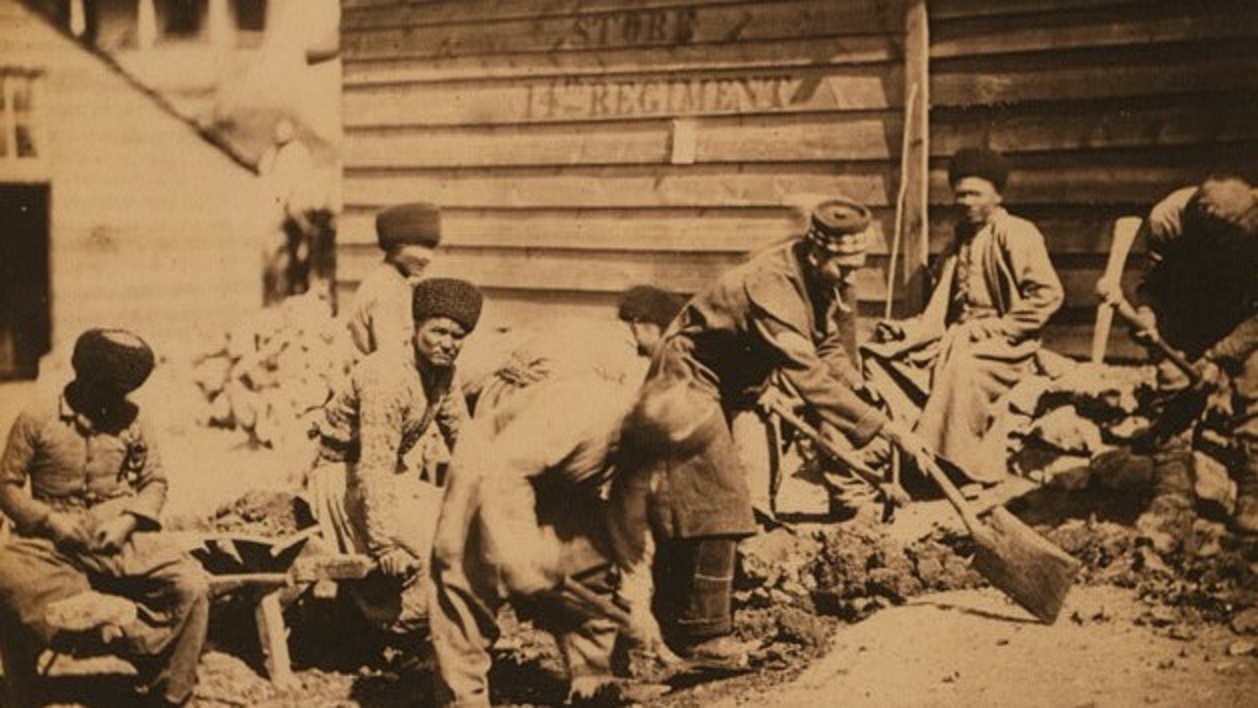

In the decades that followed, discriminatory policies forced tens of thousands of Crimean Tatars into neighbouring states, including the Ottoman Empire.

Crimean Tatars under the Soviets

The community’s modern history has been no less easy, having experienced mass deportation and instability.

Man-made famines in the 1930s due to Soviet collectivisation efforts reduced the Crimean Tatar population, and in May 1944, immediately after reclaiming Crimea from Axis powers, Stalin accused the entire group of collaborating with Nazi Germany. As a result, he forced them into exile to Soviet Uzbekistan as a form of collective punishment.

Aleksandr Nekrich, the late Harvard lecturer on Soviet history, smuggled a book-length manuscript on the deportations, and one woman’s recollection was recorded in a Human Rights Watch report from 1991.

“At 3:00 in the morning, when the children were fast asleep, the soldiers came in and demanded that we gather ourselves together and leave in five minutes.

“We were not allowed to take any food or other things with us. We were treated so rudely that we thought we were going to be taken out and shot.”

In the following weeks, the woman’s family were forcibly resettled in Xatirchi in central Uzbekistan.

The same report states that almost all Crimean Tatars were deported to Uzbekistan, including former Soviet army personnel. Local officials with government vehicles were allowed to drive to rail stations before being made to abandon their cars and join fellow Crimean Tatars on overpacked trains heading eastwards.

Even after Stalin’s death in 1953, tens of thousands of Crimean Tatars remained in Central Asia for decades after the deportations and a sizeable community still lives in Uzbekistan.

Russian annexation of Crimea

Change came about under Gorbachev’s Perestroika period in the late 1980s when the population was allowed to return to its homeland. In 1989, the Supreme Council of Crimea, the region’s former legislative body, declared that the initial forced removals were illegal.

A Ukrainian census in 2001 recorded just under a quarter of a million Crimean Tatars, almost all of whom lived in Crimea. Despite their long history on the peninsula, their numbers amounted to just 10 percent of the total population of the region.

Many of the descendants of those forcibly deported returned to Crimea, becoming leaders in the local community, including Refat Chubarov, who was chair of the Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar People, a representative body recognised by the Ukrainian parliament.

However, the body was outlawed by Russia in 2016, two years after its annexation of Crimea, on the pretext that the group was promoting extremism and ethnic nationalism.

Moscow justified the annexation in 2014 on the basis that ethnic Russians formed the overwhelming majority of the population. The peninsula also has strategic importance for the Russians as the home of its Black Sea fleet at Sevastopol.

Since the takeover, which remains unrecognised among a majority of countries, Crimean Tatars have complained of efforts to silence their community. The historic memory of Soviet and Imperial Russian persecution has meant most prefer Ukrainian rule over the Kremlin’s.

A Russian-organised referendum on the status of the community was subject to boycott calls by both the region’s Crimean Tatar and Ukrainian minorities. Several Crimean Tatars who voiced concerns about Moscow’s takeover have disappeared under Russian rule.

Putin’s top official in Crimea, Sergey Aksyonov, has said: "Crimea returned to Russia forever. Anyone who advocates resistance is advocating bloodshed; of course we can't accept that and will react.”

The fear of further persecution has led to a slow exodus of Crimean Tatars from the traditional homeland with many moving to other areas of Ukraine or to Turkey, which has traditionally provided sanctuary to Muslims fleeing persecution in areas of Russian influence.

They include Ukraine’s 2016 Eurovision winner Jamala, who fled to Turkey. Her winning song was about her grandmother’s forced deportation in 1944.

Others have vowed to stay, either in Crimea or in the Ukrainian mainland, with some taking up arms against the Russians both after the 2014 invasion and again in 2022.

With Ukraine itself now under the threat of Russian occupation, the Crimean Tatars find themselves attempting to throw off the yoke of Moscow’s influence.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].