Russia-Ukraine war: Can Moscow break its international isolation?

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has triggered an abrupt rupture in relations between Russia and the West, with a wide range of ties – from flights to banking and media – severed. The country looks increasingly isolated within the international arena, with even traditional allies such as Kazakhstan remaining silent.

Putin's Kremlin has demonstrated an increased willingness, and ability, to use the military lever to achieve broader strategic and foreign policy goals

How did we get here? And what are the implications for Russian foreign policy moving forwards?

There have been significant changes in wider Russian foreign and security policy since 2000, as the country has recovered from the chaos of the 1990s and developed a more coherent, coordinated policy, perceived by many to be more assertive.

Vladimir Putin has presided over Russia’s return to the international stage as a strong state capable of exerting global influence.

The 2016 Foreign Policy Concept (FPC) made it clear that the Kremlin considers Russia to be a major power within the international system, one that is seeking to consolidate its position as a "centre of influence in today’s world".

Since Putin came to power in 2000, the Kremlin has demonstrated an increased willingness, and ability, to use the military lever to achieve broader strategic and foreign policy goals.

The 'centre of influence'

Russia’s proactive (often ambiguous) use of force across the post-Soviet space (Georgia in 2008 and Ukraine since 2014) and further afield has been related to a variety of issues, not least an attempt to counter the attraction of the EU, Nato and the West, by coercion and threats.

Russia had become increasingly concerned about the perceived expansion of western influence across the post-Soviet space and, in an attempt to counterbalance this, the Kremlin has sought to reassert its primacy by employing an array of economic and military instruments of power that allow it to coerce its neighbours.

In the wake of the 2020 Nagorno Karabakh war and the failed attempted coup in Kazakhstan in 2021, Russia appeared to strengthen its position within the post-Soviet area, facilitated by the apparent disinterest of Western states and organisations, which have been distracted by issues such as the rise in populism and the Covid-19 pandemic.

At the heart of the conflict between Russia and the West are fundamental differences over notions of power, security and international order. Russia’s sense of derzhavnost, its belief that the country is destined to always be a great power (derzhava) based on factors such as its history and territorial size, has been a consistent feature of Russian foreign policy since the disintegration of the USSR.

Russia's 'derzhavnost'

Russia’s belief that it is a great power, with the right to spheres of influence and an indispensable role in global affairs, has led to it asserting its dominance across the post-Soviet space and seeking to expand its global influence. This contrasts starkly with the western emphasis on values, cooperation and partnership.

Over the past decade, Russia has demonstrated a capacity and willingness to project its power and influence around the world, including the Middle East and North Africa, in sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America and Southeast Asia. Russian interests in these areas have traditionally been economic, especially in the arms trade, energy and strategic cooperation.

One of the drivers for its increased foreign policy activism was the search for new "client states" in markets not covered by sanctions imposed by the EU and US since 2014 in response to Russian support for separatists in Ukraine. Russia is the world’s second-biggest exporter of arms after the US, and the defence industry helps bring in a significant amount of foreign currency.

This is likely to continue apace, as Moscow seeks to consolidate existing economic ties and develop new ones. Moscow will continue to exploit any opportunity to further its interests, both political and economic, around the globe.

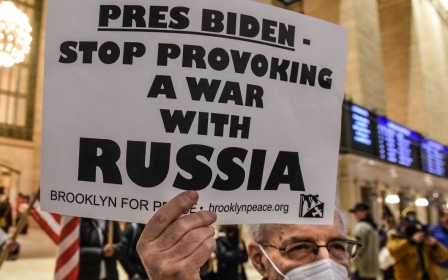

Its growing presence across Africa, the Middle East and elsewhere will facilitate the expansion of its global influence, using a wide range of tools ranging from arms sales, to energy deals, diplomacy and political and military advisers. States such as Venezuela and Cuba have been the most vocal in their support for Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, blaming the US and Nato for the crisis (although neither voted in support of Russia during the UN General Assembly vote on Wednesday).

Strategic partners

Since 2014, China has become an increasingly important partner for Russia, and they have developed a strategic partnership, primarily driven by economic and military cooperation, particularly arms sales and joint/multilateral military exercises. China is also an important market for Russian gas.

Moscow has been looking to maximise power and influence, in order to cement its great power status

To some extent, the two states have been pushed together: the imposition of a sanctions regime against Russia in 2014 forced it to turn to China for goods that it could no longer obtain from the West. Beijing has sought to take a neutral stance towards Moscow’s actions in Ukraine, calling for negotiations and abstaining in a UN Security Council vote condemning Russia.

China is Russia’s largest trade partner and the two have both been labelled as "strategic competitors" by the US. They have also set out plans to work together in space, announcing plans to jointly build an international lunar research station earlier this year. Russia has also sought to reinforce its links with China through support for institutions that sit outside of the US-led order, such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), headquartered in Beijing.

There has been tremendous continuity in Russian goals and ambitions over the past two decades. Moscow has been looking to maximise power and influence in order to cement its great power status. Its invasion of Ukraine is likely to derail this, pushing it towards international isolation.

This will see it seek to accelerate its move towards China and develop stronger ties across Africa and the Middle East, whilst consolidating its dominance in the post-Soviet space.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].