Al-Aqsa Mosque: The significance of one of Islam's holiest sites

Jerusalem's al-Aqsa Mosque is the third-holiest site in Islam, drawing tens of thousands of pilgrims from across Palestine and the wider Muslim world each year.

The mosque also serves as a symbol of Palestinian resistance and has often been targeted by Israeli forces in raids and by hardline groups wishing to rebuild a temple in its place.

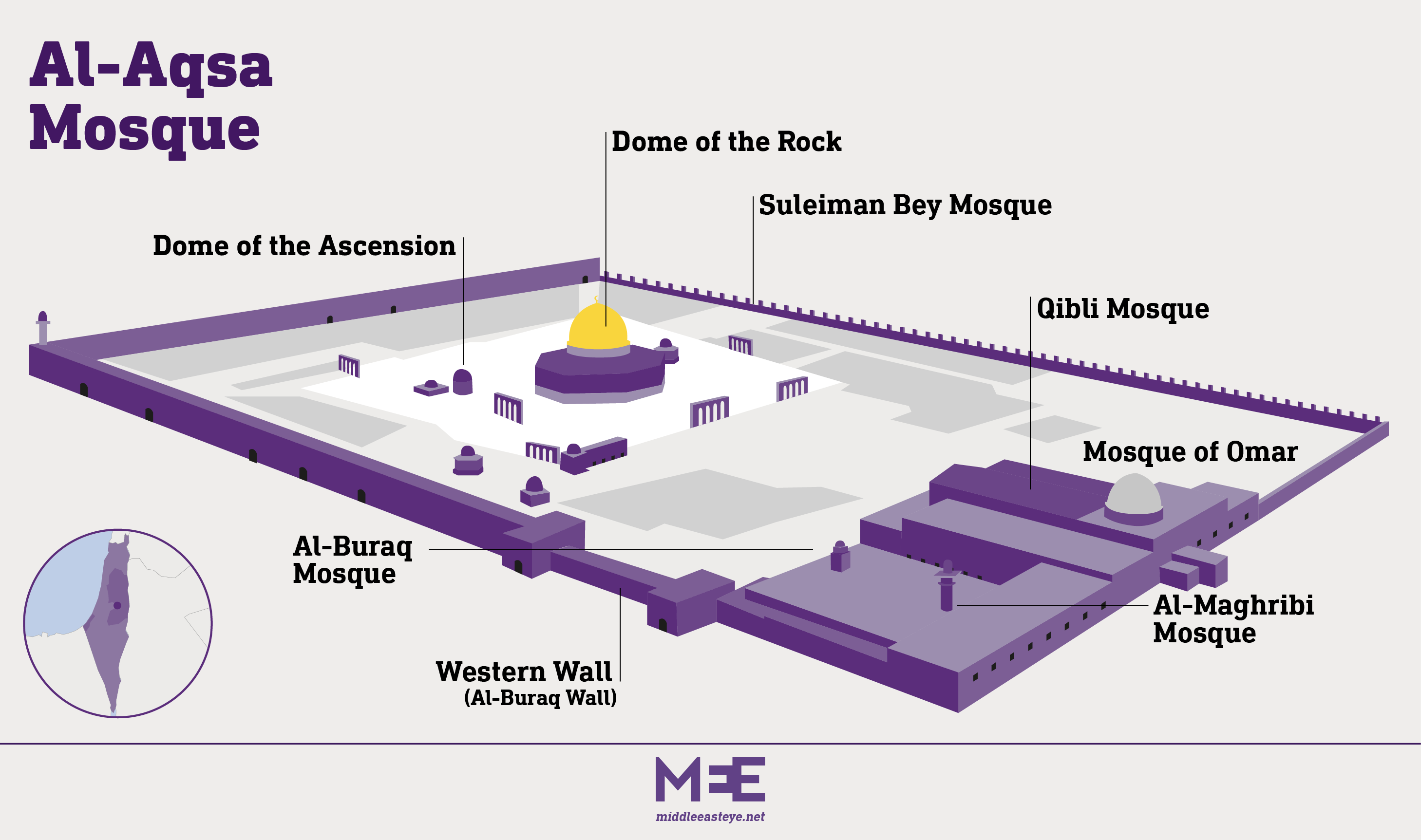

Spanning 14 hectares, the mosque includes the golden-domed Dome of the Rock, arguably one of Jerusalem's most recognisable landmarks, as well as the ancient al-Qibli Mosque, both of which are considered sacred.

The huge site, also known as Haram al-Sharif, or "noble sanctuary," in Arabic, traditonally had 15 gates, which allowed worshippers to pour into its grounds from the surrounding Old City of Jerusalem.

However, only 10 of these are still in use and are controlled by heavily armed Israeli soldiers and police officers.

Here, Middle East Eye provides a comprehensive guide to the holy site and answers key questions about its religious and cultural significance:

Where is it and what is the meaning behind the name?

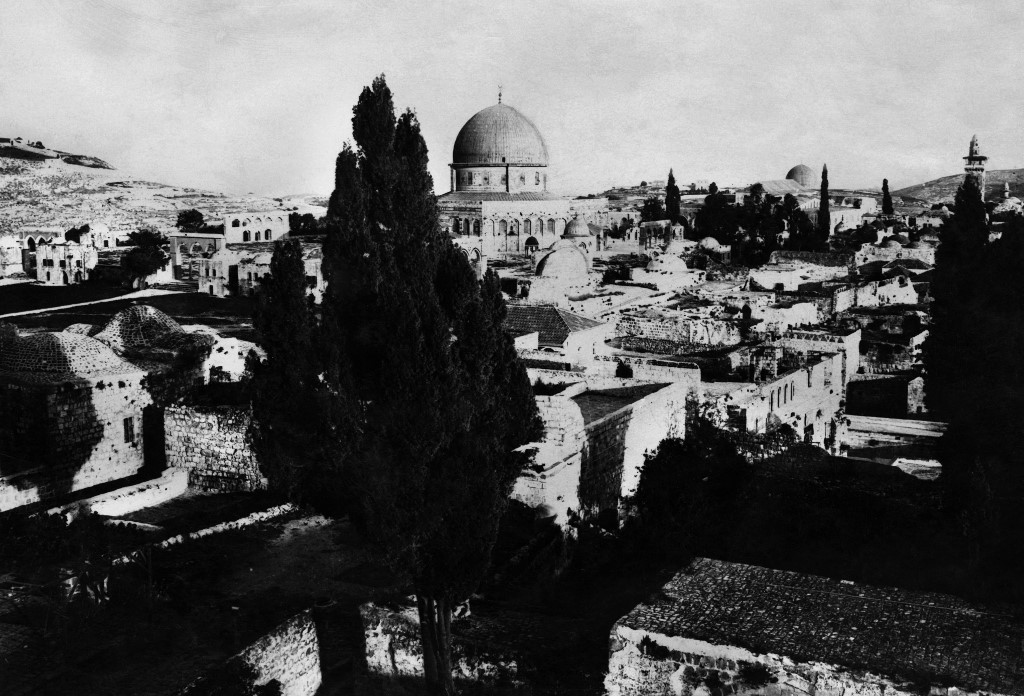

Located in the southeast corner of the Old City of Jerusalem, al-Aqsa's Dome of the Rock is visible from across the city.

The entire complex contained within the outer walls includes an area of 144,000 square metres, and has mosques, prayer rooms, courtyards and religious landmarks.

In Arabic, al-Aqsa has two meanings: "the furthest," which refers to its distance from Mecca, as mentioned in Islam's holy book, the Quran, and also "the supreme," referring to its status among Muslims.

Muslims also believe the site is where the Prophet Muhammad led his fellow prophets in prayer during a miraculous night journey, known as the Miraj.

Why is the site so important?

Besides its religious importance, al-Aqsa is a symbol of the culture and nationhood of the Palestinian people.

The glistening golden Dome of the Rock is recognisable to Muslims from around the world, and to pray at the site is considered to be a great privilege.

In the years before modern borders, pilgrimages to the Muslim holy cities of Mecca and Medina would include a stopover in Jerusalem.

The vast courtyards of al-Aqsa still draw tens of thousands of worshippers who gather every Friday for congregational prayers.

During the holy month of Ramadan, the area is especially busy with worshippers, who go to the mosque for the special nightly taraweeh prayers.

On Eid al-Fitr, which marks the end of the holy month of Ramadan, the mood of the area becomes more celebratory and includes singing, processions and the gifting of sweets to passers-by.

Who are the guardians of al-Aqsa?

+ Show - HideAl-Aqsa is administered by the Islamic Waqf, a Palestinian civilian administration that manages the site. Although Jewish Israelis are allowed to visit the compound, they can’t pray in it.

However, in recent years, some right-wing Israelis have challenged the rules, seeking, sometimes with force, to push the boundaries and pray on the site, causing invocations.

Known as the Mourabitoun and Mourabitat, Arabic for the steadfast or defender, this group comprised of men and women, aged anywhere between their 20s to their late 70s, are tasked with protecting and preserving the holy site.

The self-appointed guardians aim to protect the site from Israeli incursions and abuse from settlers. They keep their eyes peeled for far-right attackers, and Israelis who tour around the complex, as well as those who instigate confrontations with worshippers at the complex.

When they see settlers or Israelis coming onto the site, the mourabitoun will congregate and make their presence clear.

Their intitative stems from their belief that the status-quo at al-Aqsa is threatened.When they see settlers coming on to the site, they will call out loudly, gathering others and preventing them from staying on the premises.

The mourabitat are sometimes detained and arrested by security forces, with some facing interrogations and expulsions from the mosque.

For Jews, the site is known as the Temple Mount, where many believe two ancient Jewish temples once stood - the temple built by King Solomon (Suleiman in Arabic), which was destroyed by the Babylonians, and the second temple, destroyed by the Romans.

The site is home to the "Foundation Stone," where observant Jews believe the creation of the world began.

Since the Israeli occupation of East Jerusalem began in 1967, the site has been the subject of contention between Muslim worshippers and those groups that want to restore full Jewish control over the area.

What are some of the main landmarks at al-Aqsa?

Al-Aqsa is home to several landmarks associated with the city of Jerusalem and features some of the best-preserved historic architecture from the early Islamic period.

Besides the religious buildings and structures, there are 32 water sources on the site, including wells used for ablutions.

Several mimbars, or pulpits, and historic schools can also be found inside al-Aqsa's walls, some dating back to the Mamluk and Ayyubid eras.

The Dome of the Rock

According to Islamic belief, the Dome of the Rock contained the first Qibla, or direction towards which Muslims prayed.

According to Islam, al-Aqsa was one of the earliest mosques, following the Kaaba, the black cuboid structure in Mecca, where Muslims perform the Haj and Umrah pilgrimages and direct their prayers.

The mosque plays a key part in the Prophet Muhammad's miraculous night journey to the heavens, known in Arabic as al-Isra wa al-Mi’raj.

Muslims believe the Prophet Muhammad met the 124,000 prophets who preceded him and led them in prayer at the al-Aqsa mosque.

In Arabic, the Dome of the Rock is referred to as Qubbat al-Sakhra, and holds a religious and historical significance.

The Dome of the Rock throughout history

+ Show - HideSince it was built, the Dome of the Rock has come under various rulers and faced numerous transformations.

The mosque was reconstructed under the Umayyad dynasty between 688 and 691AD, and renovated several times under the Abbasids and Fatimids.

However, one of the major historical turning points for al-Aqsa was when the Crusaders occupied Jerusalem in 1099AD, turning the Dome of the Rock into their headquarters. Soon after, the building was covered in Christian iconography. However, when Salaheddin reconquered Jerusalem in 1187AD, the building was returned to its original function as a mosque once again.

Any trace of the Crusaders were removed from the Dome of the Rock and it was heavily renovated under the Ayyubids, who added wooden frames surrounding the Holy Rock of Ascension and fortified the buildings’ walls.

Due to the building’s importance, the Mamluks paid particular attention to restoring the mosque, especially the mosaics. Likewise, the Ottomans brought in mosaics made in Istanbul, assembling them in the mosque as well as opening new windows.

Other significant renovations came under the Hashemites, who coated the dome with gold-coloured aluminium sheets and had the Islamic typography restored.

The structure was commissioned by the Umayyad Caliph Abdul Malik ibn Marwan between 691-692CE, over a rock from which the prophet was believed to have ascended to heaven.

Islamic belief states that a divine ladder descended from the highest level of paradise to the Rock of Ascension. The rock stands around one-and-a-half metres above the floor, in a location called "the Prophet's chapel".

The Dome of the Rock is one of the earliest examples of Islamic architecture and forms the archetypal structure of later mosques and Islamic structures. Its octagonal structure has four entryways, and its interior is decorated with verses from Surah al-Isra in the Quran. These inscriptions are also some of the earliest surviving examples of the text of the Quran.

Inside the mosque, worshippers are met by grand stained glass windows, intricately decorated with Islamic motifs and typography.

The mosque is also home to one of the oldest surviving mihrabs, a niche in the mosque's wall showing the direction of prayer towards Mecca.

The Western Wall

One of the most important sites at al-Aqsa is the Western Wall, also known as the al-Buraq wall, on the southwest fringe of the mosque.

The wall is between the Gate of the Prophet and the Moroccan Gate, and the area also has a small mosque, which was constructed between 1307 and 1336CE.

Standing around 20 metres tall and 50 metres in length, the wall is believed to be where the Prophet Mohammed tied a winged horse-like creature, known as al-Buraq, before he ascended to heaven.

The Western Wall is sacred for Jews, who believe that it is the last remaining structure of the Herodian temple, which was destroyed by the Romans in 70CE.

Each year, tens of thousands of Jews gather and pray at the site, posting prayers between niches in the wall.

Al-Qibli Mosque

The silver-domed structure is towards the southern wall of al-Aqsa and is the first building constructed by Muslims at the site. It is considered one of the most significant structures on the site and is where the imam stands to lead worshippers in prayer.

When Muslims entered Jerusalem in 638CE, Islam's second caliph, Omar bin al-Khattab, and his companions ordered the construction of the mosque, in what was at the time a barren and neglected area.

Originally, the mosque was a simple building that sat on wooden trusses, but the structure that is seen today was first built by the Umayyad Caliph Walid bin Abdul Malek bin Marwan at the start of the eighth century.

Throughout history, the mosque has experienced numerous earthquakes and attacks, which have left a mark on the original structure.

Its last major refurbishment was during the Ottoman period, during which the sultan Suleiman the Magnificent restored a number of sites within the mosque area, installing plush carpets and lanterns.

Today, al-Qibli Mosque has nine entrances. The main entrance is in the middle of the building's northern facade. Inside, stone and marble columns tower high, supporting the structure.

The stone columns are ancient, while the marble ones were part of renovations in the early 20th century.

With enough room to host around 5,500 worshippers, the mosque has a length of 80 metres and width of 55 metres.

Inside, the mosque's dome is wooden and the columns are decorated with glass mosaics, which feature illustrations of plants, geometric patterns and verses from the Quran.

How has the site become a symbol of Palestinian resistance?

For Palestinians, al-Aqsa serves more than a religious function and is the centre of the cultural life, where they go to celebrate, congregate and mourn.

Many Palestinians who frequent the mosque have been visiting since they were young, and, for them, al-Aqsa is the most widely recognised symbol of their country.

Many also break their fasts at the mosque during Ramadan and go to pray there on Fridays, depending on the restrictions Israeli occupation forces have in place.

Another reason for the Palestinian attachment to the mosque is the threat to its existence posed by hardline groups who want the area to be the home of a rebuilt temple.

Despite opposition to the idea by mainstream Jewish religious leaders, calls to rebuild the temple have been getting louder in recent decades and have drawn religious and political support.

Attacks on al-Aqsa

+ Show - HideDeliberate attempts have been made to attack al-Aqsa throughout history, in a move described by the UN as constituting ‘blatant desecration of the Holy places’.

In a statement published in 1988, the UN denounced the stormings of al-Aqsa following a series of attacks and called them a violation of international law, citing the Hague Convention of 1907 and the fourth Geneva Convention of 1949.

“The Israeli occupation authorities’ annexation of Arab Jerusalem and their imposition of Israeli law there represent in themselves a dangerous and flagrant act of aggression against the rights and feelings of Musliums,” the statement read.

One of the most notable attacks on al-Aqsa was the attempt to burn it down in August 1969, as well as Israeli excavations around the site from 1967 onwards, which resulted in cracks forming in its walls.

Repeated attempts by Israeli Knesset members to forcibly enter the site to pray there have also caused serious confrontations. In January 1986, 16 members of the Knesset made their way into the site, igniting an armed raid and an attempt to blow up al-Aqsa, in accordance with a plan put together by Rabbi Meir Kahane.

A number of explosives were uncovered at the holy site in May 1980, stoking further threats against Palestinians at al-Aqsa.

Since this point, Israeli forces, settlers and far-right groups have stormed al-Aqsa and damaged the interior of the site.

The site is home to what is believed to be Palestine's first museum, the Islamic Museum, which was established in 1923 and contains rare archaeological and artistic collections, as well as manuscripts of the Quran.

History of tensions at al-Aqsa

The al-Aqsa mosque, along with the rest of East Jerusalem and the West Bank, was captured by the Israelis during the 1967 war.

After the conquest and subsequent occupation, Israeli authorities allowed Jews to perform prayers at the Western Wall but not inside al-Aqsa.

As a result of those restrictions, Jews and foreign tourists can enter the site only through the Maghribi Gate.

Nevertheless, there have been countless attacks on al-Aqsa, mostly by Zionist groups, but Israeli authorities have also been criticised for carrying out excavations and demolitions in the area.

During the first Palestinian Intifida in 1988, Israeli forces attacked Muslim worshippers who were in the courtyard outside the Dome of the Rock, using teargas and rubber-coated steel bullets, and injuring many.

One of the most notable recent incidents happened in September 2000, when then Israeli opposition leader Ariel Sharon toured al-Aqsa, surrounded by heavily armed Israeli soldiers.

The act was seen as a major provocation and inflamed tensions, with many attributing the start of the Second Intifada to the incident.

Why do Israeli forces storm al-Aqsa?

+ Show - HideIsraeli forces tend to storm al-Aqsa during periods of escalating tensions, Jewish holidays or Israeli national days, or to disperse large crowds of Palestinians.

Over the years, Palestinians have also decried an uptick in assaults against them during the holy month of Ramdan, which many Muslim worshippers spend praying at the site.

During the two-day Jewish holiday of Purim, Israeli settlers stormed al-Aqsa under the protection of Israeli special forces. The move, which came amidst restrictions on access to the site for Palestinians, was seen as provocative and denounced by worshippers.

In recent years, the number of Jewish worshippers quietly praying on the site has increased, with Israeli far-right activists pushing for an increased Jewish presence at the site, despite a longstanding joint guardianship agreement between Israel and Jordan that bars non-Muslim prayer at the site.

Some right-wing Israeli activists have advocated for the destruction of the al-Aqsa Mosque to make way for a Third Temple.

When Israeli forces storm al-Aqsa, worshippers on the site are met with tear gas, rubber-coated steel bullets and face arrests and beatings.

In May 2021, when Israeli forces stormed al-Aqsa, many of the Dome of the Rock’s historic stain glass windows were smashed, and skunk water used on those praying within the mosque.

Medics have reported skin rash, nausea, shortness of breath and headaches after exposure to skunk water and people suffering from shortness of breath have been taken to hospitals for therapy.

In 2015, nationalists entered the site to mark the anniversary of Israel's occupation of East Jerusalem, provoking Palestinian protests and Israeli military suppression of any dissent. Known as "Jerusalem Day," 17 May is a date that usually sees an uptick in aggression.

Muslims frequently face difficulties when entering al-Aqsa due to Israeli security measures with young men, especially, blocked from entering during periods of heightened tensions.

Muslims in the West Bank can only enter the site with a permit: restrictions vary, including a total bar on certain days.

The atmosphere is particularly tense during Ramadan, when Israeli authorities can place bans on Palestinian worshippers who want to pray at the site, or when members of the Knesset tour the area.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].