France elections 2022: Should Muslims boycott the vote or take a chance on the left?

French Muslims are puzzled. Many of us don’t know what to make of the current presidential election.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has temporarily shifted the political conversation away from the daily obsession with Islam and Muslims, giving us a chance to pause and consider whether - for once - voters will be given an opportunity to make a decision based on long-term issues, such as climate change, education and health.

But the suspense hasn’t lasted: new polls show the far right remains the leading political force in France, and its programme is focused mainly on immigration and Muslims.

Muslims who have experienced five years of political harassment under the Macron regime have a choice to make

But something has changed from years past: racism is not hidden any more. Politicians don’t pretend any more. The government doesn’t try to save face any more, as it validates far-right tropes about minorities.

As the racist and conspiratorial “Great Replacement” theory is discussed by mainstream politicians, and the state applies a racist and ethnically selective policy on refugees, no voter can be fooled any more as to which “republican values” are at stake in this race for power.

And as much as this mass persecution of minorities is harmful and destructive for civil society groups, communities and families, the discursive shift is a positive development, as it clarifies the political game.

The key players

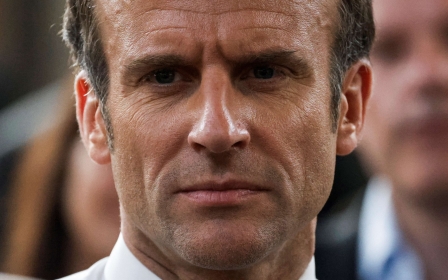

In this game, there is a president, Emmanuel Macron, who was elected to oppose the far right, only to methodically apply its agenda by condoning police violence; supporting destructive economic and social policies; threatening and harassing any civil society group that dares to express dissent; and destroying and dividing all Muslim organisations that refuse to accept second-class status for Muslims. All the while, France poses at the international level as the torchbearer of freedoms, with little success.

Macron appears to be betting on the country’s post-Covid-19 political amnesia and on the electoral disengagement of the unhappy masses, aiming to be re-elected as the lesser evil.

Then there is a left-wing candidate, Jean-Luc Melenchon, who is leading a dynamic campaign and performing well in the polls, with his support standing at more than 15 percent. And yet, he has struggled to distance himself from his past support for the Putin and Assad regimes.

He is also paying the price for a divided left, has failed to include important minority voices in his campaign, and is demonised by the many media outlets that give more exposure to right-wing candidates.

Finally, there is Marine Le Pen, the far right’s most potent candidate, who was initially shaken and destabilised by Eric Zemmour’s campaign as he chipped away at her support, before taking stock and repositioning herself as the “reasonable patriot”.

Le Pen is patiently reclaiming her position as Macron’s main challenger, garnering 22 percent in the polls. She could ultimately benefit from broad support among conservatives and reactionaries on the right, alongside all those who radically oppose Macron.

Evolving positions

This situation is making for perhaps the most uncertain election in French history. And within this game, Muslims are still attempting to position themselves.

While around 80 percent of Muslims have voted for left-wing parties in past elections, positions have evolved over the past decade for both political and socioeconomic reasons.

As Muslim families reach middle-class status, their issues of concern might shift. In addition, left-wing candidates have a long tradition of betrayal on issues such as addressing Islamophobia and police violence.

Still, Melenchon’s evolution on these issues has been attracting voters, and grassroots activism around his campaign, while remaining critical on occasions and non-naive, makes it possible for him to position himself as a genuine alternative.

From politically conscious abstention to taking another chance on a left-wing candidate, Muslims who have experienced five years of political harassment under the Macron regime have a choice to make.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].