Al-Aqsa Mosque: Israeli raids and incursions explained

Israeli settlers and far-right activists, nearly always protected by the police, enter al-Aqsa Mosque on an almost daily basis, showing complete disregard to the site's Palestinian Muslim administration and the thousands of worshippers who are usually at the site.

The controversial incursions have long been a cause of tensions and violence against Palestinians in East Jerusalem and beyond.

To Palestinians, they are viewed as part of a decades-old strategy by the Israeli state and right-wing groups to "Judaise" the city and rid it of its native Islamic and Christian Palestinian heritage.

To far-right Israeli groups, they are the first step to lay the foundation for the destruction of al-Aqsa and replace it with a Third Temple, which they believe will be built atop the mosque.

Here, Middle East Eye looks at the history of the Israeli incursions at al-Aqsa, and why they are controversial for Palestinians and Muslims.

What are Israeli incursions in al-Aqsa?

Palestinians refer to the unsanctioned entry of any Israeli into al-Aqsa Mosque complex as a settler incursion.

As part of an understanding between Jordan – the custodian of Islamic and Christian sites in Jerusalem – and Israel, non-Muslims are allowed to visit al-Aqsa under the supervision of the Waqf, a joint Jordanian-Palestinian Islamic trust that manages the affairs of the mosque.

The agreement stipulates that only Muslims are allowed to pray in it while Jews can perform prayer by the Western Wall. Meanwhile, Israeli authorities retain security control over the mosque.

However, Israel has long ignored this delicate arrangement, often referred to as the "status quo" and bypassed the Waqf.

In recent years, Israelis forces, settlers and high-profile politicians have repeatedly raided the mosque without Palestinian permission.

The incursions have at times led to large confrontations and subsequent Israeli crackdowns on Palestinians.

Before 2000, the Waqf controlled the visits of non-Muslims to the site through a booking system. This was rescinded by Israel after the Second Intifada, or uprising, which ended in 2005. Now, dozens of Israeli settlers and far-right activists tour the courtyard of the mosque almost on a daily basis, flanked by Israeli forces.

What do the Israeli far-right groups want?

There are several far-right groups, mostly religious-Zionists, that organise incursions at al-Aqsa Mosque.

They are sometimes referred to as the "Temple groups" and include organisations such as The Temple Institute and the Temple Mount and Eretz Yisrael Faithful Movement.

Israelis refer to the incursions as the "ascension to the Temple Mount", with some demanding Israel assert full Jewish sovereignty over the site, allowing Jewish worship and ritual sacrifice to take place.

Some also advocate for the destruction of al-Aqsa Mosque, where they believe two ancient Jewish temples once stood, to make way for a third temple.

Followers of other religious sects, mainly ultra-Orthodox Jews, prohibit such visits due to the holiness of the site in Jewish tradition.

What happens during the incursions?

The incursions are planned every day except Fridays and Saturday. In the past, settlers avoided entering the mosque during Muslim holidays, but this has changed in recent years.

Protected by heavily-armed police, the settlers enter the courtyards of the mosque in two different shifts to recite prayers, perform rituals and hold presentations to tour members.

The first tour is normally between 7:30am and 10:30am local time and the second is between 1pm and 2pm. There are no Muslim prayers at those times, and the mosque is normally nearly empty of worshippers.

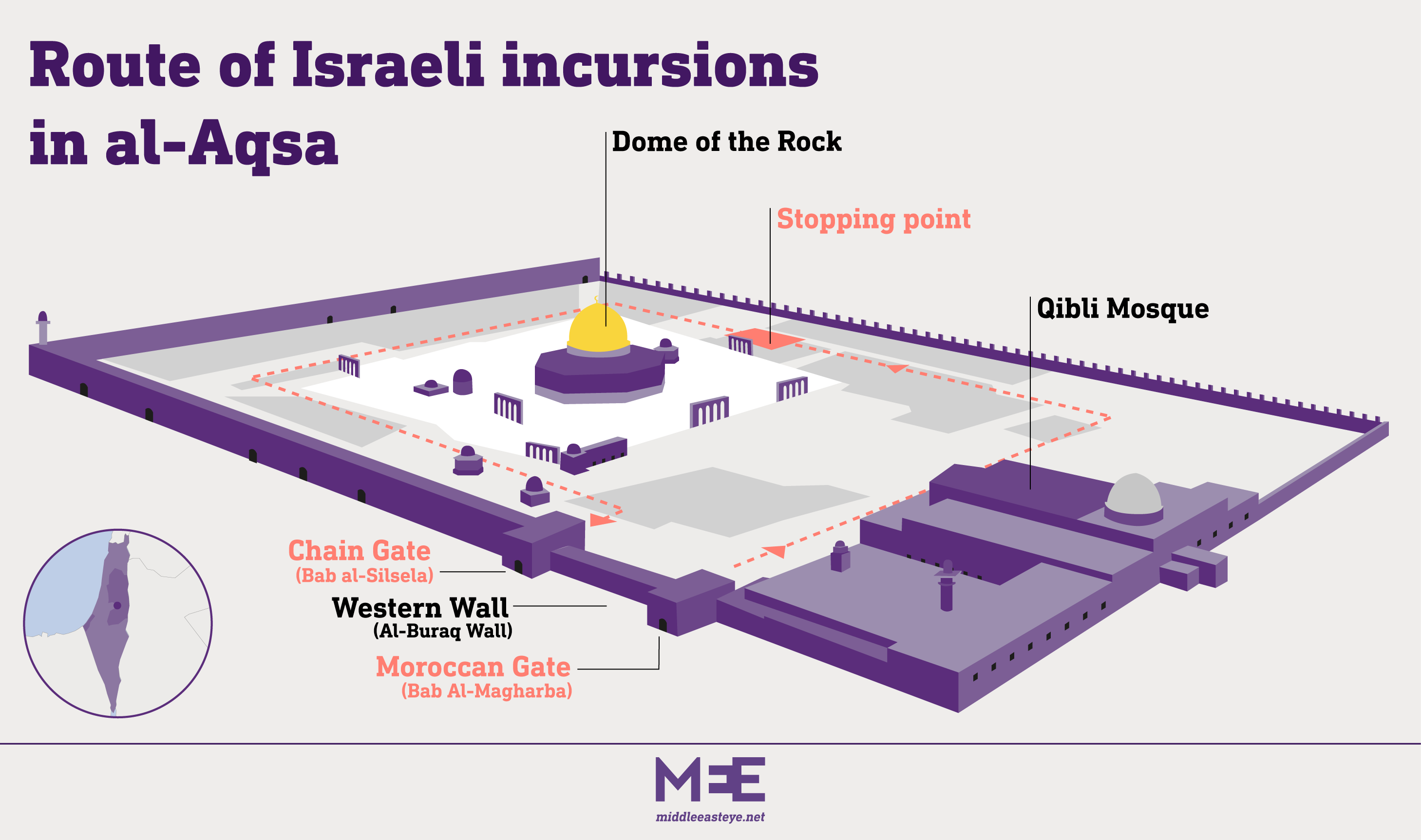

Each tour lasts from 30 minutes to an hour, starting from the Moroccan Gate (Bab Al-Magharba) on the southwestern end of the complex.

Settlers then head towards the southeastern section, passing across the Qibli prayer hall with the silver dome, the main building on the site and from where congregational prayer is led. They then walk to the northeastern and western sections, before circling back to where they started and exit from Chain Gate (Bab al-Silsela).

In the past, tours used to last 10-15 minutes and start at Moroccan Gate and end at Chain Gate a few metres away. The tours have grown steadily over the years despite repeated objections from Palestinians.

To avoid tensions in the past, Israeli police have tried to stop Jewish visitors from praying at al-Aqsa, as non-Muslim prayer is a highly sensitive issue.

However, with no Israeli laws explicitly preventing Jews from doing so, this policy seems to have changed recently.

The Waqf has documented instances where prayers and rituals were carried out during the raids. In August 2021, the New York Times reported that the Israeli government had "quietly" been allowing Jewish prayer without publicising it.

When did the incursions start?

Raids on al-Aqsa Mosque started immediately after Israel occupied the eastern section of the city in 1967, along with the West Bank and the Gaza Strip.

Soldiers who captured the city entered the mosque courtyards on 7 June 1967 while raising the Israeli flag and banned Muslim prayer for a week.

In 1982, American-Israeli Alan Goodman, who had links to the violent pro-settler Kach movement, entered the compound with an automatic rifle and fired indiscriminately inside the Dome of the Rock, killing two Palestinians and wounding nine others.

In 1990, an Israeli group known as the "Temple Mount and Eretz Yisrael Faithful Movement" attempted to place a cornerstone for the Third Temple in the compound. Israeli forces responded with live fire to quell confrontations and protests by Palestinians, killing more than 20 and wounding at least 150.

Later on, the Israeli government authorised the opening of a tunnel to the Western Wall, under the foundations of the al-Aqsa complex, and continues to sponsor archaeological digs in the vicinity of the mosque operated by settler groups.

In September 2000, then-opposition leader Ariel Sharon stormed al-Aqsa Mosque, backed by hundreds of heavily armed officers. His visit, seen by Palestinians as highly provocative and insensitive to the sanctity of the mosque, sparked the five-year Second Intifada.

Citing security reasons, Israel revoked the Waqf's administration of visits by non-Muslims in the aftermath of the Intifada.

This opened the way to more organised tours by Israeli settlers and far-right activists, protected by police. From around 2017 onwards, the incursions became organised in the daily tour format they exist in today.

Dozens of people join each tour, with the number rising to hundreds on Jewish holidays, such as Passover, Purim, Jerusalem Day and others. For example, on Jerusalem Day in 2018, more than 1,600 settlers raided the mosque.

The number of visitors has grown steadily over the years. In 2009, 5,658 settlers entered the mosque in such tours. In 2019, just before the Covid pandemic, the number rose to 30,000, according to some estimates.

How do Palestinians view the incursions?

Palestinians say the incursions are an attempt by ultra-nationalists to claim religious ownership of the holy site and remove Palestinian culture and religion from al-Aqsa. The mosque, the third-holiest site in Islam, is revered by Muslims globally and has become a symbol of Palestinian culture and existence.

Praying at the site is believed to bring greater reward, according to Islamic traditions, and Muslims usually save up for several years to visit the holy site. To many Palestinians, protecting it is both a religious and a national duty.

By allocating specific times for Israeli entries, and allowing them to pray there, Palestinians fear the groundwork is being layed to divide the mosque between Muslims and Jews, similar to how the Ibrahimi Mosque in Hebron was divided in the 1990s.

Israel's control of East Jerusalem, including the Old City, violates several principles under international law, which stipulates that an occupying power has no sovereignty in the territory it occupies and cannot make any permanent changes there.

To stop the incursions, Palestinians have long organised what is known as Ribat, a social and religious sit-in activity in which worshippers gather in the mosque for extended hours and even days.

The purpose of the Ribat is to populate the premises of the mosque at all times to prevent Israeli settlers from entering it, especially during Muslim holidays.

Israelis police have on multiple occasions raided al-Aqsa to clear it of worshippers participating in Ribat, particularly ahead of Jewish holidays.

The most recent raids were in May 2021, when Israeli forces used teargas, stun grenades and rubber-coated steel bullets inside the courtyards of the mosque during Ramadan, injuring hundreds.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].