Russia-Ukraine war: The westerners who went from fighting Islamic State to aiding Kyiv

As international military intervention grew against the Islamic State group (IS) in late 2014, Aiden Aslin decided to join the fight.

The young British man made the trip to Syria in 2015 and spent two years fighting there with Kurdish fighters in the People's Protection Units (YPG) until 2017.

Five years later, the now-Ukraine marine finds himself in Russian custody in Mariupol, after he moved on from the battle against IS to join a different fight.

The former caretaker is one of the dozens of western fighters who once supported Kurdish forces in Iraq and Syria and are now signing up to fight Russian forces in Ukraine, as Moscow's invasion of its neighbouring country nears the end of its second month.

In 2018, Aslin went to Ukraine, where he met his fiancee, bought a house and joined the Ukrainian marine corps.

A friend, Brennan Philips, told Middle East Eye the move was due to Aslin's love for people and "indignation to Russian fascism".

"That's why he went to Ukraine. He saw an opportunity there to start a career as a marine and took advantage of that," said Philips, a former US soldier who spent time with Aslin in Syria's autonomous Kurdish region, known as Rojava.

After weeks of fierce fighting, Aslin, with his Ukrainian unit, surrendered to Russian forces in Mariupol last week. A video posted by Russian state media showed him with cuts and bruises on his face.

Aslin was not a volunteer or a mercenary with any paramilitary groups in Ukraine, which include the infamous Azov battalion, Philips insisted, and his safety is now the responsibility of the Russian forces.

"If anything happens to him now, it is a very well documented war crime, and a violation of the Geneva conventions, which he is entitled to," Philips said.

Different wars

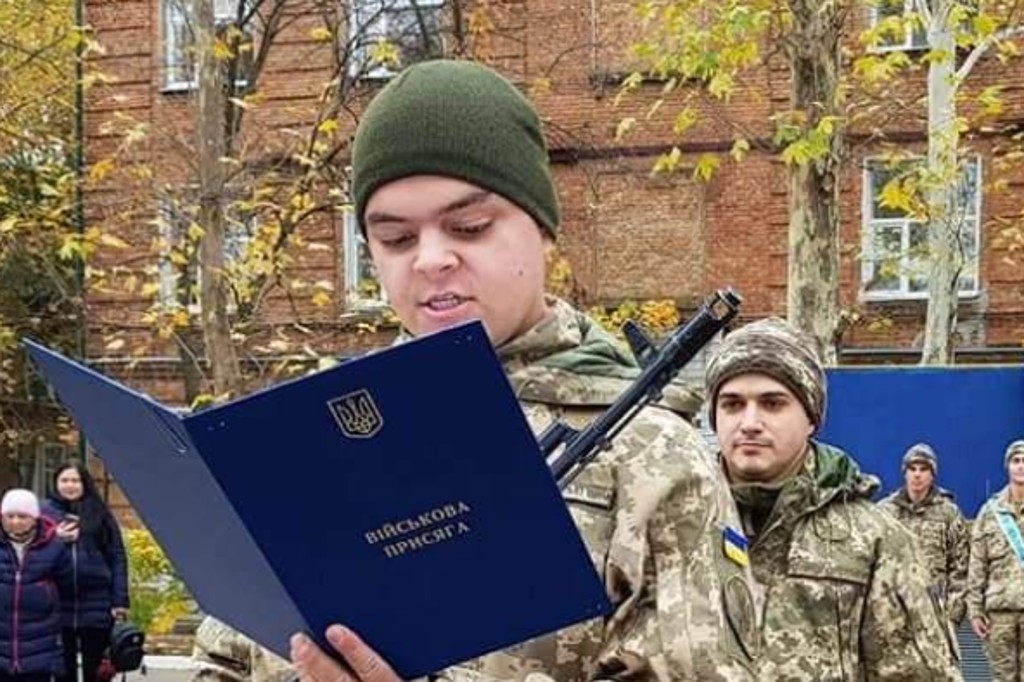

After the Russian invasion of Ukraine started in February, thousands of foreign fighters were called upon to join the fight on both sides.

Many of those fighters operated in Syria, especially in the fight against IS.

Macer Gifford, a former British volunteer who took part in the campaign to recapture Manbij and Raqqa from IS, is now setting up medical training for the Ukrainian self-defence.

However, he said, unlike in Syria, he wasn't in Ukraine to support the army "because they were already well supplied by the West and already well trained".

He is also trying to bring medical aid to the country where he spent a few weeks before getting stuck in the UK after contracting Covid.

"They [Ukrainians] very much remind me of the spirit of the thousands of young men and women who joined the Kurdish forces to defend their homeland. I got the same vibe in the home guard units, in particular those who volunteered to protect their country," Gifford told MEE.

Ryan O'Leary, an Iowa National Guard veteran who fought with and trained Kurdish forces against IS for four years in Iraq, shared a similar view.

"To be honest, they are really similar. Both Ukrainian armed forces and Kurds have the same mentality when it comes to fighting and their homeland," O'Leary told MEE.

However, he noted that Ukrainian forces are far more organised, "predominantly because all Ukrainian forces, even the militias, fall under the government instead of political parties".

"Fighting is pretty very different though. Over here we fight street by street, village by village through the woods... the front lines move so much, the troops move so much for the Russians, that there is a lot more violence, so it's a lot more brutal," O'Leary said.

The two conflicts also differ in how the western public views them, Philips said.

"Not a lot of people in the western world have a connection to the Middle East outside of maybe military veterans who served in the region or their families that come from there," Philips said.

"It's just, we have so many ties there. I mean, this is a European country, just like Germany or France, or the UK. It's so important to make that distinction. And that's one of the things that are different, but also that they have a vast wealth of human capital."

More solidarity for Ukraine

Philips' sentiment is echoed by Gifford, who agrees that there is more solidarity from ordinary people in the UK towards Ukraine than towards the Kurds.

"I know there'll be a lot of people out there frustrated by being annoyed that Syria and Iraq were less on the Europeans' minds than, say, Ukraine."

Although Gifford believes it's a shame there is less official support for volunteers in Syria than there is for Ukraine, he chooses to ignore that for the moment and focus his effort on "actually helping the Ukrainian people".

Chris Scurfield, the father of Konstandinos Erik Scurfield, who died fighting with Kurdish forces against IS in 2015, said the UK has previously tried to prosecute British fighters who took up arms against the group in Syria, and was shocked when the UK foreign secretary, Liz Truss, said she would support volunteers going to Ukraine.

"It put volunteers on the political map because the Ukrainian war marks a complete turnaround, where the UK is leading the anti-Russian war physically and economically and initially encouraged volunteers to go fight Russia," Scurfield told MEE.

Truss later said it was UK travel advice that people should not go to Ukraine.

"I was shocked with the initial response because it represented such a clear break in policy and showed a suppressed antagonism towards Russia," Scurfield said.

"Exactly how the UK government will treat returning Ukrainian volunteers is yet to be determined."

Scurfield's scepticism towards the UK government's policy comes from previous experience endured by fighters returning from Syria.

"[Some volunteers] will be forever subjected to UK state pressure of arrest. Some volunteers understandably sought new countries to live in, where their lives and contributions were more valued," he said.

"Ukraine enjoys total western support, but in Rojava they were and still are denied the oxygen of publicity, refuge and ultimately western support, despite both conflicts standing for 'western values'."

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].