Macron vs Le Pen: Why it's hard for French working-class neighbourhoods to choose

"Those who say they will vote for the far right on April 24, 2022, please unfriend me immediately," warns M'hamed Kaki on his Facebook page.

A French citizen of Algerian descent, Kaki is the president of the Les Oranges organisation, dedicated to retelling the story of how immigrants positively contributed to French history. He arrived in France at the age of nine, and the horrors of racism are still ingrained in his memory.

For many years, Kaki lived with his family first in a slum then a housing estate in Nanterre, a commune some 11km northwest of the centre of Paris. Like many immigrants, he has been confronted with ostracism, hatred and racial profiling since he was young.

It is no wonder that Kaki cannot envisage seeing the National Rally party (RN) candidate, Marine Le Pen, win the election and constitutionalise xenophobia under the guise of popular preference.

So, when some of his acquaintances tell him they are voting for Le Pen, Kaki sees red. "It's a very serious matter, because these people do not measure the danger of such a choice," he told Middle East Eye.

Tempted to vote Le Pen

According to Kaki, voters in working-class neighbourhoods, particularly North Africans, who are preparing to give their votes to Le Pen think that she could be better than incumbent President Emmanuel Macron, who came top in the first round of voting, with 27.84 percent of the votes, ahead of Le Pen who came second with 23.15 percent.

The presidential campaigns have been centred on the economy, especially the cost-of-living crisis in the country, but it has also been marred by divisive rhetoric on immigration control.

"Some Muslims consider Le Pen less Islamophobic, for example," said the president of Les Oranges.

'I am afraid we will see a large number of abstentions in working-class neighbourhoods or people tempted by the Le Pen vote against Macron'

- Madjid Challal, municipal councillor

Worried about the idea of seeing what he considers "a far-right tsunami in France," he tries to mobilise voters, against both abstention and the RN.

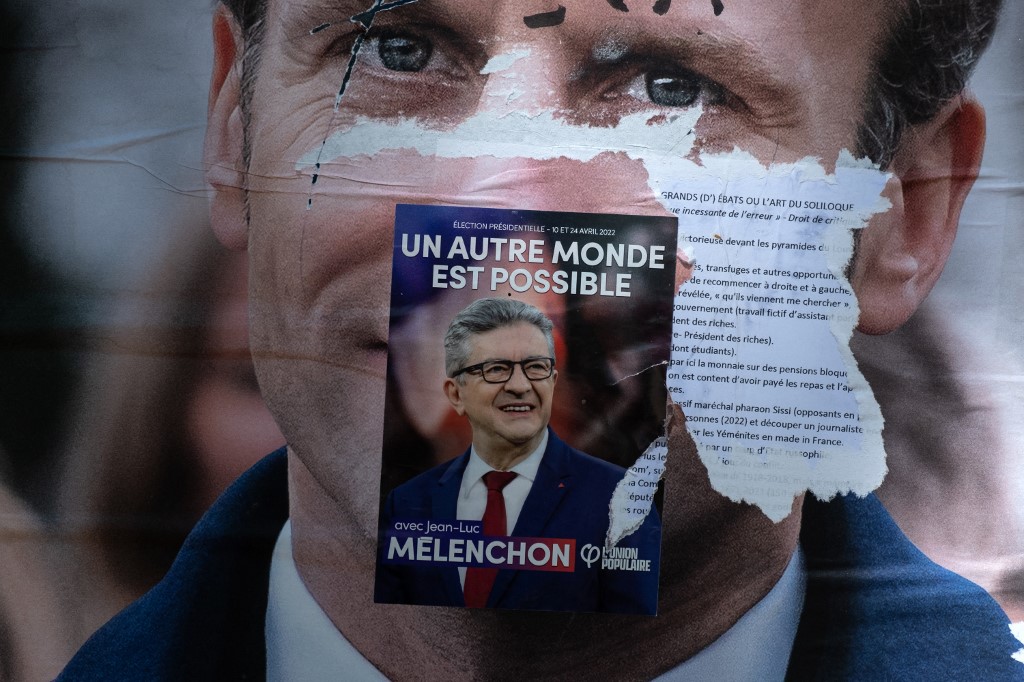

"People must go en masse to the polling stations, and no voice should go to the far right," Kaki said, echoing statements by Jean-Luc Melenchon, the far-left candidate for the France Unbowed party, who came third in the first round with just under 22 percent.

Melenchon garnered the highest number of votes in Nanterre, as well as in the entire Ile-de-France region in north-central France.

According to Madjid Challal, a municipal councillor affiliated to the Europe Ecology - The Greens party in Epinay-sur-Seine in the northern suburbs of Paris, Melenchon largely benefited from the vote of working-class neighbourhoods despite the division of the left, which arguably prevented him from securing a place in the second round.

In Challal's commune, for example, Melenchon obtained 9,283 votes (compared with 6,061 at the end of the first round of the 2017 presidential election), which accounts for three times more votes than Macron and six times more than Le Pen.

"This result shows the gap between politicians and reality in working-class neighbourhoods. I live in a working-class area where most of the inhabitants gave their votes to Melenchon. I myself voted for him. It's not a political vote but rather a socioeconomic one," Challal told MEE.

"People choose the programme that meets their social aspirations. France Unbowed is very strong in this regard because the party has been able to understand social and community mindsets.

"Melenchon has been the only one, for example, who defended Muslims. This explains the results he obtained in the suburbs. In one polling station, I saw an impressive number of women wearing headscarves. Unheard of," he added.

After having treated the hijab as a "rag on the head" with which Muslim women "stigmatise themselves," Melenchon has fundamentally changed his positions on religion, in particular Islam. This was obvious, for example, when he took part in the March against Islamophobia in November 2019 and defended the freedom to wear the hijab without restrictions.

According to a public opinion poll by the French polling company IFOP, the Muslim electorate voted largely in favour of Melenchon in the first round of the 2022 elections (69 percent of Muslim voters), far ahead of Macron (14 percent) and Le Pen (7 percent).

Nevertheless, like Kaki, Challal fears that the momentum generated by Melenchon's candidacy will disappear in the second round. "I am afraid we will see a large number of abstentions in working-class neighbourhoods or people tempted by the Le Pen vote against Macron," he said.

Describing the presidential finalists as "evils," he believes that, with one or the other, the situation of the working classes will be unchanged and that they will continue to suffer from the same social problems and Islamophobia.

Under Macron's five-year term, and in a context of rising anti-Muslim violence in the country, the government has taken a series of measures that have been perceived by some Muslims and human rights defenders as discriminatory against the minority, such as the project for a "vigilance society against the Islamist hydra," the law against "Islamist separatism," or the closure of mosques and civil society associations defending Muslim rights.

"Personally, I cannot support the neo-liberal policy defended by Macron, just as I do not agree with the racial-consiousness policy of the National Rally. It's out of the question," said Challal, who intends to vote blank despite calls from the left to block Le Pen with a Macron ballot.

The leader of the Greens party, Yannick Jadot (4.6 percent in the first round), the candidate of the Socialist Party Anne Hidalgo and the communist Fabien Roussel all called for a transfer of votes to Macron.

"Left leaders are schizophrenic. They refused to unite because of ego issues in the first round, and they are all now calling for Macron to be voted for, even though they did not stop criticising him during the election campaign," said Challal.

Abandoned 'like plague victims'

In Vigneux-sur-Seine, a city that had been under communist rule until 2001, Farid (not his real name), an assessor in a polling station, almost pulled his hair out when he heard Roussel say in the aftermath of the first round that to beat the extreme right it was necessary to opt for Macron.

"If, like Hidalgo and the other left-wing leaders, he had refrained from running, it was Melenchon who could have won and blocked the far right in the first round," Farid said.

A municipal agent for 20 years and resident of L'Oly, a housing estate with 1,229 housing units, Farid has witnessed the deterioration of his neighbourhood, the impoverishment of its inhabitants and their ghettoisation.

"People here feel completely abandoned by the authorities, almost like plague victims," he told MEE, gazing up at the huge towers that block the horizon, literally and figuratively.

Near the Aime Cesaire social centre, the bus stop connects L'Oly to the centre of Vigneux-sur-Seine and neighbouring towns, such as Montgeron and its two large supermarkets or Villeneuve-Saint-Georges, where the intercommunal hospital is located.

Zohra, a single and unemployed mother who lives in L'Oly, usually takes the bus to do her shopping because she does not own a vehicle. "With the price of fuel right now, I'm glad I don't have a car. Instead, there's my cart. I fill it as I can," she told MEE, lamenting the loss of her purchasing power due to inflation.

Under the presidency of Emmanuel Macron, she also lost 5 euros ($5.40) in housing assistance, following a 2017 reform. Her children at the end of their schooling have found neither an internship nor a job.

"Besides, because of the separatism law, I feel like a terrorist when I walk down the street with my headscarf on," she said.

'Macron, for whom I voted in 2017, is ultimately not very different from Le Pen. She is against foreigners. He is the president of the rich,'

- Farid, municipal officer

So like all her neighbours, Zohra did not hesitate to vote for Melenchon in the first round. In Vigneux-sur-Seine, the candidate of France Unbowed also came out on top, with 41.06 percent of the votes.

"He was especially popular in the suburbs," said Farid, still undecided on what he will do in the second round. "We have a choice between plague and cholera. Macron, for whom I voted in 2017, is ultimately not very different from Le Pen. She is against foreigners. He is the president of the rich," said the municipal agent.

Zohra, who has given up on returning to vote in the second round, is fatalistic. "I am an immigrant, and I am poor. So whether it's Macron or Le Pen, nothing will change for me," she said.

A more optimistic Challal thinks that the election of Le Pen may not be a bad thing, in the sense that it could cause a republican surge that would thwart the conduct of Le Pen's mandate.

"If she wins, all the republican political parties will mobilise to win the legislative elections [planned for June] and block her in the Assembly. People around me believe in this perspective of a healthy third round," Challal said.

*This article was first published in French on Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].