The mysterious history of the Mamluk carpets that dazzled the Mediterranean

Persian carpets are renowned around the world for their quality and intricate designs. However, they are not the only antique carpets from the Middle East that became famous for their exceptional qualities. From the second half of the 15th century, numerous carpets of unparalleled beauty and various designs started appearing in prominent cities around the Mediterranean basin.

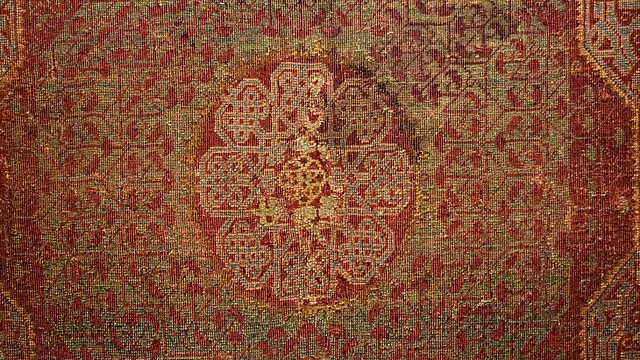

The carpets featured vibrant colours and were produced with near-perfect execution. One outstanding feature was that their wool was spun in an S-shape, rather than the traditional Z-shape, which was common at the time.

The carpets soon began to crop up from Granada, in the seat of the Nasrid Sultanate in a vanishing Al-Andalus, all the way to Jerusalem, including Florence and the Vatican.

For centuries, debate has swirled around the origins of these carpets, which were markedly different to the already well-known Persian or Turkish-Ottoman designs. Only in recent years have scholars managed to trace their origins - to Cairo, under the reign of the Mamluk Sultan Qaitbay (1468–1496), a great patron of the arts.

“When carpet studies began in the late 19th century, [the carpets] were all called Persian. And only in a later period it became possible to distinguish between Persian, Turkish and [those of] other provenances,” says Alberto Boralevi, a well-known antique carpet dealer, from a family business active in Venice and Florence for a century.

“For the Mamluk [ones], the correct attribution to Egypt and Cairo was more difficult,” he notes.

“Scholars noticed that in western archive documents, several oriental carpets were often called Cairen: Kairene in German, Cairino in Italian, Cagiarino in Venetian. But nobody was able to find out which [ones] they were.”

The key, Boralevi says, remained hidden in the S-shape used for spinning the wool. “This peculiarity, that is found also in other Egyptian weaving, like for instance the Coptic tapestries, led people to think that that group was coming from Egypt,” he says. “[And] it was only in 1983, when I found in Palazzo Pitti in Florence a large Mamluk carpet described since 1570 in the Medici archives as Cairino, that it was possible to associate that term to a specific example.”

Elite trade connection

Despite being traced back to Cairo, many questions still remain about these Mamluk carpets, including where and how exactly they were produced.

Stories suggest that it was the sultan who aspired to develop a cutting-edge industry in Egypt that would command the admiration of the world - and briefly succeeded. Others suggest that, in addition to this, it was the tastes and ambitions of the elites in the Mediterranean basin who inspired the industry.

“There were connections between very elite purchasers of luxury goods and the industry producing them. [Sultan] Qaitbay was aware of it himself, and the people who formed his new carpet industry were aiming for this kind of market,” Rosamond Mack, author of the book Bazaar to Piazza: Islamic Trade and Italian Art, 1300-1600 tells Middle East Eye.

“This was certainly a very sophisticated, ambitious project to hit this market.”

Despite advances in the study of these Mamluk carpets, their emergence and production in Cairo remain largely a mystery. One of the biggest enigmas is that there is no known clear tradition that existed prior to this industry in Egypt - so as far as we know, these exceptional pieces appeared almost out of nowhere.

“Cairo had produced textiles and carpets for a long time, but the quality here was absolutely new and astonishing,” Mack notes.

Scholars note that the technique and design of the carpets suggest that Qaitbay probably relied on the assistance of skilled Turkmen craftsmen who came to Egypt as part of a broader wave of immigrants from northwestern Iran and Central Asia around the time of his reign.

Based on documents in the Vatican Archives that record the carpets commissioned by Pope Innocent VIII, Mack believes that by 1489 there must have been a sufficiently stable and powerful industry in Cairo to take on those gigantic shipments.

“There would have been a well-established [industry]. What they produced was very sophisticated, quite a perfect product,” she says.

'There would have been a well-established industry. What they produced was very sophisticated, quite a perfect product'

- Rosamond Mack, author

However, the exact location where these carpets were woven is still unclear. There are some scholars who speculate that perhaps not all of these pieces were made in Egypt, although there is no solid evidence to support this theory.

“I believe that [the Generalife carpet and the Bardini-Pisa carpet] are court products because of their very refined design, which can be related to the decoration of Qaitbay’s mosque in Cairo,” says Boralevi. “On the other hand, it is possible that other workshops existed, perhaps to produce export carpets. But I don’t have any element to locate them."

The point on which there is instead the greatest consensus is that this industry disappeared following the Ottoman conquest of Egypt in 1517 and the consequent fall of the Mamluks. From that moment on, the Ottoman authorities took the best weavers from Cairo to both Istanbul and Damascus to help develop carpet production there. And although many others remained in the Egyptian capital, their products were never the same again.

Surviving Mamluk carpets

According to Boralevi, the knowledge surrounding antique carpets is built primarily on three elements: direct analysis of the designs, colours and textile structures of surviving pieces; the comparison with examples portrayed in old paintings, and archival research.

“I guess there are nowadays between 100 and 150 surviving pieces, including fragments,” Boralevi says, based on his own estimates. “They are probably a very small percentage of those produced and exported to Europe in the late 15th and 16th century.”

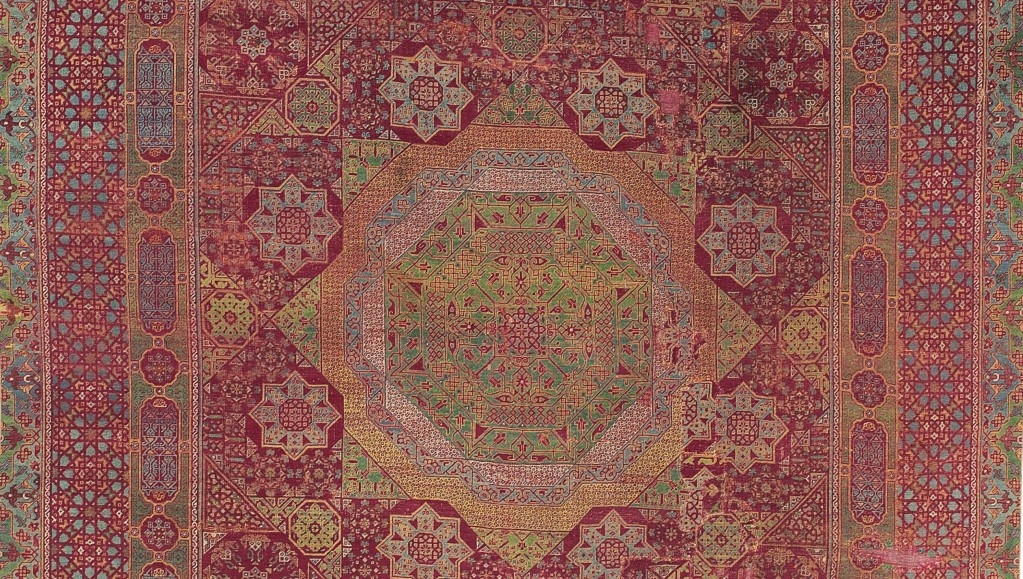

One of the most magnificent pieces that has survived to this day, albeit fragmented, is the carpet of the Generalife, a palace of the Nasrid Sultan of Granada, in Spain, and a venue for dazzling official ceremonies.

This exceptional piece is also one of the largest preserved, and is believed to have been produced in the time of Qaitbay and shortly before the 1492 collapse of what was the last sultanate in Al-Andalus, the Muslim-ruled area of the Iberian Peninsula.

In a detailed description of the piece, Purificacion Marinetto, head of the conservation department at the Alhambra and Generalife Trust in Granada, argues that the carpet must have originally measured just over three metres wide by almost 12 metres long. The proportions of the piece also suggest that it was commissioned directly from Mamluk workshops or was perhaps even a gift between rulers.

“Its decorative typology maintains the tradition of the Mamluk carpets,” Marinetto tells MEE. “I would highlight its existence as a Mamluk luxury object in the Nasrid Granada with a remarkably large size, and perhaps made specifically for the place.

“[These Mamluk carpets] are luxury objects that [were] used as protocol gifts, and in the case of the Nasrid Granada, these were moments of important diplomatic relations.”

Another important example of a splendid Mamluk carpet preserved to this day is the so-called Bardini-Pisa-Cini, whose first known appearance is in a late 19th-century photo of the carpet hanging in the main hall of a gallery in Florence.

Boralevi, who has studied the carpet, claims that it was produced in the fourth quarter of the 15th century, during the reign of Qaitbay. And judging by the fact that it was woven in a single piece, and therefore had to be produced in a well-equipped workshop, he thinks it is likely to have been either commissioned by a wealthy family or a diplomatic gift.

This carpet, rich in Islamic geometric ornaments, has three large medallions in its central part. The biggest one, right in the middle, is a large, eight-pointed star reminiscent of the ceiling of the mosque and mausoleum of Qaitbay in Cairo.

Other pieces that we only know about thanks to archival research are the Mamluk carpets of Pope Innocent VIII (1484-1492). Thanks to two documents in the Vatican Archives, largely ignored for a long time, Mack discovered that in 1489 the Pope had bought seven carpets “of large dimension” that were produced and shipped from Cairo.

The documents do not mention where the carpets - five of which are described in a 1518 inventory as “huge Damascene floor carpets”- were placed. But considering the measures, Mack believes that there are only three options: two in the former Apostolic Palace, between the Sistine Chapel and the Papal Palace, and one in a room in the east wing of the papal residence, where the throne often rested.

“The Pope Innocent VIII record of the purchase is made in a very unusual way, which shows his personal intervention,” Mack says. “I think he was very conscious of acquiring these carpets and he wanted to ensure that in the records this was not registered as gifts but as his own purchases.”

Evidence trail in art

In the arts world, one of the earliest reproductions of a Mamluk carpet is depicted in Paris Bordon’s canvas The Presentation of the Ring to the Doge, which was part of the decoration of a hall in the Scuola Grande di San Marco, an iconic building in Venice.

The painting, completed in 1534 and now displayed in the Accademia Gallery in Venice, shows the final part of a miraculous event that took place in 1341: an old fisherman hands the doge - the head of state in several Italian city-states in the medieval and Renaissance eras - the ring given to him by Saint Mark, who appeared to him during a sea storm.

The scene is set in a monumental loggia reminiscent of the Palazzo Ducale in Venice. And in the central part of the canvas, at the doge’s feet, lay two carpets: one is of Ottoman style, while the other is Mamluk, Mack argues.

It is also very likely that people came to know these splendid carpets at the eastern end of the Mediterranean basin, in Palestine; in particular, in the majestic Madrasa al-Ashrafiyya in Jerusalem, on the western side of Al-Haram al-Sharif.

The madrasa was initially commissioned by a predecessor of Qaitbay. But when he came to power and visited the site in 1475, he didn’t like it, and ordered its reconstruction. It was the new madrasa, built in the Cairene style, that was famously described by a Palestinian judge and historian, Mujir al-Din, as the third jewel of Al-Haram al-Sharif, after the Dome of the Rock and al-Aqsa Mosque.

In his detailed description of the site, Mack notes, Din did not miss the carpets, which he described as of “unsurpassed beauty, the like of which is not found elsewhere”, a reference she believes makes it very likely that the carpets were also produced in Cairo.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].