Osman Hamdi Bey: Artist, archaeologist and protector of Ottoman heritage

Though accomplished as a painter, looking back on Osman Hamdi Bey as just an artist would be to hugely underappreciate his remarkable achievements in other fields.

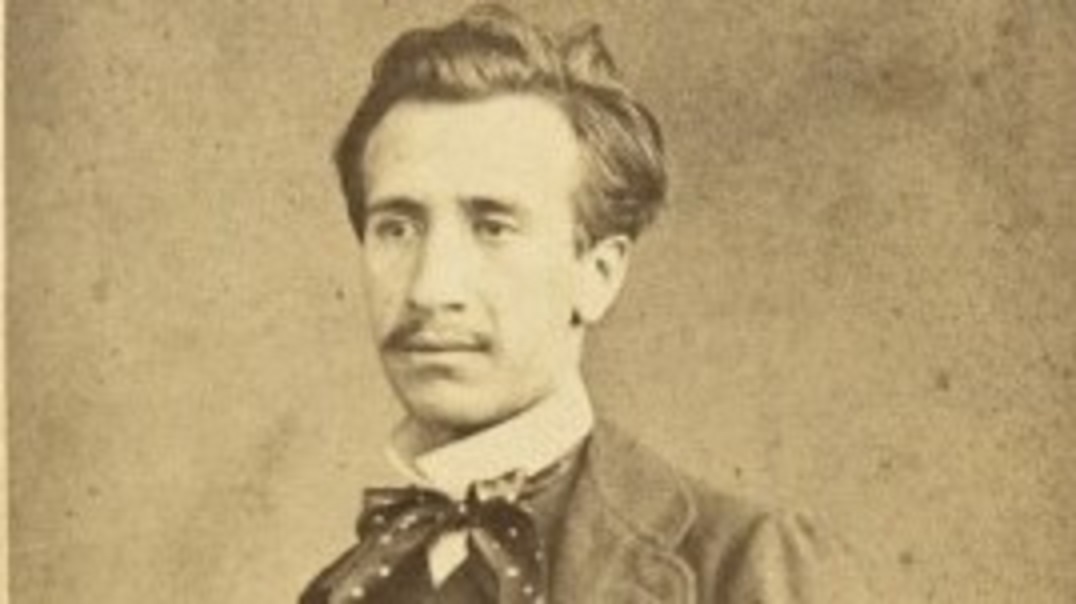

Born in 1842 to the Ottoman intellectual and eventual grand vizier, Ibrahim Edhem Pasha, Hamdi Bey was a key figure in redefining Ottoman art and establishing many of the empire’s cultural institutions.

As an artist and archaeologist, he came to embody Western art’s penetration into elite Ottoman life while simultaneously protecting its myriad historical treasures from looting by western adventurers.

A name little-known outside of Turkey and high art circles, Hamdi Bey holds the distinction of producing the most expensive painting by a Turkish artist ever sold.

His 1880 painting Girl Reciting the Quran sold for $7.7m at auction in 2019 breaking the previous record, also held by Hamdi Bey, for the painting In Front of the Mosque, which sold for $4.5m in 2016.

His most famous painting, The Tortoise Trainer, sold for $3.5m in 2004.

But to consider Hamdi Bey and his artworks a product exclusively of his Ottoman homeland is a mistake.

The artist lived amid the synthesis of European and Islamic culture that emerged among Ottoman elites during the 19th century.

Like most of his contemporaries and his father before him, Hamdi Bey was sent to Paris for his education, initially studying law before deciding to pursue the arts.

The experience in Europe was to have a big impact on the young Ottoman’s life.

In France, he met his first wife Marie and studied under Orientalist artists, such as Jean-Leon Gerome and Gustave Boulanger.

The former produced perhaps one of the most infamous works in the Orientalist tradition.

Gerome’s The Slave Market depicts men in eastern robes and turbans inspecting a naked young woman for sale. The image reinforces stereotypes of Muslims as cruel and carnally driven, and it was given a new lease of life by the far-right Alternative for Germany party in 2019 in a poster campaign warning against Muslim migration to Europe.

The Orientalist influence on Hamdi Bey’s works is clear, evident in the exoticised choice of clothing for most of his subjects and his tendency to make similar stylistic choices to others within the tradition. Nevertheless, the Turkish artist casts his scenes in a manner more sympathetic than his mentors.

Hamdi Bey’s subjects read the Quran, train tortoises, socialise outside mosques, and haggle over Persian carpets.

While his scenes might take place within an artistic framework established by Western predecessors, Hamdi Bey’s subjects in some instances turn their gazes back on the West.

Notable in this regard is Persian Carpet Dealer on the Street, where a green-robed Muslim man fixes his eye with curiosity towards a Western visitor busy in negotiations over a purchase.

The painting may serve as a summary of Hamdi Bey himself, someone intrigued by the advance of Western ideas but still very much at home within his Muslim homeland.

Preserving Ottoman heritage

But as significant as Hamdi Bey’s art is, his paintings merely punctuated a career largely dedicated to the discovery and preservation of the heritage of Ottoman-ruled lands.

The Ottoman intellectual left Europe in 1869 and became the director of the Provincial Foreign Affairs Department in Baghdad.

It was here that he first articulated his intent and motivations, namely to play a role in advancing the culture and civilisation of Muslim peoples.

In his letters to his father, penned in French rather than Turkish, he complained about the supposed backwardness of the Muslim world and called for reforms to catch up with Europeans when it came to the sciences, administration, art, and other fields.

“The merchants are not honest at all,” he remarked on his experiences in Iraq.

“If they were in France, they would be sentenced to hard labour immediately,” he adds, explaining that the elites within the monied and political classes were deliberately keeping ordinary people in poverty and ignorance.

Hamdi Bey returned to Istanbul from Baghdad in 1871, serving in a number of official capacities, including as mayor of the Beyoglu district of Istanbul.

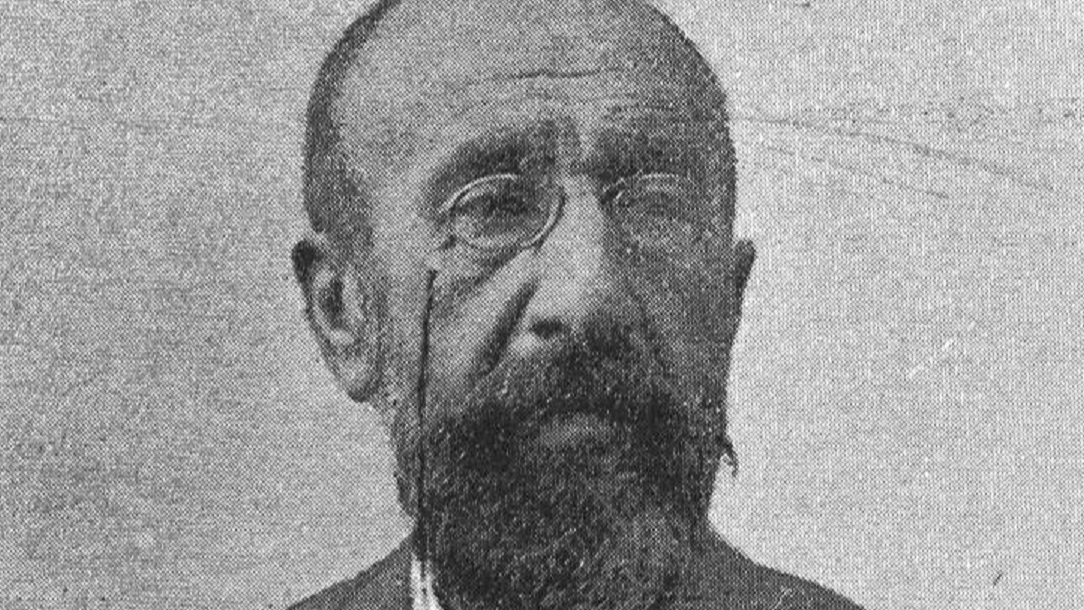

The year 1881 marked a turning point in his life when he became the director of the Imperial Museum (Muze-i Humayun), succeeding the Englishman Edward Goold and the German Philipp Anton Dethier, the first two directors of the museum.

Hamdi Bey was the first Turk to take up the position. Until his appointment, both Ottoman officials and citizens had paid little attention to their territory’s rich heritage.

This mode of thinking had allowed Europeans to rummage through the empire, helping themselves to artefacts that local officials either had relatively little regard for or whose value they were not aware of.

That was a mindset Hamdi Bey was determined to change and he set about implementing ways of recording his homeland’s archaeological treasures.

He began by classifying and cataloguing new finds, as well as creating an inventory of the museum’s existing collections and deciding on which would be exhibited.

The artist and statesman put into effect what was essentially a nationalisation of archaeological activity in the Ottoman empire.

Most notable was his lobbying for new legislation on the preservation of historic artefacts, which prevented local Ottoman governors and even the sultan himself from sending objects abroad as gifts.

This law was so meticulous in its detail that it remained in effect deep into Turkey's Republican era and it wasn't replaced by an updated code until 1973.

Also in 1881, the artist, working closely with the architect Alexander Vallaury, commissioned the construction of the main building of the Istanbul Archaeology Museums complex, cementing its status as the Ottoman Empire’s main museum complex on its opening in 1891. Its main building was followed by the construction of two other buildings in 1903 and 1908.

The institution was the first established by Ottoman citizens and was comparable to those found in other European cities.

'A first in Turkey’s history, Osman Hamdi Bey created a museum catalogue with amazing photographs'

- Emir Son, archaeologist

Emir Son, an archaeologist at the museum, told Middle East Eye that before Hamdi Bey became involved his predecessors had simply collected and piled up objects.

“A first in Turkey’s history, Osman Hamdi Bey created a museum catalogue with amazing photographs,” Son said.

“When introducing the objects, you need to have information about them. To this end, he [Hamdi Bey] created a huge library within the museum, consisting of books about archaeology and art.”

Hamdi Bey also established the School of Fine Arts (Sanayi-I Nefise Mektebi) in Istanbul in 1882, which would later change its name to Mimar Sinan University, which remains the country’s top institution for the study of the arts to this day.

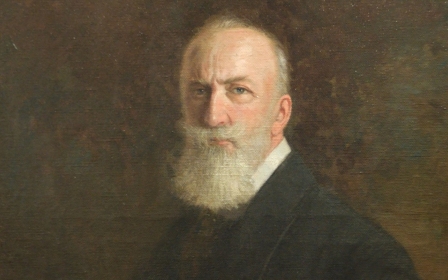

Before his death in 1910, Hamdi Bey had essentially given birth to modern Turkey’s artistic establishment, ensuring that Turks would be responsible for their own heritage for decades to come.

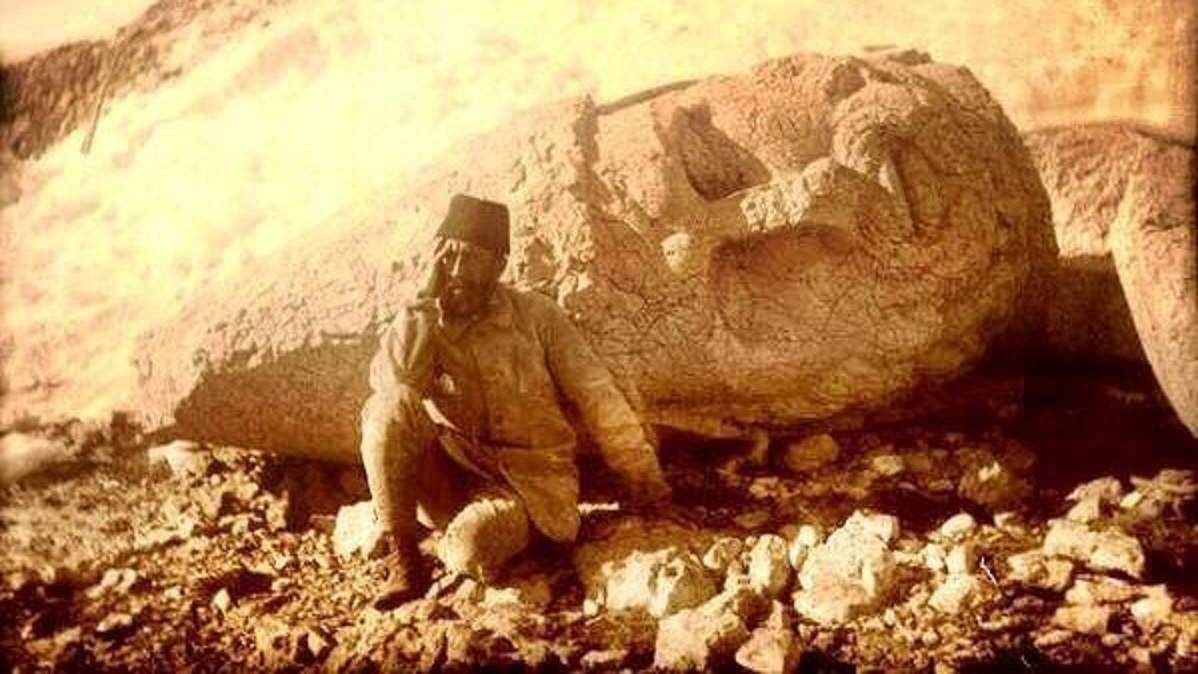

Sidon excavations

Despite his elite upbringing and senior position within the Ottoman bureaucracy, Hamdi Bey was not afraid to get his hands dirty.

Between 1883 and 1895, he led an array of archaeological excavations throughout the empire, not just within the borders of contemporary Turkey but also in what are today Arab states, such as Syria and Lebanon.

Those expeditions unearthed significant ruins and troves of artefacts, including sarcophagi, columns, and statues at sites including Palmyra and Kadesh in Syria, and around the Aegean Coast in Anatolia.

His most notable discovery was in rural Sidon in Lebanon in 1887, where a villager had stumbled across ancient ruins while constructing a new house.

In line with the legislation Hamdi Bey had prepared, the villager informed the local Ottoman governor, who examined the site himself and relayed the findings to his superiors until the news had reached Istanbul.

There, the Ottoman Sultan Abdulhamid II tasked Hamdi Bey with leading the excavations and bringing the objects back to Istanbul, a project that would last for three months in its initial stage.

Hamdi Bey led a team of researchers who uncovered a royal necropolis packed with sarcophagi, which dated back at least 2,400 years.

Most important among them was the fourth century BCE Alexander Sarcophagus; a remarkably well-preserved artefact weighing 15 tonnes and standing more than three metres tall.

The sarcophagus was decorated with detailed reliefs depicting Alexander the Great in historic and mythological battle scenes, including his defeat of the Persians.

Early analysis dashed the hope that the tomb housed the great conqueror himself but instead it was found to belong to Abdalonumus, who was appointed King of Sidon by Alexander in 332 BCE.

Another well-preserved find from the excavation was the Sarcophagus of the Crying Women, which like the Alexander Sarcophagus continues to be on display in Istanbul to this day.

'Concern'

Hamdi Bey’s excavations did not go unnoticed by Western archaeologists who became concerned by the Ottoman’s success, perhaps driven by a mixture of professional rivalry, cultural prejudice, and the loss of an opportunity to acquire precious artefacts for their own countries.

Not long after the excavation in Sidon began, one British newspaper expressed fear that Osman Hamdi Bey and his team, consisting mostly of Muslims, would fail to carry out such an important project properly.

The British missionary William Wright, who worked around Damascus in the late 19th century, sent a letter to The Times newspaper, imploring the British Museum to intervene and claiming that “vandal Turks [Muslims] would break, destroy, or sell the pieces.”

The newspaper changed its tone when confronted with evidence of Hamdi Bey’s successful excavation and later referred to the Ottoman as “his excellency”.

For Turks, Hamdi Bey’s vindication is a matter of national pride.

“He constructed a new port in Sidon just for loading [the artefacts],” says Istanbul Archaeological Museums’ Emir Son, further describing the project as a “tremendous effort”.

“There are 50 people working in this museum,” he continues. “This museum has around one million objects. We proudly exhibit the Alexander Sarcophagus.

"We owe all of this to Osman Hamdi Bey."

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].