Hajj: How a new Saudi-run travel agency failed western 'guests of God'

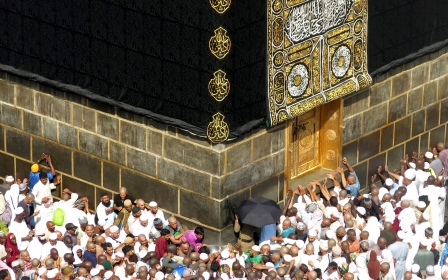

Up to one million vaccinated Muslims under the age of 65 are arriving in Mecca from across the globe ahead of a much-anticipated, first large-scale Hajj since the Covid-19 pandemic began.

Hajj is one of the five “pillars”, or religious duties, of Islam, and all physically and economically able Muslims are required to perform it once in their lifetime.

However, just a week or so before the annual pilgrimage is due to commence on 7 July, a new Ministry of Hajj-accredited online travel agency is failing intending pilgrims among more than 30 million Muslims in Europe, the Americas and Australia.

While many are still uncertain about whether or not they will be able to travel in 2022, some who have paid in full already seem likely to miss out completely.

The Saudi Ministry of Hajj announced a last-minute decision on 6 June that all potential pilgrims from the West must apply through a new platform, Motawif. It takes its name from the hereditary guilds that have enjoyed the exclusive right to serve pilgrims in Mecca for centuries.

Overnight, the portal became the only place to buy accredited Hajj packages across 57 western countries, subjecting Muslims there to an e-draw for the very first time, necessitated by ongoing Covid-related restrictions on pilgrim numbers.

Hajj lotteries are commonplace in Muslim-majority states where national quotas of just 1,000 pilgrims per million people are in operation. While many wait years to perform their pilgrimage, western Muslims have never been subject to such draws. For decades, they were not restricted to the same quotas as the Islamic world and have performed Hajj more or less on demand.

Reduced Hajj numbers

Hajj is one of the largest annual gatherings of humankind. During the 2010s between 1.9 to 3.2 million visiting pilgrims generated more than $8bn in yearly revenue for Saudi Arabia. However, Covid-related measures during 2020 and 2021 meant that pilgrim numbers were radically reduced by the Saudi government to just 1,000 and 60,000 vaccinated visitors, respectively.

The number of spaces allotted to western countries has steadily decreased since April

On 9 April, the limit for 2022 was raised to one million, a 55 percent reduction on normal national quotas but still a first step towards restoring Hajj to its pre-pandemic scale. The journeys of most of the 850,000 expected international pilgrims are still being coordinated through established channels such as government missions and private companies in Muslim-majority countries.

Pilgrims already living in Saudi Arabia were also directed to register for an e-draw. When the 150,000 spots reserved for domestic pilgrims were not filled immediately, the Ministry of Hajj reduced prices for its packages.

Moreover, the number of spaces allotted to western countries has steadily decreased since April. No transparent explanation was given but it is broadly in line with the 1,000 pilgrims per million people rule.

For example, on 13 June, the British Consulate General in Jeddah informed a meeting of the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Hajj & Umrah that the UK's allocated number of 12,000 pilgrims would be reduced to only around 3,000.

Though pent-up demand from pilgrims was at least expected to be high, the lower figure likely reflects the lack of capacity to deliver entirely new systems on short notice, whether online or on the ground.

Modernising religious tourism

Since the 1990s, religious tourism has been viewed by Saudi Arabia as a key means of diversifying its non-oil-based economy. In 2016, the kingdom’s plan for future modernisation, Vision 2030, set ambitious targets to more than double pre-pandemic Hajj pilgrim numbers to six million and grow the much shorter, year-round Umrah pilgrimage to 30 million by 2030.

A radically simplified online system for buying and selling Hajj packages direct from Saudi Arabia is a part of this strategy. In a government increasingly centralising power, there is an eagerness for greater control and rapid modernisation of the traditionally independent and lucrative but slower-moving Motawif companies.

The application of technology is viewed by the Saudi government as key to meeting market-based and operational challenges. Amid very recent changes to its senior leadership, successful operation of the new portal can therefore be viewed as a government test for Motawif's operator.

For 40 years, the primary function of Motawifs was to deliver transportation, tents, and other services to overseas companies organising Hajj on behalf of western Muslims. However, until now this company was not responsible for other key elements of Hajj packages including their systems and logistics.

So, in practice, Motawif is new to this aspect of the business. Running the operation is a Dubai-based subsidiary of the Indian tech company, Traveazy, with experience of selling the much simpler, less complicated Umrah pilgrimage online.

Replacing the 'middleman'?

It was only in 2006 that pilgrims living outside of Muslim-majority countries were first required to purchase a Hajj package - including a visa, flight, accommodation, and other Hajj services - from one of hundreds of ministry-licensed munazzams (organisers) in their home countries. By 2019, for instance, there were 117 munazzams in the UK, by far the largest number in the West.

While Motawif is backed by the financial might of the Saudis, it is not clear what consumer protection their packages will provide when things go wrong

During the last two decades Hajj services operated as “B2B” (business to business) with munazzams mediating between the Motawif and their own smaller groups of 150-450 pilgrims. The best of these organisers have vital local knowledge both of their own specific customers’ diverse cultural, religious and linguistic needs and the particularities of the Saudi setting.

But, hundreds of munazzams employing thousands of people across three continents will play no formal part in the Hajj of 2022 and are facing up to probable future redundancy.

On 10 March these companies were prompted by the Ministry of Hajj to update their details on the existing E-Hajj system. Ministry of Health circulars on health were issued on 21 April. So, until May, there was no suggestion that the pilgrimage business would proceed any differently from before the pandemic.

Many munazzams began to advertise Hajj packages for 2022 but, while some eventually had their licenses activated, these were revoked within hours. Then rumours of the imminent launch of an online travel agency prompted munazzams from Europe and the US to travel to Saudi Arabia. Yet, suggestions of various models for a transitional, hybrid system based on continuing cooperation were rejected; Longstanding bonds held by the Saudi authorities have still not been returned.

Meanwhile, in the absence of munazzams and their teams, it is unclear, too, how Hajj groups are being constituted and whether Motawif employees will have the experience and know-how to deal with challenges ranging from carefully allocating hotel rooms if strangers are required to share, to sensitively offering religious advice to Muslims who follow quite different traditions.

Protecting western pilgrims

Certainly, the munazzam system had its problems. Due to discrepancies across Saudi and western licensing and regulatory frameworks, a significant number of munazzams sold on their allocations to sub-agents who were free to configure, advertise and take payment for Hajj packages in long chains of buying, selling and touting. This meant that some pilgrims did not get what they were promised or paid for.

However, while Motawif is backed by the financial might of the Saudis, it is not clear what consumer protection their packages will provide when things go wrong – as they have done already - and whether they will compare favourably to national schemes such as the UK's Air Travel Organiser’s Licence or the EU Package Travel Regulations.

In Europe, these frameworks protect pilgrims if munazzams go out of business. Any pilgrims that paid deposits to them - including a good proportion of the tens of thousands from the West whose Hajj trips were cancelled due to the 2020 Covid outbreak - were advised by the Saudis to seek a refund.

However, while trade associations like the UK's Licensed Hajj Organisers have instructed their members to comply - and advised customers to report them to local UK trading standards departments if they do not - cash-flow is currently a problem for these narrowly specialised businesses. They themselves still have tens of millions of pounds in paid deposits to Saudi Arabia without a straightforward means of releasing it.

To be sure, selling Hajj packages directly to customers online could, in theory, put an end to offline "mis-selling". But, unfortunately, registration on the Motawif portal in early June prompted email “spam”, raising questions about the security and selling of pilgrims’ data, while “spoof” emails from hackers were reported too.

Rising costs

Alongside potential fraud, the rising costs of Hajj have been a perennial concern for pilgrims. Suspicious that local organisers have been profiteering for years, prospective pilgrims were buoyed by Motawif's initial claim that "[its] package rates are on average 35 percent lower than the market rates".

Indicative package previews launched on 10 June did initially look competitive. Indeed, some suggest that the Ministry of Hajj asked Motawif to review its initial pricing before going to market. In the UK, prices were advertised as from "£6,193 (Silver)" to "£9,652 (Platinum)" per person.

Given the timescales and what has become a chaotic roll-out process, many pilgrims have not felt confident enough to travel this year

Yet, packages advertised under the munazzam and Motawif systems cannot easily be compared like for like.

Perhaps because other deals had not yet been struck with up-scale hotels, the Motawif's preview package accommodation was one mile from the Great Mosque of Mecca. Thus, it was always likely to be cheaper than the most reputable hotels overlooking the sanctuary which are attractive to many western pilgrims.

Packages for Ireland, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand did not include flights because only those offered by Saudi Arabia’s national carrier, Saudia, are included. Arranging flights independently from these countries has proved to be prohibitively expensive or otherwise difficult.

Remarkably, some "decision pending" pilgrims are still unsure about whether they have been successful or not in the e-draw. Those "approved" subsequently discovered that not all packages, originally selected at application, have remained available to book. Some paid successfully for a package only after endless credit-card rejections, while others received "booking failure" messages that in many cases are still unresolved.

The price, configuration and/or itinerary of what could be purchased also continued to change and could not be always tailored to individual needs such as previously booked annual leave, childcare arrangements, and so on.

Given the timescales and what has become a chaotic roll-out process, many pilgrims have not felt confident enough to travel this year. Others have felt compelled, for religious and other reasons, to make sub-optimal choices in haste only to discover hours or days later that new packages at new prices were still being released.

In the UK, packages departing London or Manchester for a twin-centre stay in Mecca and Medina offered mainly five-star accommodation for between 19-23 days (with nothing shorter) in the price range of £6,434 - £14,926 per person.

Payment is in Saudi riyals, so exchange rates fluctuate and sizeable charges for foreign currency transactions have applied too. Final package prices seem no cheaper than those of the munazzams who have long since argued that the rising cost of Hajj can be explained by seasonal supply and demand for flights and accommodation in international hotel chains, as well as new Saudi taxes and the commercialisation of Hajj services per se.

Indeed, as Motawif now has a monopoly in the western Hajj marketplace, it would be consistent with the goals of Vision 2030 for its operators to maximise profits for the Saudi economy, depending, that is, on what is being paid to its overseas tech partner.

A distressing experiment

At its launch, Motawif suggested that its business to consumer (B2C) digital marketing model would benefit western pilgrims as a “quick and easy” way of booking their travel. However, the system was not fit for purpose evidenced by slipping and changing timelines. Numerous technical glitches and other failures suggest that its only “piloting” has been on unwitting pilgrims across the West over the last few weeks.

Sincere yet savvy pilgrim-consumers resent being treated as mere 'guinea pigs' for a system that could eventually be rolled-out worldwide

Even as the first Saudia Hajj flights departed the UK over the weekend, members of swiftly formed WhatsApp and Telegram groups including munazzams and pilgrims welfare associations, were tirelessly organising to disseminate their know-how, advising on desperate visits to embassies to address visa queries and liaising directly with airlines to secure unsent tickets.

Even so, some Hajjis have been turned away at the airport because Motawif has overbooked flights or not yet paid.

Through all of this, western pilgrims have been met mainly with silence or belated, generic, and contradictory communications from the Motawif team. The rhetoric of customer care - for no less than the “Guests of God” - is being tested as never before. Sincere yet savvy pilgrim-consumers, who have a profound desire to perform their religious duties, resent being treated as mere "guinea pigs" for a system that could eventually be rolled-out worldwide.

It is still unknown how many pilgrims from Europe, the Americas and Australia applied for Motawif packages and how many will perform Hajj in 2022. Sources close to the Saudi authorities claim 100,000 - perhaps including applications for multiple packages - while sceptics suggest the final numbers of Hujjaj from these countries will be less than 10,000 in total.

In any case, it will be interesting to follow reports of pilgrims' experiences on the ground during Hajj and, ultimately, to see whether and to what extent the bitter feedback of 2022 registers in an environment that even before Motawif’s launch has long since struggled to provide reliable, transparent information for pilgrims.

In time, perhaps the personal guidance, flexibility and consumer protection offered by the best examples of the munazzam system will be (re)incorporated, replicated or bettered.

For more information, please read the full report on Mapping the UK's Hajj sector.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].