Boris Johnson and the Middle East: Gaffes, talking Turkey and pro-Israel pressure

After just under three years in office and following a slew of scandals and resignations, British Prime Minister Boris Johnson on Thursday finally announced he was going to resign.

During his tenure he has overseen some of the biggest crises to face the country in recent years: primarily the Covid-19 pandemic and the process of removing the UK from the European Union.

In foreign policy terms, he has made much of his involvement in the war in Ukraine and his support for resistance to Russia's invasion.

But in the Middle East, Johnson's legacy is a mixed. Having taken up the premiership following two years as foreign secretary, he largely bolstered the UK's traditional relationships in the region, but his career has also been marked by what have been seen as a number of unforced errors.

With Boris Johnson's days in Downing Street now numbered, Middle East Eye takes a look at some of his most notorious Middle East-related moments.

1. The fate of Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe

Boris Johnson's involvement with the Middle East is likely to be defined - in the minds of most British people - by the Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe affair.

British-Iranian aid worker Zaghari-Ratcliffe was arrested in Iran in 2016 while on holiday with her family, accused of conspiring to otherthrow the Tehran government and sentenced to five years in jail.

Her imprisonment, which was later extended, became a highly publicised running scandal in the UK until she was finally released in March 2022 and returned to Britain.

While foreign secretary, Boris Johnson was heavily criticised when, in 2017, he claimed at a meeting of the Foreign Affairs Select Committee that Zaghari-Ratcliffe had been "teaching people journalism" in Iran.

His comments, which he admitted later were a "mistake", led to the Iranian-British citizen being brought before a court once more and accused of "spreading propaganda against the regime".

The threat that her sentence would be extended hung over her, though in the end no extra charges were brought.

It is generally accepted that Zaghari-Ratcliffe was used as a bargaining tool by Tehran to force the UK government to pay a £600m ($719m) debt owed to Iran over an order of armoured vehicles that was cancelled following the 1979 Islamic Revolution.

On 16 March 2022, Boris Johnson's government announced it had paid the debt owed to Iran and on that same day Zaghari-Ratcliffe returned to the UK.

Upon returning she was highly critical of Johnson's handling of the affair.

"I don't agree with Richard [her husband] on thanking the foreign secretary, because I have seen five foreign secretaries over the course of the six years… how many foreign secretaries does it take for someone to come home, five?" she said.

“I think the answer is clear. I cannot be happier than this that I’m here. But also, this should have happened six years ago.”

2. Talking Turkey

Boris Johnson has regularly made reference to his Turkish heritage. His great-grandfather, Ali Kemal, was a liberal reformer turned unpopular and short-lived interior minister for the Ottoman Empire.

Kemal was murdered during the Turkish War of Independence and in practice, his great-grandson's relationship with Turkey has often been fairly bumpy.

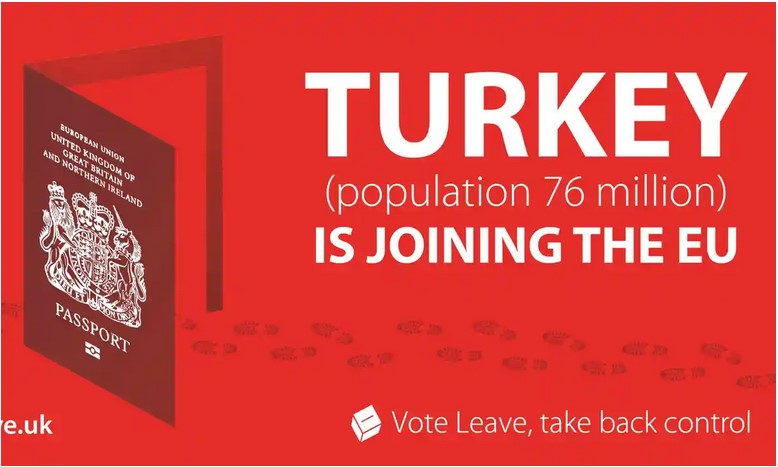

In 2016, as a leader of the campaign to leave the European Union, the spectre of Turkey joining the EU and millions of Turks having access to freedom of movement was a regularly touted scare story that may have helped swing the vote.

That same year, Johnson won a competition in the Spectator magazine for an offensive poem about Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, in which he described him as a "wankerer from Ankara" and implied he had sex with goats.

Later, he was able to put relations back on a more steady footing, not least as both countries' relations with their neighbours in the EU began to deteriorate.

According to a report by MEE in 2018, the UK sold Turkey more than $1bn worth of weapons after the poem incident, while both countries have been heavily reliant on one another for trade and tourism.

In one of his last foreign engagements before resigning, Johnson met with Erdogan at a Nato summit.

A video released from the summit shows Erdogan jokingly addressing Johnson and saying "this one is a disgrace to us", apparently in reference to his Turkish heritage. Johnson responds with "very nice, very nice" in Turkish.

3. Rwanda and the refugee 'crisis'

For many years, there has been discussion in the British media and political class about how to deal with people seeking refuge in the UK by crossing the English Channel from France.

As someone who came to power partly on the basis of xeonophobic rhetoric linked to the anti-EU campaign, Johnson has tried to make much political capital out of the issue.

In 2022, Johnson's government unveiled its plan: asylum seekers arriving through "illegal" means would be put on a one-way charter plane to Rwanda, where they would expected to seek asylum.

The policy horrified human rights campaigners and has, so far, been blocked by court appeals, including one to the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR).

While Johnson has claimed the policy is aimed at deterring people smugglers, others claim its sole purpose is to dissuade refugees from attempting to come to the UK.

Those who made the crossing to the UK - many Syrians, Iraqis and Iranians - and who are still being held in detention and threatened with transport to Rwanda, were dismayed at their treatment in what they thought was a welcoming country.

"If I knew there was such a policy, I wouldn't come to UK," one Iranian Kurdish refugee told MEE last month.

"At the same time, I wouldn't be staying in Iran... my life would be worse there."

4. Clampdown on Palestinian movements

In their resignation letters, Tory ministers have made much of Johnson's "success" in seeing off then Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn at the 2019 general election.

Corbyn's reputation as a staunch supporter of the Palestinians and a long-running crisis over allegations of antisemitism in the party have provided ample opportunities for Johnson's government to show its pro-Israel credentials.

In November 2021, Johnson's government announced that it would be listing the Palestinian organisation Hamas as a terrorist group in its entirety in the UK, having previously only done so for its military wing.

The new law meant that "members of Hamas or those who invite support for the group could be jailed for up to 14 years", with Home Secretary Priti Patel saying it was crucial for fighting antisemitism in the UK.

Another piece of legislation promised by Johnson - though not yet actually implemented - is a ban on the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movement that aims to apply non-violent pressure on Israel to follow its obligations in international law.

The new policy was promised in the Queen's Speech in May and has been criticised as an "attack on democracy" by pro-Palestinian campaigners.

5. The Gulf states and the Yemen war

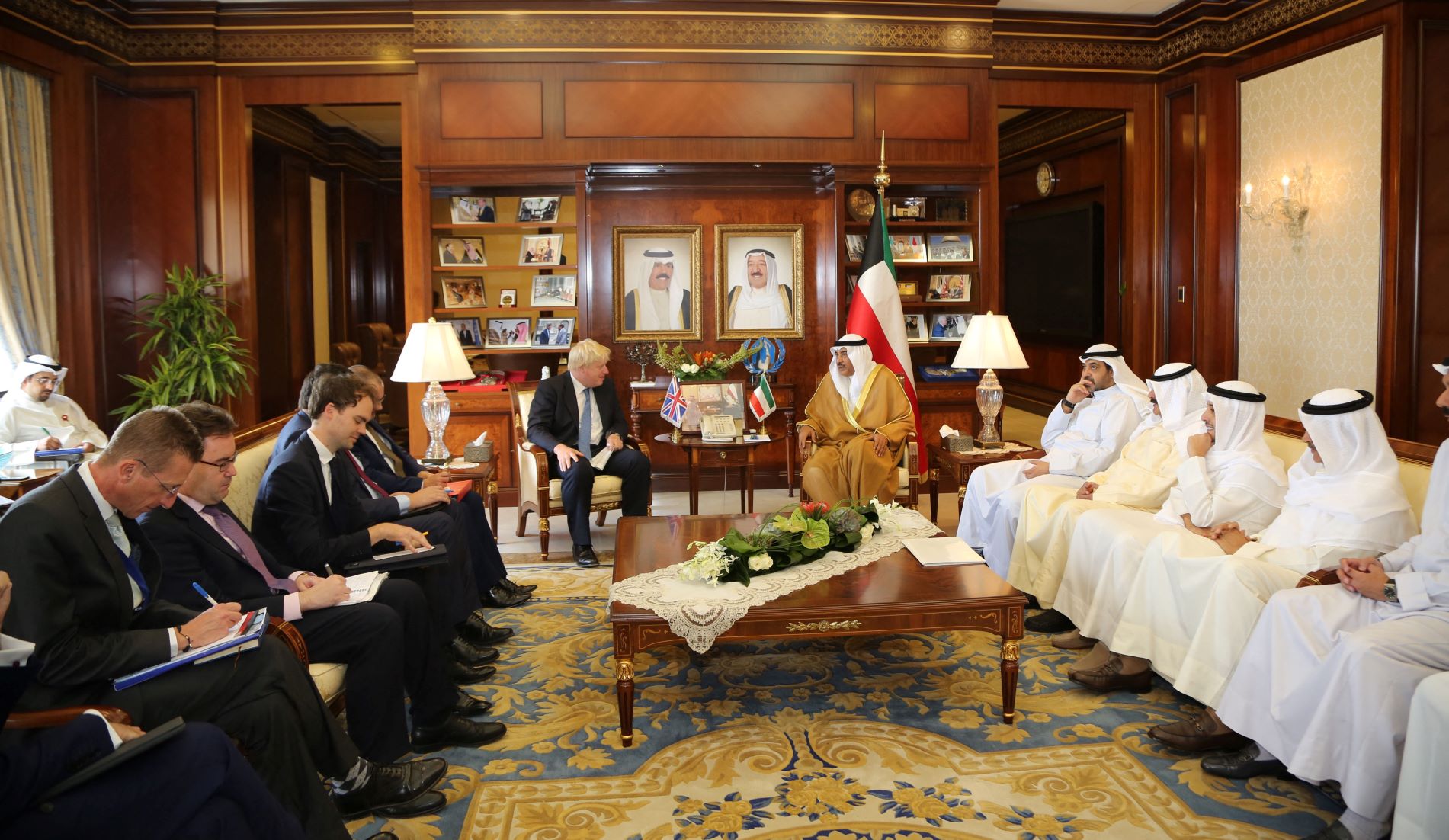

As both foreign secretary and prime minister, Johnson has largely maintained the UK's traditional relationships with the Gulf states.

During the 2017 boycott of Qatar by its neighbours, Johnson - while stressing that the country should tackle "extremists" - called for the boycott to end and later attempted to mediate between the different sides.

His cordial relations with the Gulf states have come in for criticism from human rights groups, particularly over his government's continuing support for the Saudi-led coalition's war in Yemen.

Billions of pounds worth of equipment was reportedly sold to the coalition by the UK, even as the war turned Yemen into what the UN has described as the world's worst humanitarian disaster.

A temporary halt was placed on the UK's arms sales to the coalition in 2019 after the Court of Appeal ruled there had not been adequate assessment of the risks to civilians from the sales - but less than a year later sales resumed after it was deemed that only "isolated incidents" of civilian deaths had occured.

In what was Johnson's last trip to the region prior to announcing his resignation, he touched down in Saudi Arabia on the same day that the kingdom executed more than 80 prisoners.

“It is not acceptable to cite Russia’s war crimes to try to justify trading blood for oil elsewhere," said Reprieve director Maya Foa, at the time.

"It shows the world we will apply double standards for our convenience and embolden countries like Saudi Arabia into further atrocities, just as Putin was emboldened by our willingness to take his cronies' cash for decades."

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].