Tunisia draft constitution: A recipe for more turmoil

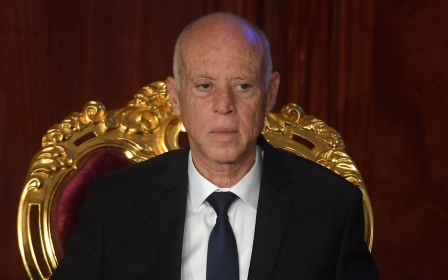

On Monday, Tunisians will vote in a national referendum on a draft constitution that would give the president, Kais Saied, unchecked powers.

Last month, the draft of Tunisia’s new constitution was released amid severe economic and political crises in the country that undermine its legitimacy.

The draft swiftly raised an outcry among elites, who criticised its attempt to establish a super-presidential regime, with powers concentrated in the hands of one man, Saied, without any institutional checks and balances.

Neither the draft, nor the president himself, have addressed the question: What would happen if the project is rejected in the upcoming referendum?

Days later, Saied issued a revised draft to “correct errors” in the original.

While the amended text is somewhat improved, including through a softening of the language around restrictions on rights and freedoms, the substance is largely the same, codifying one-man rule.

The preamble evokes the constitution of 1861, a text established by the bey during Tunisia's first period of constitutional monarchy, but not those of 1959 or 2014, which came after popular struggles. It chooses to start with “We the Tunisian people” (rather than referencing “the representatives of the Tunisian people”), and ends with the slogan “the people want”.

The new draft upholds the symbolic nature of the president as not simply representing “the people”, but actually embodying them.

Significant risk

The Tunisian presidency also recently published a statement that focused on righting the path of history, taking revenge against the corrupt who have stripped wealth from the people - further drawing from the populist repertoire.

Sadok Belaid, the head of the constitutional drafting committee, has disavowed the proposed draft, which has reignited questions and controversy over the relationship between Islam and constitutionalism.

The new draft states: “Tunisia is part of the Islamic Ummah [worldwide community], and only the state shall work to implement the Maqasid [principles of sharia] of Islam in preserving life, honour, money, religion and freedom.”

The words “under a democratic system” were added to the revised version of the draft. This formulation was unexpected, as Belaid had previously announced that references to Islam would be removed from the constitution.

But while the introduction of sharia as a basis for government and legislation comes with significant risks, this should not divert attention from more important changes to the country’s political regime.

Key details missing

The draft constitution would enable an omnipotent and unaccountable president, while also weakening the judiciary and constraining other branches of the state. It allows the president to serve two five-year terms, which could be extended in the event of an undefined “imminent danger”.

In addition, the creation of a new institution called the “Assembly of Regions and Districts” appears to have been done in haste, without attention to detail, as the text does not clearly specify its prerogatives or its relationship with the Assembly of the People’s Representatives.

Such uncertainty is exacerbated by the fact that seven months after the announcement late last year of a road map for parliamentary elections on 17 December, there has been no decree to officially set this date.

Nor does the draft constitution include a date for elections, stating only that the provisions of presidential decree 117, issued last year to suspend parliament and give Saied exceptional powers, would continue to apply until an election is organised. That paves the way for the current state of exception to continue indefinitely.

The draft also introduces measures allowing for the recall of political representatives, which in a context of heightened societal and political tensions, could morph into a tool for revenge or blackmail.

Meanwhile, the country’s highest judicial body, the Supreme Judicial Council, has been fragmented and the Constitutional Court weakened considerably, with the president proposing to limit its members to judges he appoints directly.

Neither the draft constitution, nor the president himself, have addressed the question: what would happen if the project is rejected in the upcoming referendum?

Several hypotheses exist, including an interim presidency by Prime Minister Najla Bouden and early presidential elections, or a new referendum on a draft approved by Belaid.

At the same time, prominent groups such as the Tunisian Human Rights League and the National Syndicate of Tunisian Journalists are mobilising against the project, which is widely viewed as a major assault on civil and political rights.

The views expressed in this article belong to the authors and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].