Ghassan Kanafani, Zionism and race: What determines the fate of a people

One of the strangest ironies in Zionist ideology is its reliance on the concept of biology and race to define who is a Jew, the very same concepts which 19th century Europe invented and weaponised against European Jews.

Zionists deployed an antisemitic claim to argue that modern European Jews are somehow rooted in Palestine in order to render them fantastically the descendants of ancient Palestinian Hebrews

This reliance of antisemites and Zionists on the separateness of the Jews as a "race" proved catastrophic to the lives of millions of European Jews who perished in Hitler's genocidal camps and triumphant (if catastrophic to the Palestinian people) to those Jews who became armed colonists in Palestine.

The Zionists continued to insist on Jewish racialism. Indeed, in the last few decades, they have been fanatical enthusiasts in welcoming the questionable conclusions of some geneticists about the so-called "Jewish gene".

Ever since the coding of the human genome, the new discovery has led to all kinds of commercial ventures that claim to tell people which "race" they allegedly belong to according to their "genes," even when many scientists believe that the very notion of "race" does not even exist as a scientific biological category.

Scholars, especially historians of science, have been meticulous critics of the suspect methodologies employed by geneticists to interpret genetic data. The prominent geneticist Richard Lewontin, for one, was tireless in exposing these questionable methods, as many others have been, especially when it came to the "scientific" search for the "Jewish gene".

Nonetheless, Zionism insists, as it had since the beginning of the 20th century, that Jews from every part of the world belong to one race and are one people. Zionists deployed this originally antisemitic claim to argue that modern European Jews are somehow rooted in Palestine in order to render them fantastically the descendants of ancient Palestinian Hebrews.

Yet, in one rare instance, two major Zionist leaders, David Ben Gurion and Yitzhak Ben Zvi, argued in a 1918 book that it was Palestinian peasants - then the majority of the Palestinian population - who were in fact the descendants of the ancient Hebrews, a claim that has been buried since.

Returning to Haifa

Palestinian intellectuals, however, were never convinced by Zionism's racialist arguments. Ghassan Kanafani took up the challenge in his 1969 novel Returning to Haifa and published a devastating riposte to the Zionists.

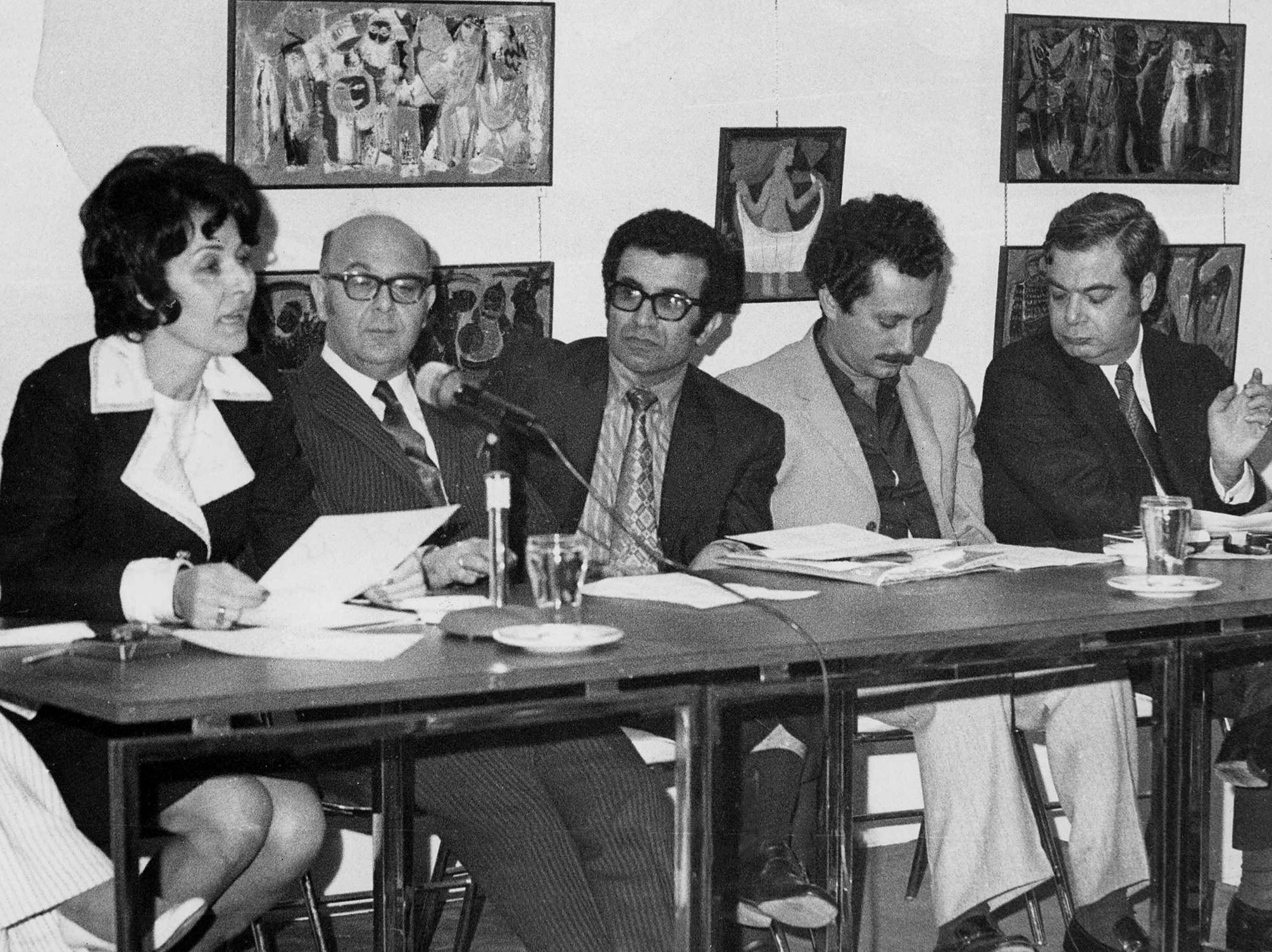

Kanafani's intellectual, literary, and political legacy persists 50 years after his assassination in an Israeli-planted car bomb at the age of 36 with his 18-year-old niece in Beirut on 8 July 1972.

Returning to Haifa is a brilliant and shattering refutation of Zionist biologism, where Kanafani insists that principles and a commitment to justice are what define a human being and not biology and blood, nor geographic origins or paternal or maternal descent.

For Kanafani, Palestinians are to be defined by their principles in contrast to racialism with which Zionism defines Jews. It is one equation that Kanafani conjures that overturns geography and biology, namely: "al-insan qadiyyah," or a human being is a cause and a set of principles, and humans must be judged in accordance with those principles that make them who they are.

When Sa'id and his wife Safiyya, 1948 refugees living in the West Bank, return to Haifa after the 1967 occupation to recover their lost child, who had remained in their house in the panic and pandemonium of the expulsion during the 1948 Nakba, what they found there transformed them at the core.

Their house and all its contents had been stolen by Zionist settlers and given to Polish Jewish colonists, Ephrat and Miriam Kochen, who were brought to colonise Palestine by the Jewish Agency.

The Zionists find the Palestinian toddler left alone in the house and grant him to the Kochens, who abduct/adopt him. Miriam's father, the novella reveals, had been killed in Auschwitz, while her brother was shot dead by the Nazis. Her husband Ephrat, like many Holocaust survivors, had joined the Israeli army. He was killed in the 1956 Israeli invasion of Egypt.

In providing the tragic background history of Jewish colonists, Kanafani humanises the conquerors of Palestine.

When Miriam, for example, witnessed a dead and bloodied Palestinian child being thrown by two Zionist soldiers into the back of a truck, she knew he was not Jewish by the way he was discarded, and was reminded of the fate of her brother and other Jewish children killed during World War II.

Thus, Jews who had no political, racial, or military ideology of conquest in Europe were victims of those European Christians who did, while Jews who had a colonial ideology and racialised colonial power in Palestine victimised the Palestinians.

Here Kanafani is pointing to the question of ideology and power, and not biological or racial identity, as that which determines the fate of a people.

Ideology as identity

Once Sa'id and Safiyyah realise that their firstborn son Khaldun (meaning "the immortal one") had been abducted by the Jewish couple who stole their home and who transformed Khaldun into a Jewish child, renaming him Dov (or "bear"), they begin slowly but surely to understand that Khaldun/Dov was no longer their son and that he had been lost to them forever.

Miriam tells us that Dov looks exactly like Sa'id, but his habits are those of his abductor/adopter father Ephrat. Dov was named not in line with European Jewish tradition, after Jewish prophets, but in line with Zionist ideology, after a predatory animal.

He is now serving in the Israeli army and refers to the Palestinians as "the other side". Upon meeting his defeated Palestinian parents, Dov rejects them outright with much contempt.

Sa'id and Safiyya quickly realise that Khaldun, the immortal one, turned out to be mortal after all, and that he had indeed died in 1948 when Palestine fell and was subsequently reincarnated as a predatory colonial Jew.

It is at this moment that Sa'id wonders out loud: "What is a homeland? Is it these two chairs that remained in this room for twenty years? The table? The peacock feathers? The photograph of Jerusalem hanging on the wall?... Khaldun? Our illusions about him? Paternity? Filiality? What is a homeland?... I am simply asking."

For Kanafani, Palestinians are to be defined by their principles, in contrast to racialism with which Zionism defines Jews

The central question Kanafani's novel poses is that of origins. Are human beings to be defined according to who their parents are, their race and blood, their geographic origins, or by some other criteria? Kanafani's questioning of biological descent as determinant of one's identity is his questioning of what academic theorists call "essentialism".

As some indigenous Palestinians, in the context of the novella, can become colonising Jews and kill other Palestinians, and oppressed European Jews can become oppressors and conquerors of the Palestinians, are biological origins, genes, and geography then what is relevant in determining identity or is it ideology and power?

Kanafani's conclusion is far reaching in its scope. He has Sa'id ask "What is a homeland?" and then concludes that "A human being is a cause and not flesh and blood that he inherits across generations".

For Kanafani, it is here that the Palestinian is transformed from someone who is an original native of Palestine, or one who is biologically determined through birth to Palestinian parents, into someone who is a holder of liberatory and just principles that are contained within and constitute the word "cause" or "qadiyyah".

An optimistic message

The struggle between Palestinians and the European Jewish usurpers of their land, it turns out, was not, despite the insistence of the Zionists, about origins, biological or geographical, after all - since Palestine could become Israel with the stroke of a pen, and a Palestinian son could become a European Jewish one - but rather about ethical principles and justice.

Kanafani's novel rejects Palestinian nostalgia for an unrecoverable dead past and insists on an achievable living future. Writing his novel after the 1968 victory of the resistance against the Israeli army in the Battle of Karameh, he has Sa'id regret his prior opposition to his second son Khalid - who was born after the Nakba and whose name, a variation on Khaldun, also means "the immortal one" - joining the Palestinian guerrillas.

Sa'id declares to Safiyya: "We made a mistake when we thought the homeland was only the past, for Khalid, the homeland is the future... this is why Khalid wants to carry arms. There are tens of thousands like Khalid who are not halted by the tears men shed while looking in the depth of their defeats for scraps of their shields and broken flowers, but look forward to the future, and in doing so, they correct our mistakes, indeed the mistakes of the entire world... Dov is our shame, but Khalid is our enduring honour."

In this hopeful novella, Kanafani understands that the fascist nature of Zionist racialism should never be replicated by the Palestinians in staking their rightful claim to Palestine.

This is the reason that it is imperative for Kanafani that Khaldun, who represents what was thought to be an immortal past, die once and for all with that past, while Khalid, who represents an immortal future, lives on as the agent of resistance to Zionist colonialism.

Kanafani's optimistic message continues to inspire the Palestinian people today and reverberates inside the living Palestinian resistance.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].