Rabaa massacre and the death of Middle East democracy

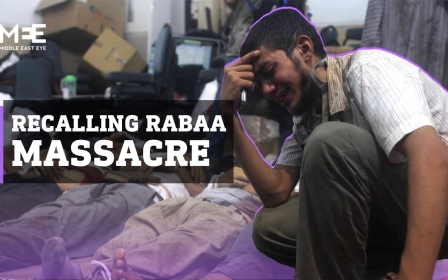

Nine years ago, in the early hours of 14 August 2013, Egyptian security forces descended upon Rabaa Square in Cairo, mounting a vicious assault against pro-democracy activists holding a sit-in to protest against the military coup that had unfolded six weeks earlier.

These events came in the wake of the 2011 popular revolution that had ousted Egypt's geriatric dictator, Hosni Mubarak, who had been in power for three decades. In the two turbulent years that followed, Egypt took halting steps towards democracy, electing a new parliament and president, and establishing a new constitution.

The difference is that the Muslim Brotherhood is enthusiastic about democracy, while Sisi and other dictators resolutely oppose it

Things were far from perfect, but the direction of travel was broadly democratic. The problem for many observers, however, was that these "democrats" came in significant numbers from the Muslim Brotherhood, a democratically oriented Islamic political movement that had gained a plurality in parliament and secured the presidency in 2012.

Likely due to their Islamic rather than liberal background, the Brotherhood was viewed with suspicion from many influential quarters, both within Egypt and beyond its borders. Many Egyptian liberals ultimately backed the 2013 military coup, enabled by the support of counter-revolutionary states in the wider Middle East region, and supported the lethal crackdowns that followed.

The most violent of these took place at Rabaa Square in eastern Cairo, where the most comprehensive study conducted by Human Rights Watch asserted that "likely more than 1,000" protesters were killed by Egyptian security forces.

What is less known is that these crackdowns also had prominent clerical support. In my book Islam and the Arab Revolutions, I undertake a systematic study of the religious debates that took place both in favour of and opposing the revolutions and subsequent coup in Egypt in the early 2010s.

Justifying atrocities

One of Egypt's most prominent religious clerics, Sheikh Ali Gomaa, a scholar who would develop close ties to the Sisi regime, is particularly notorious for his vocal support and justification for the massacres against pro-democracy protesters that took place in the summer of 2013. In the weeks leading up to the Rabaa massacre, which also saw a number of smaller-scale atrocities perpetrated by the security forces, Gomaa offered religious legitimation for the use of force against protesters.

Citing the teachings of the Prophet Muhammad, which have traditionally been understood to justify fighting those engaged in armed rebellion against the state, Gomaa suggested that those who were protesting against Sisi's coup could be killed with religious sanction.

When mass killings ultimately came to pass, Gomaa's response was enthusiastic, as he delivered a celebratory lecture addressing the top brass of the security forces, including Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, and said their actions were supported by God. His most infamous statement from the lecture was his exhortation to soldiers that they could "shoot to kill" protesters.

To this, he would add his reaffirmation of divine support for Egypt's security forces, asserting that "religion is on your side" and "God is on your side".

As Egypt's retired grand mufti and a member of the country's highest clerical body, Gomaa's religious edicts enjoyed wide currency in Egypt. One of his students, Osama al-Azhari, serves as an official religious adviser to Sisi, and Gomaa himself was appointed by Sisi to Egypt's House of Representatives in 2021.

Crucial difference

This reminds us that dictators in the region use religion to prop up their political rule as much as so-called Islamists do. The reality is that dictators like Sisi and his partners throughout the Middle East, including the UAE's Mohammed bin Zayed and Saudi Arabia's Mohammed bin Salman, harness Islam and state-sponsored Islamic scholars to maintain their grip on political power. They are all "Islamists" in this sense.

If Islamism is a commitment to "political Islam" - a commitment to drawing on Islam to justify one's politics - then Sisi, Mohammed bin Zayed and Mohammed bin Salman are all authoritarian Islamists who have perverted the faith to achieve their personal political ambitions.

But there is a crucial difference between the Islamists and their supporters who were massacred by the Egyptian military in 2013, and the Islamists like Sisi and his acolytes in the Egyptian scholarly establishment. The difference is that the Muslim Brotherhood is enthusiastic about democracy, while Sisi and other dictators resolutely oppose it.

Western policymakers must come to terms with the fact that the real fight taking place in the Middle East isn't between Islamists and secularists. It's a fight between authoritarian Islamists and democratic Islamists.

The authoritarian Islamists come in various forms; they can look like the Islamic State group, but they can also look like Sisi. They also reflect similar political values, but democratic Islamists, with all their faults, offer an alternative vision for the Middle East, one that is characterised by political freedom rather than repression.

On this anniversary of the "worst mass unlawful killings" in modern Egyptian history, we would do well to remember the martyrs for freedom and democracy who have been abandoned by western powers unwilling to pay more than lip service to these values - values that are so desperately desired in the Middle East today.

In his 2018 book on the Arab uprisings, New York Times journalist and survivor from inside the Rabaa massacre, David Kirkpatrick, wrote: "Rabaa surpassed the Tiananmen Square massacre in China in 1989." As the West expresses its strong support for Taiwanese democracy in the face of China's sabre-rattling, we should remember the importance of championing democratic struggles everywhere.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].