India: Twitter, Facebook and the appeasement of Hindu extremists

A whistleblower complaint by ex-Twitter security chief Peiter Zatko, revealed last week, includes alarming allegations that the Indian government forced the social media platform to hire government agents who had access to sensitive user data because of Twitter’s weak security structure.

India has the world’s largest number of Facebook users, and its platforms, including WhatsApp, have been deployed by Hindu extremist networks

Twitter, which did not respond to Middle East Eye’s request for comment, has publicly rejected Zatko’s complaint as a "false narrative", but has yet to explicitly address the allegations about the hiring of Indian government agents.

While Zatko’s allegations have not yet been verified, the reference to "government agents could be related to the draconian internet regulations enacted by the Indian government in February 2021.

These rules - triggered partly by Twitter’s clash with New Delhi over demands that it remove accounts in support of anti-government protesters - require large social media companies to employ Indian citizens in three government-mandated positions, including a law enforcement liaison.

The new rules make one of those officials - the chief compliance officer - criminally liable if he or she, for example, does not follow a court order to identify the “first originator” of messages that undermine the “sovereignty” of the Indian state.

That these employees must be Indian citizens who physically reside in the country and face the possibility of arrest is why critics have dubbed such rules "hostage-taking laws". They compel local employees to partake in the censorship of voices hostile to those in power.

But Zatko’s allegations go beyond the very public attempts at censorship by India, which led the world in internet shutdowns in 2020. India’s Hindu nationalist government has been clamping down on public expression, especially by Muslim minorities and dissident voices.

Surveilling dissidents

In recent years, India has intensified the use of colonial-era sedition laws and newer counterterrorism powers to charge or arrest activists and journalists, such as Asif Sultan, Fahad Shah and Masrat Zahra. The allegations made by Zatko raise serious questions about whether New Delhi has inside access within Twitter - and potentially other social media platforms - through these mandated officers or other employees, enabling the surveillance of dissidents in India and Kashmir, as well as critics abroad.

If that is indeed the case, and if the Indian government has access to sensitive user data such as phone numbers, IP addresses and direct messages, it could use Twitter as a surveillance tool to target dissidents and other vulnerable groups.

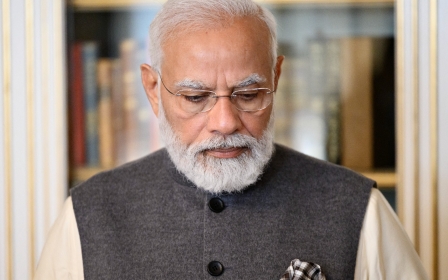

For foreign companies seeking access to India’s massive consumer market, appeasement of the country’s Hindu nationalist networks is now part of the cost of doing business. While Twitter has pushed back against many of New Delhi’s demands, Facebook has been more brazen, with some of its staff allegedly colluding with Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government long before the 2021 internet rules.

In 2020, a Wall Street Journal investigation revealed that Facebook executives in India rejected banning Hindu nationalist politicians who use the platform to make explicit calls for violence, fearing that it would jeopardise the company’s business prospects. India has the world’s largest number of Facebook users, and its platforms, including WhatsApp, have been deployed by Hindu nationalist extremist networks for mob violence.

But it’s not just tech companies that are choosing to indulge toxic political forces in India. During Modi’s 2019 visit to the US, Walmart co-sponsored a rally he held with then-President Donald Trump in Houston, Texas. The event was organised by a group with links to the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), an extremist organisation affiliated with Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). The RSS has lobbied against allowing foreign direct investment in India’s retail sector, seeking to protect small retailers.

Currying favour

India has a long history of overregulation and protectionism. But since Modi’s election in 2014, foreign companies eager to reach India’s enormous middle class have sought to cut through red tape by currying favour with Hindu nationalist networks actively involved in violence.

India is also a country where the idealism of western governments goes to die. They promote democracy and human rights elsewhere, but in India, they covet partnerships with violent Hindu nationalist groups, where the power lies.

Enhancing trade access is a factor, as is selling weapons. India has been the world’s largest importer of arms since 2012, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. But ultimately, it’s about containing China, which the US sees as its principal strategic rival this century.

The consensus among the US strategic community is that India is vital to this effort. While a shared rivalry with China ultimately drives the US-India strategic partnership, Washington colours it in ideological terms - as liberal democracies defending the free world.

India’s constitution identifies the country as secular, and its ability to regularly conduct free and fair elections since independence is a post-colonial success story. But India’s Hindu nationalist government aims to dismantle the very secular constitution whose legacy it benefits from - and it has succeeded to a large extent.

India’s (albeit imperfect) democracy has devolved into “competitive authoritarianism”. Its elections remain credible. But when it comes to censorship, disinformation and religious freedom, India increasingly resembles China and Russia.

Retreat of democracy

India has arguably become the largest purveyor of fake news, with state-linked networks that rival or exceed those of Russia in scale. And the Hindutva ideology espoused by the BJP and RSS calls for the forcible assimilation of Christians and Muslims. Like the Communist Party of China, India’s Hindu nationalists seek to erase markers of Muslim distinctiveness from the public sphere.

Hindu extremists destroyed the 16th-century Babri Mosque and are building a Hindu temple in its place. Calls have been made to do the same to other sites, including the Taj Mahal, an Islamic mausoleum.

Foreign entities that claim to stand up for universal values end up compromising on them in India

India is a glaring example of the spread of digital authoritarianism, the retreat of democracy, and the rise of leaders with a cult of personality - the very global issues that feature in the foreign policy discourse found in Washington. And yet, India is left out of congressional hearings or think-tank studies on these topics.

New Delhi also avoids official censure in Washington on growing threats to religious freedom. And it remains closely allied with Russia, ramping up oil imports from Moscow this year.

Because of its perceived geopolitical importance and the size of its consumer market, India avoids the treatment that a country like China or Russia would get. The grim reality for vulnerable communities in India is this: foreign entities that claim to stand up for universal values end up compromising on them in India, putting their commercial or strategic interests first.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].