Haya Barzaq: Meet the woman documenting Gaza's historical architecture

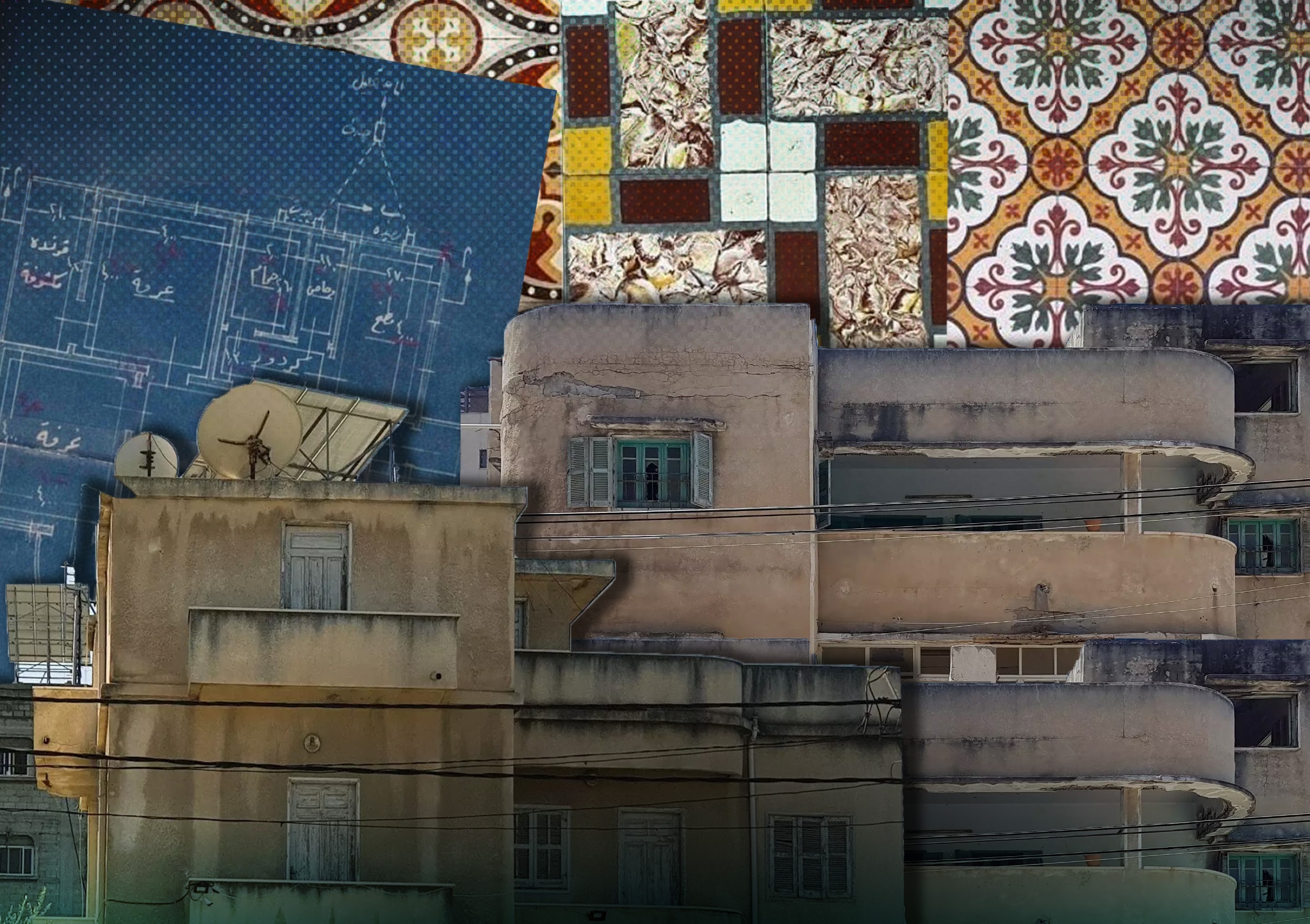

When Haya Barzaq first started taking photos of the distinguished-looking houses and buildings around Gaza, it was simply because she liked the look of them. But as time went on, she began to identify unique features and recurring patterns in the buildings.

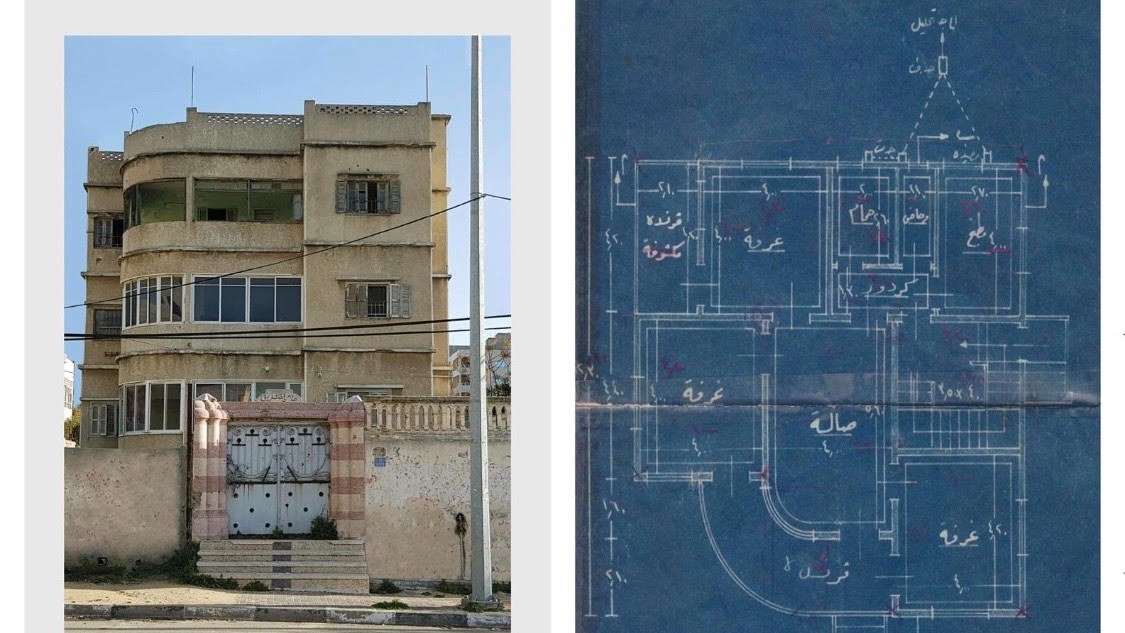

Some had rounded balconies and outdoor living spaces, which Barzaq later traced back to the modernist Bauhaus architecture revolution that started in Germany in the early 20th century. Others were built in the typical Mamluk style.

'I want to document all of these buildings before it is too late'

- Haya Barzaq, engineer

Barzaq, an engineer who also studied architecture at the Islamic University of Gaza, fell in love with the historical buildings around Gaza, and started an initiative which allowed her to document how buildings evolved over time, as well as the historical periods when they were built.

One of the biggest inspirations that compelled her to rapidly document and archive these buildings was the threat posed by Israeli occupation. In May 2021, Israel's offensive on Gaza resulted in the demolition of a significant number of buildings, including residential blocks and medical centres.

“I want to document all of these buildings before it is too late,” she told Middle East Eye. “I aim to make reference to how Gaza’s architecture has developed through the political eras it has been through over the last 50 years.”

German influence

Initially, Barzaq was taking photos of buildings sporadically and sharing them to her Instagram account, but she soon decided it was important to document the buildings in a more strategic manner.

She began reaching out to their owners to find out more about them. From lengthy conversations, she found out that some of the houses were built by contractors who had been to Jaffa and Alexandria, Egypt. One of the common styles she encountered was Bauhaus, as many architects had come into contact with the form during their travels abroad.

Bauhaus, which literally means “construction house”, is a German school of arts that was founded in 1919 by the German-American architect Walter Gropius. Many Jewish-German architects who fled the Nazis to the British Mandate of Palestine are believed to be the reason why hundreds of Bauhaus houses are found in Palestine.

“Most of these houses are located in the modern neighbourhoods in Gaza that first became residential in the 1960s and 70s,” she explained.

Some of the buildings she found around Gaza are from the Byzantine period, including the Byzantine Church, located in the northern Gaza strip, which dates back to the fifth century.

The church, which was recently inaugurated by the Palestinian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities, is believed to have been established around 1,700 years ago. Archaeologists working on the site found graves of emperors and previous worshippers, and examined their bones.

According to experts, the church had a strategic proximity to a location that facilitated ancient trade routes linking Gaza with the Levant and allowed Christian pilgrims easy travel to the Holy Land.

The building comprises a church, chapel and baptistery, and covers around 800 square metres of land. And although it has stood for centuries, the mosaics covering the floors can still be seen. At the start of this year, the building was renovated and opened its doors to the public as a museum.

In the heart of Gaza is the Saint Hilarion site, also known as Tell Umm Amer, which dates back to the fourth century. This ancient Christian monastery is one of the largest in the region, and was uncovered by archaeologists in 1999 after being covered and hidden by an earthquake in 614.

The building, which is located close to Deir al-Balah, is made up of a church complex, chapel, several basements, a bath house, monk’s residence, and a courtyard. Although Palestinians state that Israel has stolen nearly 60 percent of the site's antiquities, the site is listed by Unesco as part of its World Heritage List.

Barzaq has even found examples of architecture from the Mamluk period still evident across Gaza, notably Al-Pasha palace, also known as Qasr al-Basha, which is located in the Old City. This building was a key location for the Mamluks in the 13th century, and features quintessential examples of architecture from that period, including geometric patterns, domes and cross-vault designs.

Historical buildings under threat

After developing a relationship with the owners of the homes she saw around Gaza, Barzaq was granted access into some, allowing her to explore the designs of the rooms.

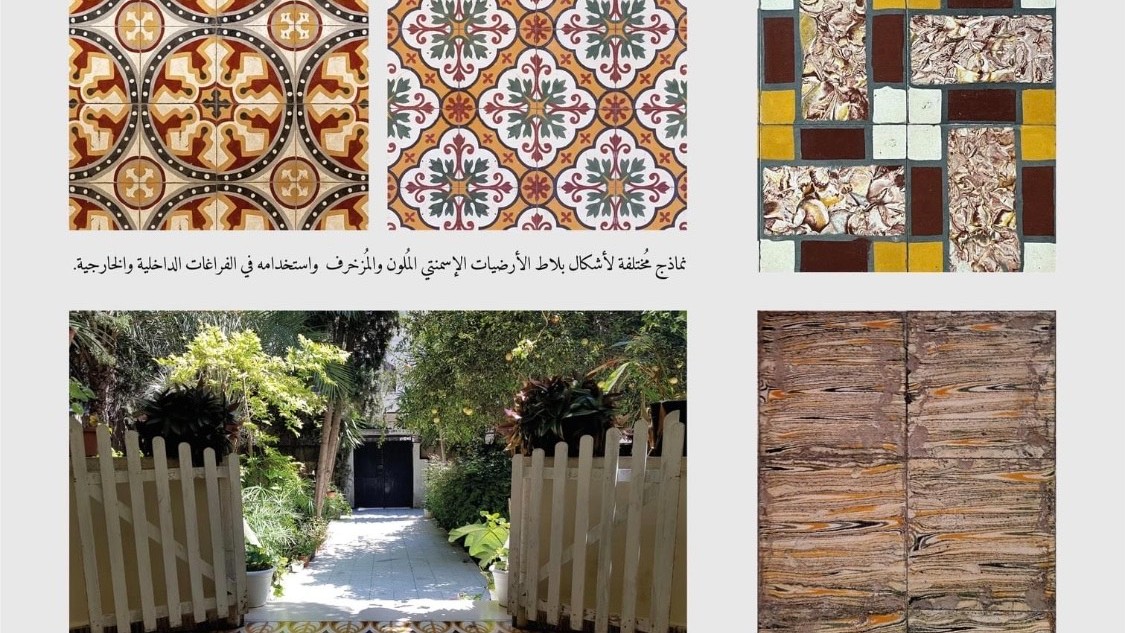

“I was amazed by the details of these houses; many of them had painted floors, handmade iron handrails, and other interesting details. It sometimes felt like I was in a museum and not in a house,” she said.

Despite Barzaq’s passion for Gaza’s historical architecture, she believes greater emphasis should also be placed on contemporary buildings, stating that they are no less important than ancient heritage.

Today, Gaza is home mainly to tall residential buildings, which have sprung up in the past 20 years in a bid to cater to the high population in what is often described as one of the world’s most crowded enclaves. The residential apartment blocks are typically around 20 storeys high, with each floor having around two or three apartments.

Barzaq says one of her biggest concerns is the demolition threats against Gaza's historic homes and buildings. Many homes around Gaza have been abandoned after their owners were forced to flee following Israel’s offensive in May 2021.

Barzaq says that many are set to be flattened or replaced with new, larger residential blocks.

Barzaq hopes to continue documenting these historic homes by developing an archive. She recently participated in a workshop designed to inform the local community about these homes and raise awareness about the unique architecture in the city.

Some of these workshops are organised by local cultural centres, such as the AM Qattan foundation in Ramallah, a non-profit organisation focused on supporting culture and education.

Barzaq’s work has been praised online, with many people sharing photos of her archiving efforts and thanking her for shedding light on Gaza’s architectural legacy.

While the increasing population means that the majority of new buildings are getting bigger, and all tend to look the same, Barzaq maintains that this is not the real Gaza, and there are many examples of authentic and beautiful architecture.

“My job is to explore these beautiful buildings and show them off to the rest of the world,” she says. “I saw that people liked the idea and wanted to know more about architecture in Gaza, so they were really encouraging of what I do.”

For now, she is focusing her efforts on her next archive, and continuing to explore new parts of Gaza and the hidden architecture it has to offer.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].