Qatar World Cup: Football, neoliberalism and revolution in the Middle East

Far and away the most popular sport in the world, football has a special place in the states and societies of the Middle East.

The beautiful game has a rich and vibrant history in the region and continues to be the single most unifying cultural force in the realm of sports. Football brings together families as they pass down their support for clubs from one generation to the next. The sport brings cities out in full force to celebrate their local team’s most memorable victories. It mobilises entire nations beneath the badge of their country on football’s largest stage: the Federation Internationale de Football Association (Fifa) World Cup.

Football fandom has also been channelled in the course of popular revolutions, while authoritarian rulers have relied on it to bolster support for their regimes. It has been invoked in the relations between states, both in times of cooperation and in times of conflict. As the brief sketches below demonstrate, the story of football in the Middle East is inseparable from the broader experiences of the region and the destinies of its people.

The story of football in the Middle East is inseparable from the broader experiences of the region and the destinies of its people

Against all odds, the Iraqi national football team defeated the likes of Australia and South Korea to reach the 2007 final of the Asian Cup, where it faced perennial favourite and three-time winners of the tournament, Saudi Arabia.

Even under ideal conditions, reaching a first-ever final would be an impressive feat for Iraq, but at this moment, the cup final line-up represented what one writer observed as “the side without a country, against the most well-funded national side in the world”.

Since the 2003 invasion of Iraq by the United States, which followed more than a decade of debilitating economic sanctions, the Iraqi national team had faced perilous conditions that tempered any footballing ambitions the country may have held. In the leadup to the tournament, the team was forced to train in neighbouring Jordan to escape the ravages of military occupation and sectarian violence back home. Then, on the eve of the opening group stage match, the team’s physiotherapist was killed by a car bomb in Baghdad while attempting to rejoin the squad.

The Iraq team lifted the cup in Jakarta, following a narrow 1–0 win over Saudi Arabia in the final. The victory, however, had been overshadowed by the news from home, as a series of bombings killed 50 Iraqi fans while they celebrated their team’s semi-final win over South Korea.

Subsequent news reports juxtaposed the team’s remarkable achievement with the adversity it faced. The blending of the two produced narratives about the unity displayed “across Iraq’s sectarian divide” and “the healing power of sport”.

'Eradicating misconceptions'

Three years later, in 2010, world football’s governing body, Fifa, would declare that it had accepted Qatar’s bid to host the 2022 World Cup. The announcement was at once met with jubilation and incredulity. Qatar would become the smallest country to ever host a World Cup and the first in the Middle East to do so.

Buoyed by the country’s natural gas wealth, Qatar’s leaders positioned their nation as a technically advanced site to host a tournament that “created new concepts” and “pushed the boundaries”, while also pledging to be more inclusive than conventional tournaments - “a World Cup for everyone”, according to the chairman of the Qatar bid, Sheikh Mohammed bin Hamad Al Thani.

Sheikha Moza bint Nasser, the wife of the country’s ruling emir at the time, added: “This is an opportunity to eradicate misconceptions, not just about Qatar, but about the wider Islamic and Arab world.”

Elsewhere, Fifa’s announcement elicited considerable outcry. Critics questioned every facet of the decision, from Qatar’s lack of a strong footballing pedigree, to concerns over climate conditions during the desert country’s intensely hot summer months (in which the games are traditionally played).

Others expressed scepticism toward Qatar’s ability to pull off the logistical feat of constructing new stadiums, training facilities, hotels and a public transit system, among other infrastructure requirements, even with the tournament being 12 years away.

Cultural arguments advanced the notion that a Muslim country that limited the sale of alcohol could not possibly host a global event in which alcohol consumption was a central feature of the fan experience. Some questioned the integrity of the process itself, in which “an unlikely nation” was awarded the World Cup, amid allegations of vote-buying and corruption within Fifa.

Most of all, however, Qatar would face intense scrutiny over the conditions of its migrant labour force, which formed the backbone of the country’s ability to build the infrastructure vital to the delivery of the tournament. In light of persistent accusations that it was practising “modern-day slavery”, Qatar faced intense pressure to reform its labour system to bring it in line with international human rights standards.

Egypt's ultras

Only a few months after Qatar’s successful World Cup bid made headlines, a wave of popular uprisings swept the Middle East and North Africa. As one authoritarian regime after another faced the prospect of being overthrown in favour of a more representative political order, observers shifted their focus to examining the various social movements that mobilised in opposition to deeply entrenched dictatorships.

In Egypt, which saw the three-decade rule of Hosni Mubarak upended by an 18-day mass protest, the role of football ultras (hardcore fans) was noted for defending protesters confronted by state violence. In their storied past, devoted fan groups such as the Al-Ahlawy Ultras (of Al-Ahly Sporting Club) were no strangers to repressive crackdowns.

As one member of Al-Ahlawy recounted: “It wasn’t just supporting a team; you were fighting a system and the country as a whole. We were fighting the police, fighting the government, fighting for our rights.”

That experience proved valuable when Mubarak sent both police forces and plain-clothed gangs to disperse the protesters at Tahrir Square in Cairo and elsewhere across the country. The ultras repelled attacks by government forces, protected civilian protesters, and maintained the pressure on the regime that ultimately led to Mubarak’s removal.

In the words of one observer, the Port Said tragedy 'transformed a football fan club of revolutionaries into a political entity'

During the transitional period that followed, the ultras continued to be a fixture at the mass protests objecting to the military’s domination of the political process. Then, following a match at Port Said Stadium in February 2012, 74 Al-Ahly supporters were killed in attacks by armed thugs as police stood by and did nothing. The assault was likely premeditated - retribution for the ultras’ anti-regime activism.

The massacre was by far the largest instance of violence in Egyptian football history. In the words of one observer, the Port Said tragedy “transformed a football fan club of revolutionaries into a political entity”. The ultras’ efforts to seek justice for the victims through Egyptian courts were denied. Instead, the government issued a ban on all fans in football stadiums, which was only partially lifted in 2018.

As for the ultras, the revived authoritarian regime led by President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi outlawed all organised fan groups as part of its broader efforts to suppress independent political currents within Egyptian society.

Football's universality and permeability

In the shadow of these and other developments, it is no surprise that over the course of the past decade, football in the Middle East has emerged as the subject of both impassioned political and cultural expression as well as academic study.

Historian Rashid Khalidi identified the problems in defining the “Middle East” as a self-contained unit of analysis, owing to the lack of precision in determining its physical boundaries, the colonial origins of the term, and its continued political uses in the service of neo-imperial interests.

He also noted the failure to account for economic, social and political processes that transcend regional confines, and called upon scholars to seek the connective tissue between phenomena with roots in the region and their manifestations beyond narrowly defined geographies.

There are few developments in the modern era that rise to this call more than football, a sport that originated elsewhere and has captured the imaginations of populations across all continents, but nevertheless developed deep political, cultural and social roots in the Middle East.

The studies presented here reflect an understanding of the region as a porous unit of analysis with processes that can be traced to regions beyond, observed in part through the universality and permeability that football offers.

This volume aims to build upon the recent surge in interest in football as the leading sport in the Middle East, while also highlighting its longstanding presence as a political and cultural force for over a century.

To be sure, the beautiful game has roots in the region that date back to the era of European colonial rule, state-building and modernisation. The introduction of football as a leisure activity and an organised sport was part and parcel of broader efforts by officials to transform colonised subjects into “properly obedient individuals” whose physical conditioning formed an integral part of colonial education. Local elites internalised discourses on organised sports as a mark of cultural and civilisational advancement.

Egyptian nationalists believed their country’s participation in the 1920 and 1924 Olympic Games represented Egypt’s arrival as a fully fledged member of the global community of nations. In Mandate Palestine, organised football matches were alternately used by colonial officials “to pacify the anger of the Arab population who opposed the pro-Zionist British policy", as well as by Zionist settlers and indigenous Palestinians to assert competing nationalist claims.

The establishment of an annual football tournament in the mid-1940s aided the Hashemite monarchy in its consolidation of Jordanian national identity, while in Sudan, college graduates’ assumption of leadership in the national football association represented “an early exercise in mass politics and popular government”.

Football as 'distraction'

As scholars have noted, football’s central place in public life across the Middle East and North Africa continued well into the era of anti-colonial revolution and radical politics. As part of its revolutionary struggle against France, the Front de Liberation Nationale (FLN) assembled a football team to advocate on behalf of Algerian independence while competing internationally.

Upon leading the military’s overthrow of the Egyptian monarchy, Gamal Abdel Nasser went to great lengths to enlist the Egyptian Football Association in mobilising mass support for the newly established republic, using it to empower the armed forces and legitimise the dominant role it came to play in governance.

'Football as peacemaking' became a frequent refrain, with the United Nations establishing a series of programmes promoting football as a tool for conflict resolution

So, too, was football considered a liability to more pressing political demands. In the aftermath of Egypt’s defeat in the June 1967 war with Israel, Nasser suspended the Egyptian league, labelling it a “distraction” from the goal of national liberation.

Similarly, in the lead-up to the 1979 Iranian revolution, opponents of the ruling monarch argued that the national obsession with football represented a deliberate attempt by the Pahlavi regime to subdue the population into quiet obedience in the face of government corruption and repression.

By the late 1990s, amid emerging discourses on the impact of globalisation on local societies, football was frequently invoked as a device to understand international relations, neoliberal economics and the homogenisation of popular culture. “Football as peacemaking” became a frequent refrain, with the United Nations establishing a series of programmes promoting football as a tool for conflict resolution and economic development.

'Football revolution'

More than just another game, the group stage match between the United States and Iran at the 1998 World Cup carried the weight of nearly 20 years of hostile relations between the two states. The drama surrounding the match, which Iran won 2–1, played out in the realm of global public opinion and in conciliatory statements by the heads of state of both nations.

Emboldened by the perceived political opening posed by the globalisation of football, one prominent writer envisaged a “football revolution” in the Middle East that would displace the forces of political Islam and anti-Americanism.

Furthermore, the acquisition of a number of high-profile European clubs by multinational corporate conglomerates, coupled with the increased commodification of football on a global scale, saw the Middle East develop into one of the most promising consumer markets for the sport in the 21st century. Some critics warned that the market-driven and individualistic nature of neoliberalism would pose a direct threat to the “collectivist values” historically embedded in football competition and fandom.

Alternatively, these scholars appealed to the notion of “glocalisation” as an interpretive tool that would at once highlight how globalisation is marked by trends towards both commonality or uniformity and divergence and differentiation.

These interdependencies are more fully captured by the broad opposition between “homogenisation” and “heterogenisation”, which registers trends towards cultural convergence and divergence.

To pick the most elementary illustration, while football’s global diffusion points towards a worldwide convergence over the popularity of particular sports, many societies display divergence in how they organise, interpret and play the game.

In contrast to the more expectant voices that positioned the sport as a transformative force within society, this approach seeks to underscore football’s centrality as part and parcel of broader social phenomena.

Put another way, “in the realms of politics and economics, it is easier to see how [football] reflects political and economic globalisation more than it contributes to them”. This point rings true in the various developments that followed, particularly when charting the recent evolution of football in the Middle East.

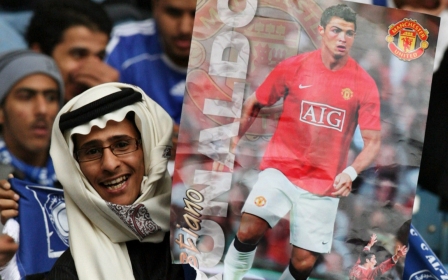

Beginning with the 2008 purchase of Manchester City FC by an Emirati royal investment group, Gulf states would flex their economic muscle in the realm of world football, reviving the competitive fortunes of a number of European clubs in the process.

Heated rivalries between national football teams and their supporters represented broader political conflicts between states and the cynical attempts by authoritarian rulers to deflect attention from their own failures, as occurred in 2009 when Egypt and Algeria battled for one of the final spots in the following year’s World Cup. The qualification matches sparked hypernationalistic rhetoric by media and state officials in both countries, and saw an outbreak of violence among fans.

Indeed, the experiences of football fans in the Middle East have frequently offered a reflection of the political and socioeconomic realities of the states in the region, from their mobilisation against authoritarian rule, to their efforts to challenge economic corruption and gender discrimination.

The above sentiment is equally apparent in the campaign to host the 2022 World Cup in Qatar, a $200bn endeavour that reflects less upon the sporting ambitions of a country than its leveraging of unrivalled economic standing to advance critical national interests.

This is an extract from Football in the Middle East: State, Society, and the Beautiful Game, edited by Abdullah Al-Arian and published by Hurst/Oxford University Press.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].