Turkey elections: Why the CHP has changed its stance on headscarves

The controversy over headscarves has fuelled a major political and social crisis in Turkey. Last week, the main opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP) took a huge step towards providing constitutional guarantees for women wearing the hijab, as the debate over secularism again rose to the surface.

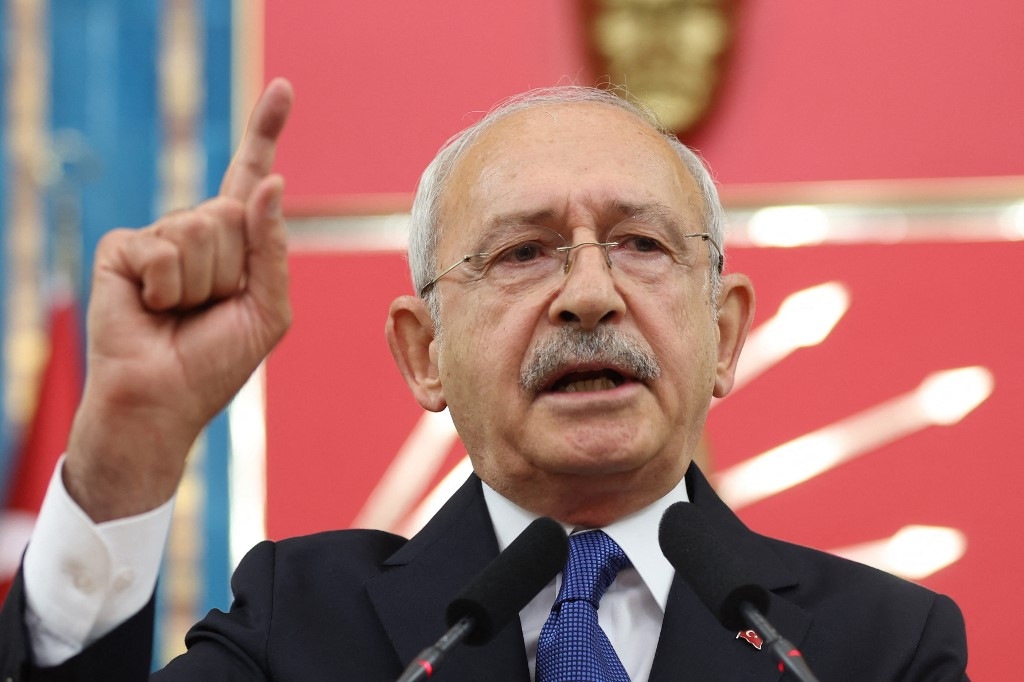

CHP leader Kemal Kilicdaroglu recently shared a video on Twitter to announce the submission of a draft bill that would guarantee women the right to wear headscarves while working in public institutions. The move harkens back to Kilicdaroglu’s previous push for “helallesme”, or reconciliation, a reference to making amends for past wrongs and seeking peace within society.

This new era has incorporated not only the evolution of the idea of secularism, but also the evolution of political parties

But his attempt to resolve this chronic problem over religious attire has sparked public confusion, since the CHP once supported a ban on headscarves - a position fuelled by the party’s aggressive secularism. So what led to the turnaround on this issue?

Kemalism, the founding ideology of the Turkish Republic, outlines six fundamental principles, one of which is secularism. These principles are symbolised as six arrows on the CHP’s flag. According to the Turkish Constitution, “sacred religious feelings” should not be involved in state affairs.

But beyond its longstanding impacts on the country’s affairs, secularism has been used as a tool to regulate people’s lives in Turkey, including their religious lives.

Consequences of secularism

In the early republican days, the Kemalist ideology took crucial steps towards spreading a secular lifestyle, accepted as a precondition for escaping the Ottoman fate. This had severe consequences, particularly in the field of education, where women wearing headscarves were banned from public universities.

President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP) came to power in 2002, but it could not immediately solve the headscarf issue, despite its efforts to soften the notion of secularism. During the AKP’s first term, memories of the 1997 coup were fresh, after a legitimately elected government was deposed because of the aggressive secularism of the army and politicians, along with many academics, journalists and businesspeople.

The opposition used secular ideology as a tool against the AKP during its first decade in power. Erdogan and other party members were threatened with removal, amid allegations that the party had “become the centre of activities contrary to the principle of secularism”. Secularism thus became a tool to justify the opposition’s criticisms of the government.

In 2007, the Turkish army published an online memorandum to display the military’s “sensitivity over secularism”. The following year, Turkey’s top court was asked to shut down the governing party on charges that it was pushing for Islamic law, allegations the AKP denied. Abdullah Gul, the former president, has also been the target of criticism over his wife’s headscarf.

Evolving positions

In 2013, the government lifted Turkey’s decades-long ban on wearing the headscarf in the civil service (a move applied by some public institutions several years earlier). Through such actions, Erdogan’s party positioned itself as the country’s primary challenger to the headscarf problem, leading to an enduring shift in Turkey’s secular ideology.

The CHP could not resist this shift, and eventually transformed its political stance. This new era, dubbed by some “post-Kemalist Turkey”, has incorporated not only the evolution of the idea of secularism, but also the evolution of political parties. Hints of this were seen as early as 2008, when the CHP allowed women wearing headscarves to become members. In 2020, a woman wearing a headscarf was elected to the party assembly for the first time.

Also in recent years, two former members of the Islamist Felicity Party, Mehmet Bekaroglu and Cihangir Islam, joined the CHP. In 2017, Kilicdaroglu described his party as a “defender of the freedom of religion and conscience” in Turkey. The following year, the CHP formed a coalition that included the Felicity Party. While such developments have not been welcomed by some party members and supporters, Kilicdaroglu has nonetheless forged ahead with this transformation.

Ahead of next year’s presidential election, the opposition bloc aims to enhance its coalition by including groups from across the Islamist, secular, and Turkish and Kurdish nationalist spectrum, coalesced around the possible candidacy of Kilicdaroglu. That is why his discourse aims to be inclusive of these groups - but the CHP’s legacy throughout Turkey’s political history will present a significant obstacle.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].